By Samuel L. Leiter

It’s hard to write critically about a play that affects people so deeply that you feel like embracing those applying hankies and Kleenex to their tearstained faces. Such is the dilemma with D.C. Fidler’s Boogieban, an award-winning, deeply heartfelt, but somewhat too contrived examination of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

In general terms, Boogieban is not very different from the now cancelled HBO series “In Treatment,” in which psychotherapist Dr. Paul Weston, himself having psychological issues, provides penetrating analyses of his patients. If Dr. Weston were a lieutenant colonel in the US military, as is Dr. Lawrence Caplan (David Peacock), his counterpart in Boogieban, the play could easily fit within the TV show’s framework. In fact, one of the latter’s characters was a pilot suffering from PTSD after serving in Iraq.

Boogieban comes to New York following its premiere at Akron, Ohio’s non-too-fragile theatre, with subsequent showings elsewhere. It deals with an issue of significant concern although one that has seen just as or even more potent depictions of the PTSD crisis. The list would include such movies as The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) and Coming Home (1978), and plays like Medal of Honor Rag (1976) and Cry Havoc (2015), the latter even having invited vets to share their stories in a post-show talkback.

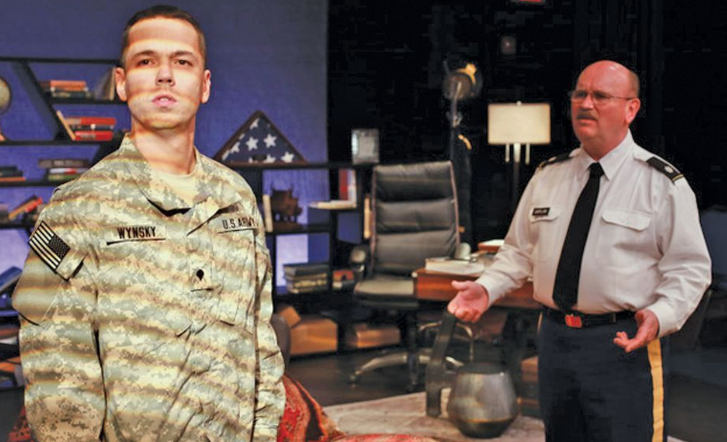

In Boogieban, its title a soldier’s epithet for the Taliban, a disturbed young man, Specialist Jason Wynsky (Travis Teffner), is referred to Lawrence, a Vietnam veteran days from retirement, for help in ridding him of his nightmares. All the action takes place in Lawrence’s bookcase-lined office—sparingly designed by director Sean Derry—with a desk, patient’s couch covered à la Freud with an Oriental rug, and therapist’s chair. Book-filled boxes occupy a corner of the stage.

Fidler (himself a psychiatrist) sets his two-hander in Washington, D.C. in 2010, creating a series of more-or-less straightforward sessions interrupted by the shrink’s fourth wall-breaking, expository soliloquies. These concern his retirement, which he plans to spend on his sailboat; the recent loss of his son, James, a gay soldier who recently died in combat; frictions between him and his wife; and, most pertinently, intimations of his own stress and its consequent nightmares, set in motion after he was seriously wounded fighting the Viet Cong. Lawrence also fulminates angrily about the ethical complexity military psychologists confront when their duty requires them to repair men so they can be sent back to the hell of war.

As often in such dramas, the therapy sessions are cat and mouse games, with the sincere analyst and the cynical analysand trying to outfox each other as their relationship and mutual trust evolves. Jason’s hardscrabble background is one of abuse and low expectations. His edgy behavior is such that Lawrence is prepared at any moment to press the panic button on his desk.

There’s a lot of conversation about books (whose teaching value vs. experience is questioned), friendship, drinking, sex, and so on. Meanwhile, the potentially dangerous soldier works through his emotional ordeal regarding the death in Afghanistan, by hostile or friendly fire, of his beloved buddy, whose dog tag he wears as a bracelet.

Eventually, Jason, under Lawrence’s probing guidance, has his big breakthrough, enacted against a vivid soundscape of battle sounds excitingly captured by designer Brian Kenneth Armour, and lighting effects designed by Marcus Dana. Both patient and doctor find their paths through the shrapnel of their experiences to come out, not unscathed, but somewhat closer to exorcizing their demons and finding peace of mind.

Fidler’s language veers from the realistic to the self-consciously poetic (“You keep a stiff face but feelin’s blow outta you like a desert twister”), softening the play’s visceral impact with touches of verbal staginess. Both actors, however, do insightful work, making their characters convincingly real, a difficult thing in such a small theatre.

Peacock, though, succeeds mainly when he has something strong to play, as in his soliloquies. During the therapy sessions his presence too often dissipates, partly because of director Derry’s lethargic pacing, with long stretches that drag interminably over the course of its nearly two, intermission-less, hours. One also might question Teffner’s rather lax military manner when Jason first meets Lawrence, his military superior.

While there’s not much here that hasn’t, in one form or another, been seen before, plays like Boogieban continue to be necessary reminders of the costs of war—financial, moral, physical, and psychological—even when the fighting ends. And for reminding us to keep addressing those costs, we must thank D.C. Fidler and his troops for their service.

Photo: non too fragile

Thirteenth Street Repertory Theatre

50 W. 13th St., NYC

Through September 29