Kelley Curran, Jessica Frances Dukes, Matthew Amendt.

By Samuel L. Leiter

I recently watched the first in Netflix’s three-episode series, “Dracula,” inspired by Bram Stoker’s 1897 gothic horror novel. However, I wasn’t bitten deeply enough to view the later episodes. After experiencing Kate Hamill’s very loose, borderline campy, feminist take on the story in Dracula—at the Classic Stage Company through March 8—I may give the Netflix version another chance.

Ever since the novel’s publication, we’ve been inundated with vampire stories—on pages, stages, and screens—some based on Stoker, others original. Like our fascination with zombies, the flood of fangs seems to be getting stronger. Perhaps such stories help to purge our fears of the real bloodsuckers and walking dead among us by retellings that mollify us by being fictional. On the other hand, the goal often is to kindle laughter as well as fear. (Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein—which includes Dracula—remains one my most traumatic childhood memories.)

Over the past few years, Hamill, who acts in her own work, has been crafting a noteworthy niche as an adaptor of 19th-century literature (for example, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Vanity Fair, Little Women). Typically, a Hamill adaptation creates an indeterminate ambience that both takes the original seriously while simultaneously parodying it. Gender identity issues are invariably heightened, as they are in Dracula, her “feminist revenge fantasy.”

Matthew Saldivar, Kelley Curran, Kate Hamill

However, unintended as it is, the play’s emphasis on “a kind of primordial/disease . . . /a plague as in ancient times,” as enumerated by the mad Renfield, is uncomfortably reminiscent of the one spreading around the globe. Nor, in the wake of a certain movie, will audiences be unmindful of references to parasites.

Amusingly directed by Sarna Lapine in the same three-quarters round configuration and seemingly on the same platform as the CSC’s recent Macbeth, Dracula is designed by John Doyle in his usual minimalist manner. It uses few scenic elements, mainly an upstage curtain and a white hospital bed.

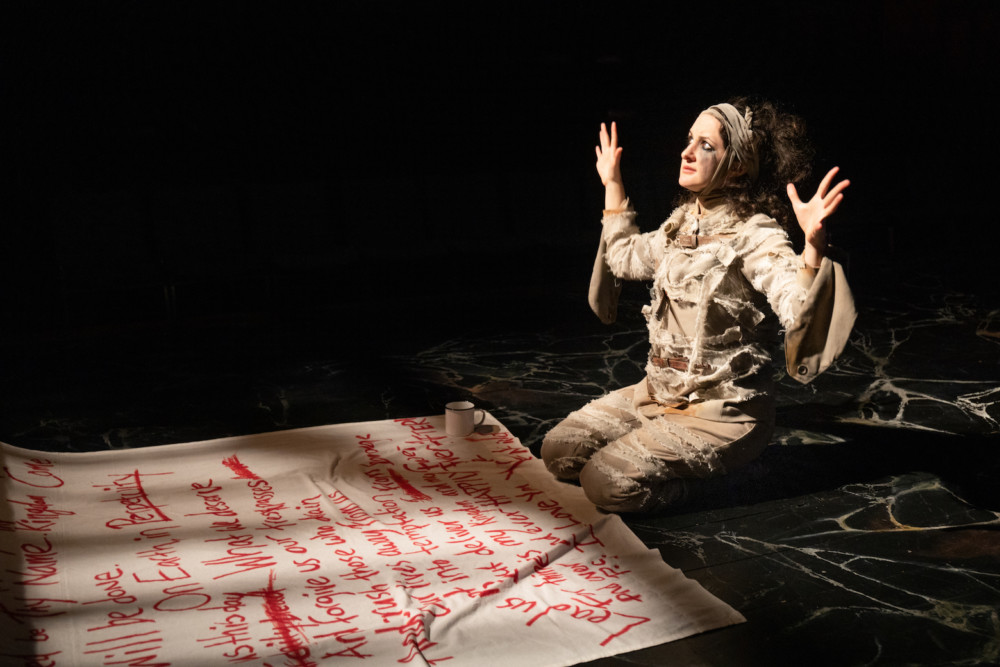

Robert Perdziola’s costumes, most of them white, hint at both the late Victorian and modern eras. Blood is visible not in liquid form (as in the script) but as red-sequined fabric. Adam Honoré’s lights and Leon Rothenberg’s sound evoke somber eeriness. And, while there are no fangs, crucifixes, garlic, and wooden stakes play their parts.

Kelley Curran, Jamie Ann Romero, Jessica Frances Dukes. Photo by James Leynse,

The outlines of Stoker’s plot prevail. It begins with the proper British lawyer, Jonathan Harker (Michael Crane), bidding farewell to his pregnant bride Mina (Kelley Curran), as he departs for the Carpathian castle of the predatory Count Dracula (Matthew Amendt, slickly handsome in a long, white coat). His mission is to aid the nobleman in moving to England.

There, Dracula already has a victim awaiting his arrival, the aforementioned madwoman, Renfield (Hamill), a man in Stoker, a woman in Hamill. She prays to Dracula as if he were her godly father. Caring for her is Dr. George Seward (George Saldivar), head of the insane asylum, affianced to Mina’s friend, Lucy Westenra (Jamie Ann Romero).

Dracula, under pressure from the local peasants, seeks juicier prospects abroad for himself and his ravenous minions, Drusilla (Laura Baranik) and Marilla (Lori Laing). They, though, harbor incipient antagonism toward his patriarchal authority, a theme later echoed when Mina and Lucy object to being patronized by men. Mina, a liberated woman who bristles when her reactions are called “hysterics,” exhorts Lucy to be honest with Seward or “risk a lifetime of unhappiness.” Inevitably, Mina will move beyond her own ladylike behavior.

Lori Laing, Michael Crane, Laura Baranik, Jessica Frances Dukes.

Just as Lucy, having become Dracula’s latest drinking fountain, shows signs of vampirism, who should show up but the vampire hunter Dr. Van Helsing (Jessica Frances Dukes). Stoker’s character, though, like Renfield, is now a woman, in her case a tough-talking, contemporary American in brown leather jacket, cowboy hat, and scarred face. “What, you were expecting a withered old Dutch man?” she snaps. (Netflix’s Van Helsing, by the way, is an atheist nun, sassier even than Hamill’s. Maybe I will continue watching.)

As the action proceeds to its inevitable conclusion—including a cheesy, extended fight (staged by Michael B. Chin) with stakes that look like chubby pencils—Van Helsing becomes the focus while Dracula is mostly out of sight (in his coffin?). Hamill wants to foreground her females’ strength and detoxify her males, particularly the officious Seward.

The actors have fun, performing with just enough dryness to maintain a basic level of reality, but stopping just short of confessing it’s all a bunch of hocus pocus. Even with its up-to-date tics, thematic slings, and occasional laughs, however, Hamill’s Dracula runs out of blood before its nearly two and a half hours signal R.I.P.

Dracula. Through March 8 at Classic Stage Company (136 East 13th Street, between Third and Fourth Avenues). www.classicstage.org

Photos: Joan Marcus (except where indicated).