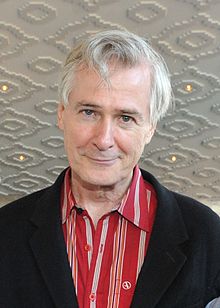

JOHN LEE BEATTY, PORTRAIT OF THE DESIGNER AS A YOUNG MAN: A LOST INTERVIEW

Part 10: “Sometimes You Have to Goose up the Production so It’s More Wonderful.”

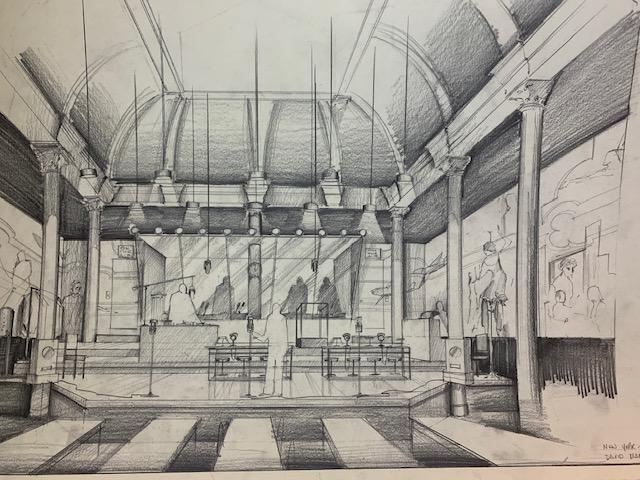

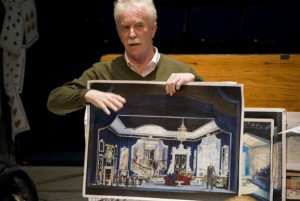

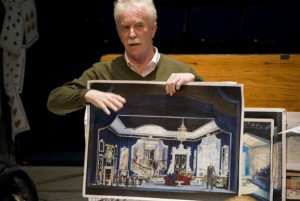

The Water Engine – Martinson Hall, Public Theater

As told to Samuel L. Leiter

This is the tenth installment in my previously unpublished 1980 interview with designer John Lee Beatty, which is being serialized in Theater Pizzazz. Please see Part 1 for an introduction to the interview, which I’ve adapted as a narrative, and why it’s first being published 40 years after it occurred.

On the whole, Broadway’s audience expectation is quite different from most of these Off-Broadway places. We had a meeting about this for Talley’s Folly. When you go to Broadway and there’s a set sitting there, or not sitting there, whatever the case may be, the audience expects very little, so everything that’s wonderful they think is extra-wonderful. When you go to Broadway, people are expecting their money’s worth and they expect something wonderful to start with. Sometimes you have to goose up the production so it’s more wonderful.

At Sheridan Square, the smallness of the room as opposed to the largeness of the set is really rather stunning. In fact, when we moved plays from Sheridan Square they actually have sometimes gotten smaller in physical space than they were. It’s really, really funny, having to make the set smaller when you go to Broadway.

I don’t have any unique vision of what design should be. I must, but I don’t know what it is. I don’t think there’s a rule for anything. I remember I was on a panel discussion once, and [the great designer] Boris Aronson was on the panel with me, and they said, “How do you feel about white light?” What they wanted him to say is, “I insist on only white lighting in my shows because of . . .” Or, “I hate it because it . . .” I don’t remember exactly what he said but it was something like, “White light’s white light. What do you want me to say? The rules change, the rules change.”

There’s a virtue in inconsistency. I may feel one way about theatre today and I may feel another way tomorrow. What is interesting to me as a designer is I design a show maybe three months ago which is first being built now, and by the time it gets on stage I may feel completely different about the design than I did when I designed it. In which case, I’m acting as my own assistant. I say, “I have to follow the design that he did.” I don’t feel this way anymore but I have to complete it. It’s like a child that came out this way—you have to bring it up.

Sure, I study the work of other designers. Everybody does. We all steal from each other. Just like my students in class. They come in with sets that look suspiciously like mine. I don’t think there’s anyone who’s a particularly great influence. I saw so many of those Oliver Smith musicals, I’m sure there’s a lot of that in me. I think Jo Mielziner was brilliant for his sense of scale, especially in a dramatic piece. He just knew what size to make things. That’s a real, real difficult area of designing. Maybe he was just gifted with the right sense of scale.

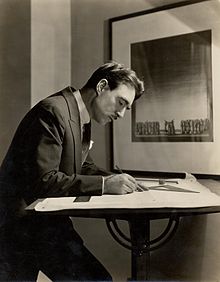

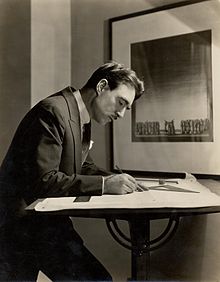

Robert Edmond Jones

Howard Bay does nice woodwork and Boris Aronson does interesting things with throwing a lot of different elements together and stirring it up in a nice way. I love Robert Edmond Jones. I don’t know too much about him but I love him. Gordon Craig? I don’t respect Craig very much. (I know this is awful of me. I know he’s a visionary.) He didn’t know the nuts and bolts especially.

A lot is expected of us designers. You’re expected to be dizzy and with your head in the clouds but you turn around and you have twelve phone calls about the price per inch of this item as opposed to such and such or get questions about what’s the best construction technique or you have to turn out these technical drawings which you try to make perfect and clear.

So it’s a really odd combination, which is perfect for me in terms of my just suiting a profession in being very down to earth and completely out to lunch at the same time. You have to be that as a designer. You have to leave your head free to design but you have to come down to reality all the time.

I love certain painters, not people you’d expect. I love Vuillard, and John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, Whistler, and Botticelli, but I don’t think you can tell especially. Vuillard, I think, shows up maybe in some of my little cozy sets.

I don’t think that a designer must constantly read about and study the classical designers of the past. But put any designer within ten feet of a book of designs and you’ll see him flip through it. In fact, we joke about it. We’ll say, “Did you see such and such a play? I know what page of what book that came from.”

And there are certain sets that we all know that the general public doesn’t know and maybe even directors don’t. But we know, we’ve seen. Lots of people love to rip off from the Germans because it’s a different style from ours. And it looks like you’re a real thinker. We all do that. I like to look at those books. I don’t study design per se, I suppose.

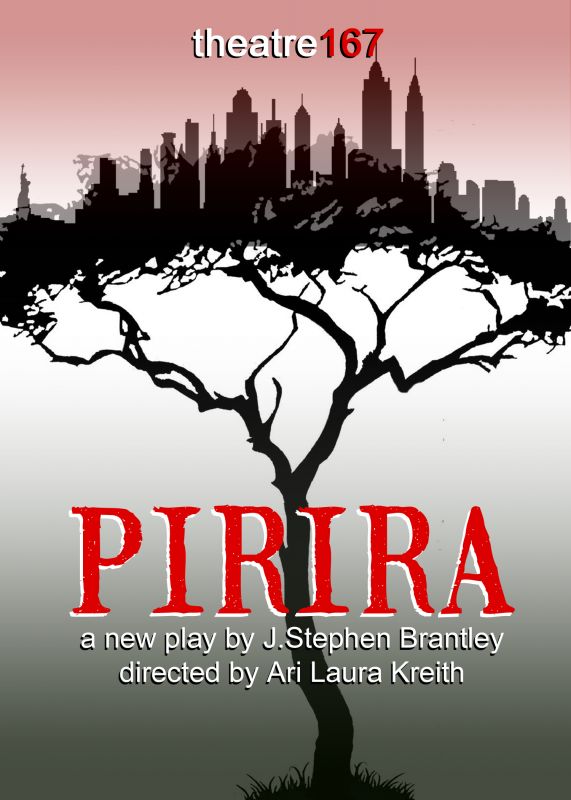

I wouldn’t say my own designs can’t be related to the work of the conceptualists. Look at some of the David Mamet plays I’ve designed. The Water Engine, for example. I did another one out in Chicago that was really rather similar. Even more of that type of theatre. People don’t know I do that kind of stuff. The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs was that kind of show.

Thinking in concepts is fun. I love developing things that way. Don’t get me wrong. If a director comes in and has a design he wants, that doesn’t disturb me as much as having to be the errand boy.

(To be continued.)