By Barbara & Scott Siegel

Where Wolf Hall Meets Hamilton:

Two of the most high profile shows of this season, one a drama from the Royal Shakespeare Company that has come to Broadway, Wolf Hall – Parts 1 & 2, and one a musical, Hamilton, recently performed at The Public and now preparing its Summer move to Broadway, both have at their centers strikingly similar heroes.

In both cases, the characters of Thomas Cromwell (Ben Miles) and Alexander Hamilton (Lin-Manuel Miranda) are unexpected protagonists of major historical stories. For generations, when tales about either the Tudors or the American revolution have been told, these characters have not been portrayed as the movers and shakers of their day, but rather as second tier performers (if portrayed at all). Suddenly, in the same theater season, two self-made men, who rose to prominence and power in a world otherwise dominated by the landed aristocracy, have had hit shows written about them.

Considering how Americans, in particular, are so fond of the underdog, it’s rather amazing that it took so long for Alexander Hamilton’s story to get told. If ever there was a founding father that embodied the American Dream – even before there was such an expression – it was Hamilton. Born into poverty, self-educated, living by his wits, he came to America and helped shape a nation – and in many ways, he gave the United States its soul. Or so Lin-Manuel Miranda’s warm, embracing and exciting new musical would have us believe.

Wolf Hall, by contrast, establishes its outsider hero, Cromwell, as a sympathetic man trying to survive and prosper in a world where one wrong step, one mistaken alliance, can send a man to the Tower. He’s a hero largely because everyone else is worse than he is. But audiences respond to him because he is always the underdog, having to use his wits and wile to out-maneuver people with more power and wealth. If he is ultimately ruthless, we forgive him because he is destroying enemies who have done evil to others and they deserve their comeuppance.

While Hamilton and Cromwell are surprisingly similar characters in the worlds they inhabit, the shows in which they appear ultimately take their protagonists to two very different theatrical places. While Wolf Hall is an entertaining slice of history, told from an original point of view (meaning that of Cromwell), it is ultimately more about the novelty of telling an oft-told tale in a different, theatrically fluid style, cramming an enormous amount of history into a five-and-a-half hour opus that could have easily been twelve hours in less capable hands. On the other hand, one is not moved even once, in this show. So efficient is the story-telling that we never live long enough with any one situation to fully invest ourselves in its characters. They are pawns in a big historical chess game. And even the King and Queens are merely pieces to be moved from here to there. It’s engaging and well-done, but it has no real heart or passion in it.

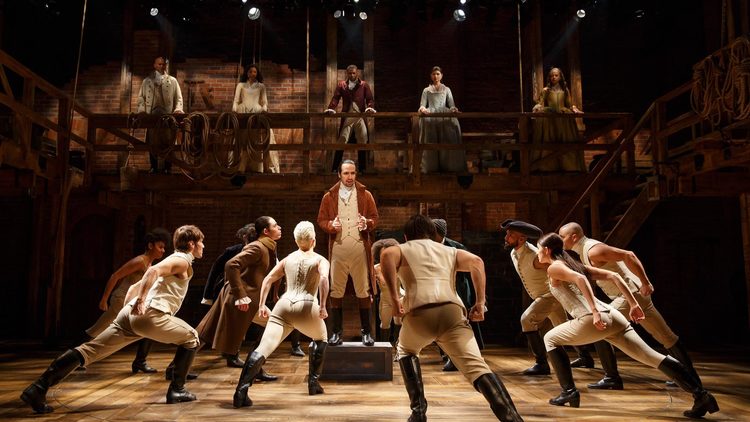

Hamilton, however, is another story – quite literally. It’s very casting of an ethnically diverse universe of Black and Latino actors playing our Founding Fathers makes both an elegant intellectual and emotional point about our immigrant society. It doesn’t state its point; it shows its point.

We would claim for Hamilton that its sensational combination of unique Americana — combining the history of revolutionary America with the energy, style, and imagination of today’s cutting edge creatives, Lin-Manuel Miranda (composer/writer) Andy Blankenheuler (choreographer) and Thomas Kail (director) — has given us a musical that will be as important and ground-breaking for the history of musical theater as Oklahoma! was when it hit the boards in 1943. And for much the same reasons…

Oklahoma! was groundbreaking because of the way it told its story. One of those innovations was the introduction of a new form of dance added to Broadway with Agnes DeMille’s dream ballet. By the same token, Andy Blankenbuehler’s swirling, virtually non-stop choreography is also genuinely new to Broadway, building on the style that he pioneered in In The Heights.

But like Oklahoma! did in the midst of World War II, Hamilton arrives at a time when America needs to regroup and rekindle its essential values. Then, as now, we, as a people, turn to popular art to find what it is that makes us a great nation. In 1943, it was the sense of American values from the heartland that gave us our character. Now, with Hamilton, with its largely hip hop score (the beat of the city rather than rural America), it tells a story about the very nature of our people, our sacrifices, and our reach for something no other nation has ever achieved before (or since). It acknowledges our flaws, embraces our humanity, our sense of family, of honor, and even our ambition. It’s as big and full of bursting energy as America, itself.

Simply put, Hamilton is an extraordinary achievement.

Saint Ives:

Some playwrights have a style and sensibility so singular that one is hard put to find anyone else writing in the same manner. Enter David Ives. Not only is his writing style distinctly his own, even his form is something unique in this modern age: he occasionally writes one-acts and puts them together into an omnibus – and people come to see them. How rare is that?

His latest collection of inspired comic craziness is called Lives of the Saints. The Primary Stages production at The Duke Theater has since closed, but like his earlier collection, All in the Timing, which was both brilliant and much produced elsewhere, Lives of the Saints will surely be seen hither and yon. While it isn’t as completely satisfactory in all of its pieces as its predecessor, some of the one-acts are so drop-dead funny in their insightful humor that one easily forgives the ones that are simply good, not great.

Of course, Ives has written a great many other works outside of the omnibus universe, but these short plays find their closest comparison in the short stories that Woody Allen wrote for the New Yorker that were collected into books of comic short stories, Getting Even and Without Feathers. And perhaps that is the greatest compliment one can give the talented Mr. Ives.