By Marilyn Lester

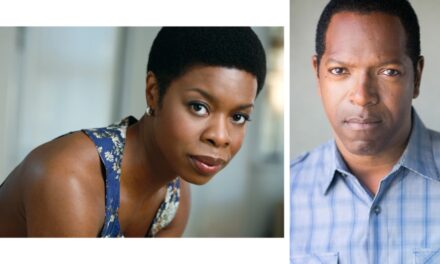

As you enter 59E59’s Theater B, the star of One November Yankee is remarkably and stunningly apparent—a full-sized, single-engine, yellow Piper J-3 Cub, crashed nose down, but mostly intact. The little plane’s serial number, 241-NY, which gives title to this work, is blazingly prominent on its fuselage.This is the focal point around which two actors, Harry Hamlin and Stefanie Powers, inhabiting six characters in three interlocking stories, will play out the tragedy of this plane’s fate.

One November Yankee is, at its best, a mediation on what classical Greeks referred to as storge—familial love, a powerful, supportive love that’s just as prone to disintegrate into chaos when family goals don’t align. In the three sets of brothers and sisters who inhabit this work, such conflicts are explored with varying degrees of success. Author Joshua Ravetch is an articulate writer, but also a glib one, a facility that largely enfeebles the three stories—more so because people don’t speak to each other as if they’d just stepped out of a Noël Coward play. Such archness may be occasionally amusing, but it certainly undercuts the valid points the playwright is striving to make. Likewise, Ravetch’s relentless reliance on expletives, which aid and abet his compulsion to be funny, plus his single-minded focus on the bickering between the siblings, detract from the possible depths the play could have achieved.

One November Yankee is bookended by the story of Ralph and Maggie; he is a sculptor who has created the crashed Cub as an art installation, based on a five-year-old newspaper article about the missing plane. Maggie is the art curator who’s gotten her brother the grant to create the work, which she finds, like most of his art, incomprehensible. In the next segment of the play, the crash has just occurred in the early-winter mountains of New Hampshire. Siblings Harry and Margot have ditched and will eventually make the news as having never been found. She’s in good shape, but Harry has a badly broken leg. The wreck is the result of Margot’s incompetence, triggering this pair’s squabbling into a bitterly cold night that will threaten their survival. Finally, hiker brother and sister Ronnie and Mia come across the plane, about one week before Ralph’s art installation opens in New York. The revelation triggers an argument over their older brother’s death in a plane crash 22 years before. It’s this part of the story that holds the key to the very last scene of the play, a brief post script that’s a last clever bit thrown in—make of it what you may.

Ravetch, as a cleverness junkie with an addiction to flippant repartee, is ultimately One November Yankee’s undoing. Cross references galore are dotted everywhere; there are interwoven references to 9/11, failed marriages, dentists, law school, Mt. Rushmore, an artist named Kantano and so on. These overdone bits, while amusing, also detract from the potential power of the work. They certainly don’t add anything to it. Yet, when all is said and done, there is a core of undeniable value to One November Yankee. It’s a keen study of the butterfly effect on lives that entwine and interact in ways often mysterious. And, of course, One November Yankee is a journey into the equally mystifying world and nature of sibling rivalry and sibling revelry.

Author Ravetch, who also directed this production of One November Yankee, similarly directed its 2012 premier in Los Angeles (with Hamlin and Loretta Swit). This revised edition, the East Coast premiere, is a production of the Delaware Theatre Company. While this mounting would have been better served with a director who might have brought some fresh points of view to the work, Ravetch is fortunate that the acting prowess of Hamlin and Powers elevated the work to the heights it did achieve.

Set Design is by Dana Moran Williams, with costumes by Kate Bergh, lighting design by Scott Cocchiaro and sound design by Lucas Campbell.

Photos: Matt Urban – NoPoint Marketing

One November Yankee plays through Sunday, December 29 at 59E59 Theaters, 59 East 59th Street, NYC. Tickets are available by calling the 59E59 Box Office at 646-892-7999 or by visiting www.59e59.org. The approximate running time is 80 minutes with no intermission.