by Samuel L. Leiter

Eva O’Connor’s patchy, pro-choice dramedy, Maz and Bricks, now at 59E59 Theaters as part of Origin’s First Irish, is yet another example of the current trend that uses one of theatre’s hoariest devices, the aside, as a playwriting tool sharing an equal, if not dominant, place with dialogue.

The aside, of course, occurs when characters break the fourth wall to share their thoughts directly with the audience, while no one else on stage hears what’s being said. A perfect example of its traditional use is the current revival of London Assurance at the Irish Rep. Although no longer standard, it continues to be used, often for self-conscious comic effect, by writers for stage and screen.

A number of recent plays, however, especially Irish ones like Maz and Bricks, have been flipping the convention, essentially making the dialogue (when it even exists) secondary to the aside. In other words, the playwright conveys the bulk of the story through monologues, the solo narratives often introducing other characters, while everyone else stands by. Recent examples that come to mind include Grasses of a Thousand Colors, The Emperor, The Sound Inside, Little Gem, Molly Sweeney, and Pumpgirl.

Maz and Bricks begins conventionally enough, with two young people, Maz (Eva O’Connor, the playwright) and Bricks (Ciaran O’Brian), meeting cute on a LUAS tram into Dublin. Their dialogue devolves into multiple speeches of direct address, now and then broken by normal conversation. Regrettably, neither the situation, the language, the plotting, the flashes of humor, the performances, the direction, the 80-minute running time, nor even the provocative abortion-related theme can save the play from flat-lining.

Produced by the Irish company Fishamble (Charolais) in a dozen Irish venues (including the Edinburgh Fringe) to coincide with Ireland’s 2018 referendum on the Eighth Amendment, aimed at removing the constitution’s ban on abortion, Maz and Bricks stirred considerable discussion about this hot potato issue. O’Connor’s program note says of the referendum’s successful passage, “As a woman who has had an abortion, it felt like waking up to an Ireland that has accepted me.” Heartfelt as it is, though, her play leaves much to be desired.

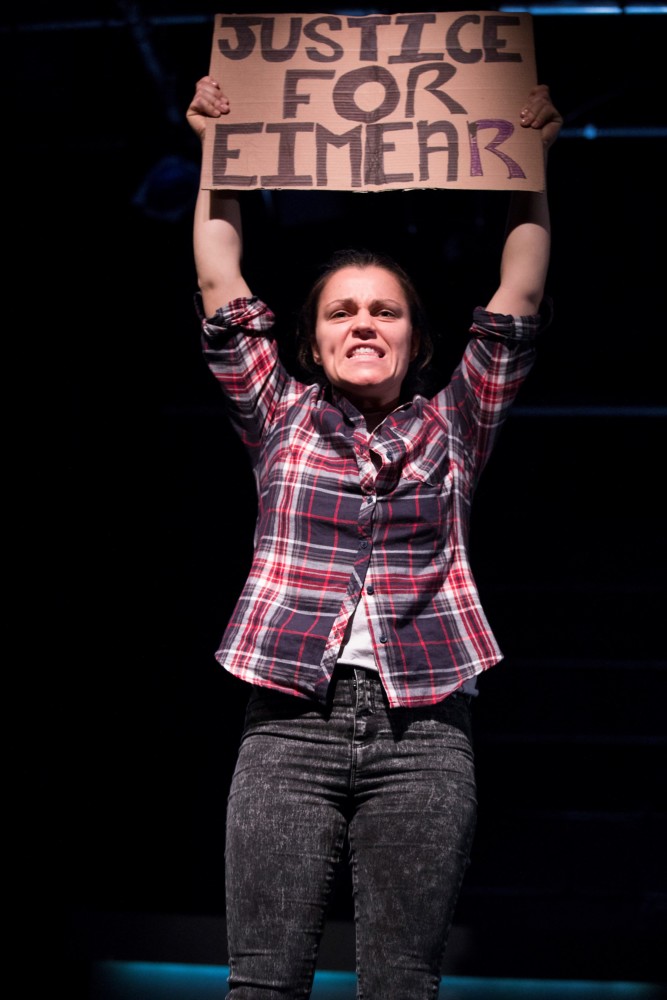

Bricks is a recovering alcoholic, grieving for his brother, whose death by suicide a year earlier is about to be commemorated in a Catholic mass. A garrulous would-be charmer, as well as a divorcé with a four-year-old daughter, Yasmine, he conceitedly thinks Maz is drawing a portrait of him. In fact, Maz is making a placard, being on her way to a pro-choice protest march following the death of woman who’d been refused an abortion. For his part, Bricks, headed to pick up Yasmine from his ex-wife, is “on the fence” about the issue.

Naturally, Maz and Bricks’s differing views—spiced by their mutually tart reactions (he calls her his “favourite abortionist”)—expressed in rich but not always clear patois, spark a budding romance. But first, in a back and forth series of monologues, we must hear about Maz’s fraught experiences at the march, and Bricks’s confrontation with his seething ex-wife, whose cousin he (ignorantly) shagged the night before.

As Maz and Bricks’s friendship warms, cools, and warms again, the abortion issue recedes in favor of the usual romantic complications, making the socio-political problem feel less like a thematic imperative than background color for a play about angry, depressed, and alienated people struggling to connect.

This includes Maz’s relationship with her mother, who turned against her daughter after she was raped, got pregnant, and had an abortion. Will she call her mam, as Bricks urges? Will Bricks’s wife relent and let him see Yasmine? Will Bricks and Maz unite? Whatever its cri de coeur intentions, Maz and Bricks has a few too many things on its mind.

Under Jim Culleton’s direction, the actors offer energetic but not particularly engaging performances of characters who must embody their angst in a sea of dense poetic prose filled with local references, occasional rhymes, and casual profanity. The reliance on monologues, which include other people whose presence can only be hinted at, creates a distancing effect that seeps into the actual dialogue scenes. It’s a difficulty that better directorial orchestration might have resolved.

Maree Kearns, who also did the quotidian costumes, has designed a nearly bare setting of neutral, gray units, Sinéad McKenna has provided nicely variegated lighting, and Carl Kennedy’s sound is sufficient unto the play. But Maz and Bricks lacks enough mortar to hold the construction together.

Maz and Bricks. Through February 23 at 59E59 Theaters/Theater A (59 East 59th Street, between Park and Madison Avenues). 80 minutes, no intermission. www.59E59.org

Photos: Lunaria except as otherwise indicated