by Marilyn Lester

There are individuals who come into this world larger than life and twice as wide. Jazz pioneer, virtuoso trumpet player, vocal innovator, actor, international celebrity, and force of nature, Louis Armstrong, was one of them. Universally loved by the world at large, Armstrong was a man who left a huge footprint on the historical and cultural trajectory of the 20th century.

In his first play, Satchmo at the Waldorf, playwright Terry Teachout, former jazz bassist and currently the drama critic at The Wall Street Journal, attempts to capture all of this, from Louis Armstrong’s 1901 birth in New Orlean’s notorious Storyville, to his death at home in Corona, Queens in 1969.

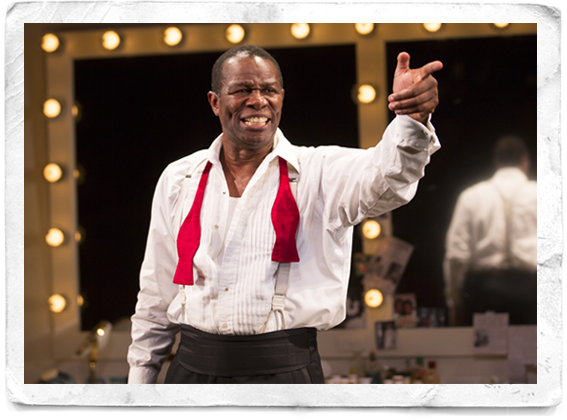

The star of Satchmo at the Waldorf is Obie and Lortel Award winner John Douglas Thompson, who not only plays Armstrong, but switches gears to give life to Armstrong’s manager Joe Glaser, and jazz trumpeter, Miles Davis. From the moment an aged Louis Armstrong, bursts into his Waldorf Hotel dressing room (an elegant recreation by Lee Savage), and lunges for an oxygen tank, it’s obvious acting greatness is about to commence.

Scholarship since Armstrong’s death has revealed much more about the man, putting many of the “real” aspects of his life in perspective and historical context. Terry Teachout’s book, Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong from which this play is drawn, is one among many to delve deeper into the complex Armstrong persona – including peeves and vexations, views on race, daily marijuana use, and other private matters not generally known to the wider public.

Satchmo at the Waldorf tells the story of Louis Armstrong through the lens of his long relationship with manager Joe Glaser, the black sheep of a wealthy Jewish family of physicians. It’s widely known that the racial prejudice of the times meant black entertainers needed the patronage of a white man to succeed. This was the system and everyone knew how it worked, like it or not. Joe Glaser took care of business, while Louis had the freedom to perform as he chose, while making money hand over fist for both of them.

Moreover, the sparring between Glaser and Armstrong is expressed in a relentless stream of “F” words, “M” words and two “C” words. There’s not much let-up, so don’t bring the kids. Many situations are also rather crude and crudely recounted. Sure, both Glaser and Louis swore. Armstrong was also fond of scatological jokes and discourse, but even a man who likes steak eats a vegetable now and again.

Culturally and historically, blacks have long struggled to balance advancement with “selling out to the white man.” There were those who accused Armstrong of being a singing, dancing, clowning Uncle Tom. These included some of the young newcomers to jazz, especially Dizzy Gillespie. But by 1970 at the Newport Jazz Festival, a more mature Dizzy said of Armstrong, “If it hadn’t been for him, there wouldn’t have been none of us. I want to thank Louis Armstrong for my livelihood.” Louis knew Dizzy had recanted long before he died; the two even worked together. Likewise, that iconoclast of the jazz world, Miles Davis, had, contrary to his accusing dialog in Satchmo at the Waldorf, a great respect for Louis. He said in a 1962 Playboy interview: “I love Pops, I love the way he sings, the way he plays… People really dig Pops like I do myself.”

The dramatic climax of Satchmo at the Waldorf is the death of Joe Glaser. During the summer of 1957, Glaser was visited by the Chicago mob and forced to hand over control of Associated Booking. In the play, Louis discovers that Joe has left him nothing in his will. Glaser was too chicken to tell Louis about the deal. Louis feels utterly betrayed. Eventually he decides to forgive Glaser and move on. To the contrary, Glaser willed Louis Associated’s music publishing company, International Music, as well as money in savings accounts and trust funds he’d been holding for Louis and Lucille.

Despite the extravagant coarseness of the dialogue, and the manipulation of facts, the question is, does Satchmo at the Waldorf serve Louis Armstrong’s legacy? The late Phoebe Jacobs, Armstrong’s publicist and close personal friend, said on many occasions she believed Armstrong to be an angel sent to this earth. Dizzy Gillespie summed up Louis when he said Louis’ life represented “an absolute refusal to let anything, even anger about racism, steal the joy from his life.” Terry Teachout would be among the first to tell you Louis Armstrong was a genuinely good man. When the character of Louis Armstrong exits his dressing room to go home to his Lucille, we cannot fail to realize that a giant of a man has left the building.

Costume Design for Satchmo at the Waldorf is by Ilona Somogyi, Lighting Design by Kevin Adams, and Sound Design by John Gromada, all offering understated enhancement to the brilliance of Thompson’s characterizations as directed by Gordon Edelstein.

*Photo of John Douglas Thompson by T. Charles Erikson

Satchmo at the Waldorf, Westside Theatre/Upstairs, 407 West 43rd Street, New York, NY 10036. (212) 239-6200. Telecharge.com