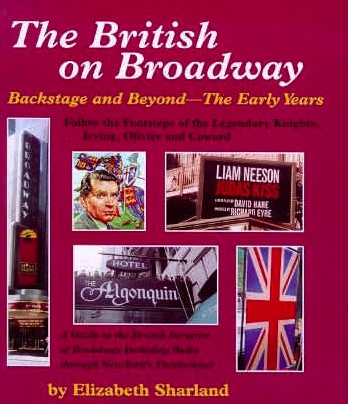

(Book Cover ℅ Barbican Press)

by Michael Elihu Colby

Part 9: The British Are Staying!

To this day, the Algonquin has been so closely associated with British artists, that its marquee was part of the cover of The British on Broadway, a book by Elizabeth Sharland. Devoting a section of her 1999 chronicle to the hotel, Sharland wrote:

The Algonquin Hotel…has been the home to most of the British contingent of actors for over 50 years. What hotel in the world could boast of a guest-list like the Algonquin? — Noel Coward, Gertrude Lawrence, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Bea Lillie, Jonathan Miller, Ian McKellan, Peter Ustinov, David Hare, the Redgraves, Jeremy Irons, Anthony Hopkins, Trevor Nunn, Tom Stoppard, Peter Hall, Angela Lansbury and Diana Rigg.1

Reasons for this affinity are many. Firstly, situated on West 44th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues, the hotel is a short walking distance from most Broadway theatres. Equally appealing has been the hotel’s intimate size, Edwardian décor, and hospitality. It wasn’t just the menu of Dover sole, London Broil, and Yorkshire Pudding. Even when the hotel was in 1940s disrepair, British stars like Laurence Olivier recommended the hotel to friends and colleagues. There’s a droll story about British actor Ralph Richardson, Olivier’s good friend, who stayed there in 1946—just before my grandparents bought the place. Biographer Garry O’Connor wrote how Richardson used his room to practice an old hobby of his, oil painting. Richardson phoned his NY agent requesting him to “send someone round to the hotel to help me hear my lines…and would she mind posing in the nude.” 2

In the 60’s you’d find that newcomer, Peter O’Toole, sitting in the lobby celebrating his big break as “Laurence of Arabia,” after Marlon Brando and Albert Finney rejected the role. Alan Bates flirted with the hotel operator via the switchboard. You’d step into the small elevator face to face with Robert Shaw (Jaws), Donald Pleasance (Halloween), and, in coming years, Judi Dench, Eileen Atkins, Derek Jacobi, and Billie Whitelaw. It was like watching BBC in person.

From 1962-64, cavorting about were the stars of the British import, Beyond the Fringe: Alan Bennett, Jonathan Miller, Peter Cook, and Dudley Moore. Beyond the Fringe was the smash revue starring and co-written by this quartet, catapulting the careers of all four. Alan Bennett became best known as a writer, winning countless awards for such plays as The History Boys—including The New York Drama Critics Award, voted and presented annually at the Algonquin. Jonathan Miller, who was especially friendly with my grandmother, was one of the few people I’ve known whom I’d consider a true Renaissance Man. Originally a practicing physician, the intellectual Miller became an acclaimed British TV personality, humorist, stage director, and sculptor. Even among the esteemed intelligentsia of the Algonquin, the 6’ 4” Miller towered in so many ways.

Dudley Moore and Peter Cook branched off as a famous comedy team. They are best known to Americans through such movies as Bedazzled and The Wrong Box, not to mention films they made separately—especially Moore (classics such as 10 and Arthur). Both actors lived at the Algonquin during their glorious return to Broadway in the 1973 revue Good Evening. That’s when I was privileged to spend time with Moore, who was extremely gracious and generous. My brother Douglas and I met him one day to play songs we’d written for a proposed musical version of Moore’s film The Wrong Box. Since Moore was an acclaimed musician as well as comedian, his chuckling over some of my lyrics was music to a teenager’s ears. On other occasions, I remember noticing how, even though Cook was the tall, distinguished looking one, it was usually Moore who was accompanied by beautiful women. This fact was acknowledged by Barbara Walters in a TV tribute. She declared “despite his height … he had always been a ladies man. Some called him ‘cuddly Duddly.’” 3

Though many Oscar winners stayed at the hotel, there was a preponderance of Britishers who received the “Supporting Actor” award: including Donald Crisp (How Green Was My Valley), Hugh Griffith (Ben Hur), Peter Ustinov (Spartacus and Topkapi), John Mills (Ryan’s Daughter), and John Gielgud (Arthur). Ustinov multi-tasked on Broadway, a consummate actor, director, and/or a playwright—sometimes all three (Photo Finish). Among his famous quips were: “I’m convinced there’s a small room in the attic of the Foreign Office where future diplomats are taught to stammer;” and “The only reason I made a commercial for American Express was to pay for my American Express bill.” 4 Once my Grandmother greeted him at lunchtime in the Oak Room, saying “I’ll be seeing your matinee today of A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum [a revival that actually starred Phil Silvers, not Ustinov].” Ustinov replied, “Oh, you’ll love it! And make sure to visit me backstage afterwards.” Ustinov’s naughty side was again evident when, against the backdrop of the usually staid Algonquin, he discovered a favorite possession was missing from his room. Discreetly he promised a reward to the Algonquin staff for anyone who could locate that lost bag of weed. This is a story that was recently told to me by former bellman Will Sawyer. I doubt my grandparents ever knew of Ustinov’s stash (The closest Grandma Mary ever came to mentioning weed was joking that she’d like her spaghetti with “marijuana sauce”).

The more often I visited my grandparents, the more I became aware of this Who’s Who of English channels. The British contingent bridged countless categories. Novelists such as Anthony Burgess (A Clockwork Orange), Grahame Greene (The Power and the Glory) and Lawrence Durrell (Justine). Movie greats like Julie Christie (Oscar’d for Darling) and Peter Finch (Oscar’d for Network). Stage directors like Peter Brook (Tony’d for Marat-Sade), Peter Hall (Tony’d forThe Homecoming), and John Dexter (Tony’d for Equus and M. Butterfly). For decades, writer Alec Waugh (Island In the Sun) lived part of every year at the Algonquin.5 Making at least one annual trip, too, was Ray Cooney, Britain’s premiere writer of Feydeau-like sex farces, whose Run for Your Wife ran nine years in London’s West End. Playwright John Osborne returned year after year with another imported smash (The Entertainer, Luther, Inadmissible Evidence). Especially impressive, according to bellhop Tony Cichielo, was Osborne’s giving Cichielo the biggest tip he ever got, a $100 bill (back when orchestra tickets sold for nine dollars).6

In addition, during the late 60’s and early 70’s, the Algonquin played host to countless new English playwrights working on Tony winning-shows. These included: Christopher Hampton‘s The Philanthropist, which received 4 nominations; Simon Grey’s Butley (won “Best Actor” for Alan Bates); and David Storey’s The Changing Room (Best Supporting Actor” for John Lithgow). Tom Stoppard topped them all with 4 “Best Play” wins: for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Travesties, The Real Thing, and The Coast of Utopia—each receiving several other Tonys.

At the height of the theatre season, you’d likewise spot British theatre producers—either importing their shows to New York or keeping up with the latest Broadway offerings. Two producers were especially close to my grandparents, serving as reciprocal hosts any time the Bodnes visited London. One was Peter Bridge, an intense producer largely responsible for advancing the career of the prolific playwright Alan Ayckbourn (often called England’s equivalent to Neil Simon). Bridge produced Ayckbourn’s first Broadway show, the British farce How the Other Half Loves, making some difficult choices. One good choice was having Ayckbourn stay at the Algonquin, where he’d later launch many a Broadway triumph (including Absurd Person Singular and The Norman Conquests). A questionable choice was taking a delectably British farce and having Ayckbourn rewrite it as an American comedy—to star Phil Silvers and Sandy Dennis (albeit their presence helped raise the capitalization). 7 The gambit didn’t quite work. The show was like a close-to-ingenious Rube Goldberg construct with one essential part—the distinct British humor—missing.

When How the Other Half Loves opened to mixed reviews and a disappointing run, Peter Bridge took it badly, becoming another example Grandma Mary used to dissuade me from going into the theatre. Bridge’s mood swings were severe: going from Nirvana to near nervous breakdown. Nevertheless, he was a kindly man—passionate about family and theatre—whose young son stayed in his Algonquin suite during visits to New York, including for Bridge’s Broadway hit The Man in the Glass Booth. That son was Andrew Bridge, who grew up to be a 3-time Tony-winner as lighting designer for Phantom of the Opera, Fosse, and Sunset Boulevard. As for Alan Ayckbourn, his future New York hits all retained their original English settings.

My grandparents’ best producer friend was the legendary Harold Fielding. This always jolly and elfin impresario produced new London musicals as well as UK premieres of Broadway classics. He made a stage star out of Tommy Steele, one of Britain’s first big rock and roll idols,8 commissioning the creation of Half a Sixpence—the hit musical which Steele top-lined in London, on Broadway, and in film. Among Fielding’s stellar imports to London were The Music Man (with Van Johnson), Sweet Charity (with Juliet Prowse), Show Boat (with Cleo Laine), Mame (with Ginger Rogers), and Barnum (with Michael Crawford). As reporter Dennis Barker wrote, “His ambition was to make the West End a rival to Broadway as a venue for musicals…with such shows as Charlie Girl, which he launched in 1965 and which ran for 2,202 consecutive performances.” 9

Fielding often visited the Algonquin with an entourage including his taller, rounder, blonde wife Maisie and his assistant Ian Bevan, together looking like they just stepped out of a Charles Dickens novel. When I took my first trips to London, in the company of Grandma Mary and my brother Douglas, it was Fielding who regaled us with dinners and backstage visits to his musicals, Show Boat and later Gone With the Wind. The musical version of Gone With the Wind was a typically lavish Harold Fielding production, complete with muslin wisteria trees, the wounded soldiers/railroad scene, plus antebellum costumes to suit any cotillion. Happily, Harold Fielding allowed Douglas and me an insider’s perspective. I’ll never forget the staged burnng of Atlanta, which Douglas and I watched from the theatre wings. Scarlett (June Ritchie) struggled on-stage with a real horse tied to a wagon, within which—unseen by the audience—the “pregnant” Melanie (Patricia Michael) was applying make-up to look sickly. I never found out if that was the same naughty horse who, on opening night, received much attention by taking the greeting “Merde” too literally. I might have seen the standby (or should I say the “gallop-by”).

Unfortunately, some of the critics also dumped on Gone With the Wind. Though it ran through the year, it was not a success. Still, Fielding was accustomed to the occasional flop, the most costly being a musical about the showman Fielding emulated, Ziegfeld, which lost a then-staggering £1.3 million. But Fielding had developed a thick-skin through far worse experiences. He once flew on a Constellation plane whose roof was crashed into by a smaller plane—whereby the dead pilot fell into Fielding’s lap. Despite the other plane’s wreckage, the Constellation plane made a perfect landing. Having survived such circumstances, Fielding buoyantly believed “flying was the safest form of travel.” 10 I’m particularly grateful Fielding didn’t mention this to my grandmother before she booked our flight to London.

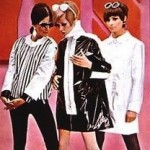

Beyond theatre folk, British fashion icon Mary Quant was another fixture at the hotel. Trailblazing the way for designers like Rudy Gernreich, it was Quant who originated the mini skirt, hot pants, and waterproof mascara.11 She epitomized “Swinging England” as much as Twiggy and the Beatles. Following up, she popularized the micro mini, “paint-box makeup, lace-up boots, and the plastic raincoats that became the rage in the U.S. and England during the 1960s.12 Though never sported by the Bodnes or Colbys, these styles did materialize on some of my more daring female classmates.

Most importantly, Quant showed savvy by making her designs affordable to the average working girl. If that weren’t insightful enough, when asked what she liked best about the United States, she replied “The Algonquin Hotel, corn beef on rye and your telephone system.” I would guess, the sight of Quant’s modish models in the lobby—incongruously flanking such early American movie types as Lillian Gish and Edward Everett Horton—was my nearest experience to a psychedelic acid trip.

The Irish side of the United Kingdom was well represented, too, at the Algonquin. Frequent guests included the great Irish playwright Brian Friel (Dancing at Lugnasa), “doyenne” of Irish literature Edna O’Brien (Saints and Sinners),13 and actor Jack MacGowran (A member of Dublin’s Abbey Players and renowned interpreter of Samuel Beckett plays, MacGowran died at the Algonquin in 1973, right after completing his scenes for the film The Exorcist).

Still, it was the British contingent that most influenced me. To this day, when I’ve worked as a substitute teacher in New Jersey, the students will inquire, “Are you from England?” I reply, “Only by osmosis.” Another related story occurred during the run of my show Charlotte Sweet—a musical set in Victorian England. Charlotte Sweet was launched off-off Broadway as a showcase production, where I had to economize on everything—working as co-producer, janitor, box office attendant, you name it. One night, a distinguished elderly actress (reminding me of Kitty Carlisle) arrived to pick up her ticket. Having no idea who I was, she addressed me at the box office. “Sir,” she politely stated, “I understand they’ve flown the playwright all the way from England for this production. Is that so?” Not wanting to spoil the illusion, I smiled and replied, “How did you ever find out?”

I treasure how the British connection seems to follow me, ever since my days at the Algonquin.

Next part: Musicals “R” Us

1 Sharland, Elizabeth. The British on Broadway: Backstage and Beyond—The Early Years. Lancaster England: Barbican Press, 1999.

2 O’Connor, Gary. Ralph Richardson: An Actor’s Life. New York: Applause Books: March 1, 2001.

3 Walters, Barbara. On 20/20 (ABC-TV), first broadcast November 19, 1999: http://www.pspinformation.com/voices/other/dudley_moore_interview.shtml.

4 Ustinov, Peter. “Quotations by Author” @ http://www.quotationspage.com/quotes/Peter_Ustinov/

5 Edwin McDowell, Alec Waugh obituary in The New York Times, September 4, 1981

6 Uncredited. “Bellhop” from “Talk of the Town” in The New Yorker, September 20, 1993.

7 Murgatroyd, Simon. “How the Other Half Loves: Background” from Alan Ayckbourn’s Official Website, 2014: http://howtheotherhalfloves.alanayckbourn.net/styled/index.html.

8 “Tommy Steele Biography & Filmography” on Matinee Classics LLC © 2014: http://matineeclassics.com/celebrities/actors/tommy_steele/details/

9 Barker, Dennis, Harold Fielding obituary in The Guardian, September 30, 2003.

http://matineeclassics.com/celebrities/actors/tommy_steele/details/

10 “Harold Fielding Biography” on AllMusic Website; http://www.allmusic.com/artist/harold-fielding-mn0000995528/biography © 2014.

11 Moir, Jan. “Still swinging at 77! Mary Quant put the swing into the 60s, gave us that iconic bob cut and – hallelujah! – invented waterproof mascara” from Mail Online. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2096184/Mary-Quant-swing-60s-gave-iconic-bob-cut–hallelujah–invented-waterproof-mascara.html. February 3, 2012.

12 “Mary Quant biography.” Bio.: http://www.thebiographychannel.co.uk/biographies/mary-quant.html. 2011.

13 Cooke, Rachel. “Edna O’Brien: ‘A writer’s imaginative life commences in childhood’” from The Guardian / The Observer: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/feb/06/edna-obrien-ireland-interview. February 5, 20011.

© 2014, Michael Colby

*No copyright Infringement Intended. For Entertainment Purposes Only.

Click Below for Parts 1 thru 8 :

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/algonquin-kid-part-way-back/

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/algonquin-kid-part-2-algonquin-renaissance/

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/algonquin-kid-part-3-series/

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/algonquin-kid-part-4-series/

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/algonquin-kid-part-5-series/

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/algonquin-kid-part-6-series/

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/algonquin-kid-part-7-mazel-tov-robert-f-kennedy/

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/algonquin-kid-continues-part-8-series/