Review by JK Clarke

If one were forced to choose a single word to describe Thomas Cromwell, King Henry VIII of England’s secretary, it would have to be consiglière. In popular culture, he most closely resembles the fictitious Tom Hagen, the Corleone family lawyer in The Godfather saga. Like Hagen, Cromwell schemed and recommended means—usually theft, extortion or murder—by which his patron (the King of England) could obtain absolutely anything while still managing to keep his hands and image clean. That they (Hagen and Cromwell) both described themselves as “lawyers” is no small coincidence. Cromwell and his machinations are the focus of The Royal Shakespeare Society’s production of Wolf Hall, Parts I & II, now playing at the Winter Garden Theater.

Based upon Hilary Mantel’s award winning historical novels, Wolf Hall (Part I) and Bring Up the Bodies (Part II), and adapted for the stage by Mike Poulton, the plays are a somewhat contemporized examination of Cromwell’s relationships with Henry VIII and his eventual second wife, the manipulative and politically ambitious Anne Boleyn. The significance of these interactions is that they ultimately led to England’s departure from the Catholic Church and the foundation of Church of England, spawning an entirely new branch of Christianity, for all intents and purposes. Praise from the Booker Prize committee for Mantel’s novel suggested it was a “a modern novel, which happens to be set in the 16th century,” and that modernity very much informs the theatrical version. What we see and the story we are told are entirely Tudor, but the dialog and interpersonal dealings feel like they could have taken place today. That’s either good or bad, depending on one’s personal preference. It undoubtedly makes the story far more accessible, but it also rings somewhat false. The often trite dialog and social familiarity can, for some, lessen the story’s gravity.

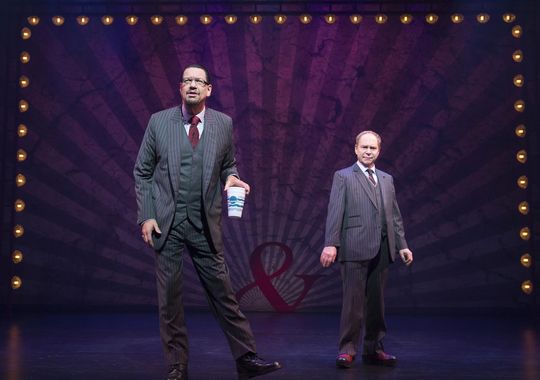

No matter, though, for the plays’ great worth is in both the stunning pageantry of the costume drama and the outstanding performances by the Royal Shakespeare Company actors. Ben Miles’s Thomas Cromwell is undeniably likeable, despite his Machiavellian manipulations in the court. It’s quite understandable, in Miles’s hands, why Cromwell was tolerated, and even favored by the crown despite his less than noble upbringing (which was the subject of constant derision of fellow courtiers). And not only is Nathaniel Parker’s King Henry VIII the spitting image of the monarch as we know him through paintings of the period, but Parker adds unexpected dimension, humanizing a heretofore historical Idea and figurehead ordinarily devoid of personality. There are other compelling discoveries courtesy of some very accessible acting and speech: Leah Brotherhead’s coquettish yet forthright Jane Seymour; Lydia Leonard’s cunning, seductive and politically astute Anne Boleyn; and Paul Jesson, who plays both the jocular (and doomed) Cardinal Wolsey as well as the agèd and amusingly decrepit Archbishop of Canterbury, who unwittingly swears Boleyn’s husband into “confessing” that he’d never in fact married her at all, paving the way for Henry’s annulment from his first wife.

What makes the Wolf Hall stories compelling is that they are as scandalous as any soap opera and not so terribly far afield from a Real Housewives of a New Jersey reality TV show. But unlike those beacons of a failing civilization, the 500 year old stories behind Wolf Hall lay the foundation for modern society. So, being able to digest the plotlines so easily and in so relatable a fashion is both Ms. Mantel and director Jeremy Herrin’s great achievement (especially with Herrin’s silky smooth scene transitions, which seemingly morph from one into the next, thus quickening the pace and flow). They have managed to make this all-important history lesson a bodice-ripping page turner without sacrificing the integrity of the story. On stage the lesson is further conveyed through absolutely stunning period costumes, courtesy of Christopher Oram. And Oram’s very minimalist set is given unexpected dimension by Paule Constable and David Planer’s mesmerizing lighting, whose subtle changes have an impact as powerful as a new set. At one point, as Cromwell interrogates one of Anne’s accused lovers in the Tower of London, bars of light and shadow surround the condemned, creating a better illusion of prison than could an actual iron gate.

Ultimately, this is Cromwell’s story, and we witness the history he manipulates via his own life story, though he remains enigmatic all the while. “I have never known what’s in your heart, do not presume to know what’s in mine,” he tells Boleyn. Indeed, we do not, nor will we ever, know what motivated these two. What we do know is that they forever changed the course of world history. Wolf Hall, Parts I & II at least lets us take a peek at how it happened.

Wolf Hall Parts I & II. Through July 5 at the Winter Garden Theater (1634 Broadway between 50th and 51st Street). www.wolfhallbroadway.com