By Stuart Miller . . .

Edward Albee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “A Delicate Balance” runs two hours and forty-five minutes but when it’s done well, Albee’s acerbic dialogue and lacerating commentary on how the protective bubble of wealthy WASPs is disintegrating before their eyes keeps you leaning in for more. That’s what it felt like in 1996 when George Grizzard, Rosemary Harris and Elaine Stritch demolished the pretensions and pretending their characters had lived behind for oh so long.

Sadly, by the time the current off-Broadway production—staged by the Transport Group with the National Asian American Theatre Company– creeps past its supposed run time toward the three-hour mark, it has long since been apparent that this version has serious pacing problems. It’s an issue that starts in the opening scenes and drains the play of much of its humor and emotional punch. Don’t write it off completely, there’s still enough of Albee’s mordant worldview here to savor, but it’s just good enough to make you wish the directing was crisper and some of the acting stronger.

The play takes place in the sumptuous suburban living room of Tobias and Agnes, who air their grievances as they soak their sorrows in an array of alcohols… even while disapproving of Claire, Agnes’ alcoholic sister, who consume so much that, horror of horror, she speaks her very angry mind (and then, admittedly loses control).

Their tenuous peace is about to be shattered by Tobias and Agnes’ spoiled daughter Julia, who is returning home in retreat from failed marriage number four. But before this permanent adolescent can reclaim her room it is commandeered by the couple’s best friends, Harry and Edna. They arrive seeking shelter from an unknown, indescribable terror that snuck in and throttled their placid suburban existence after dinner. It’s this idea that some unspeakable thing– a changing society, a loss of identity—is lurking that drives the play. Harry and Edna do more than overstay their welcome, they act as if it is their divine right because they are the right sort of privileged people. This assertion creates a crisis for the fracturing family as it desperately seeks a return to what passed for normalcy.

This production, directed by Jack Cummings III, features an all-Asian cast. Giving actors of diverse ethnic backgrounds a chance to tackle iconic roles that have traditionally been the province of whites alone is always welcome. But while it’s an admirable idea, it’s unclear that it adds extra resonance, especially in an era where it’s white America that seems to be self-destructing as it tries to cling to a past that was supposedly better and happier. (Contrast that to the current Broadway production of Death of a Salesman, where the Lomans are Black, a choice that offers a stark reminder of how limited economic opportunities still are for Blacks in a white-dominated society)

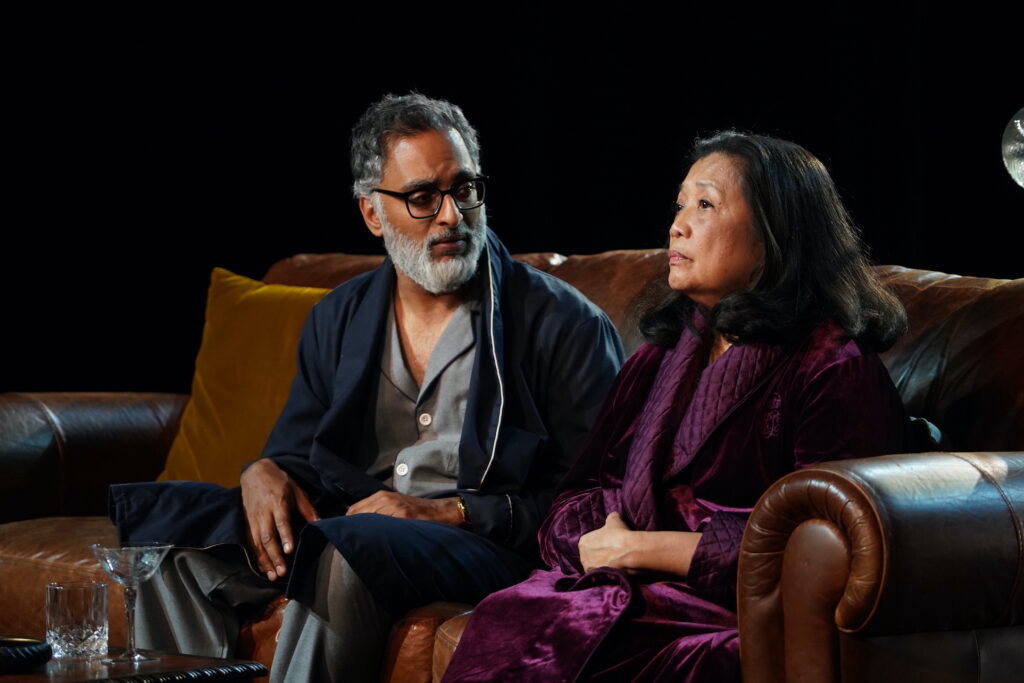

Still, some of the cast makes the most of the opportunity, notably Mia Katigbak as Agnes. As the Obie Award-winning actress muses on her potential descent into madness, she makes Albee’s sometimes stylized dialogue feel spontaneous and lived in. She may be cold and calculating but there’s a weariness underneath, mixed with a steely resolve to score her points and fight for what she wants. Katigbak gives the play an emotional core.

As Claire, Carmen M. Herlihy wields her permanently loosened tongue as a weapon, cutting everyone down to size, although Claire is, like her sister, supposed to be in her 50s and Herlihy appears almost young enough to be Katigbak’s daughter, which is a bit confusing. (By contrast, Harris and Stritch were born two years apart) In a smaller role, Paul Juhn ably displays Harry’s fright but also the confidence and charisma that allows him to take what he wants. As his wife, Edna, Rita Wolf comes off as too stiff and proper— behavior that might feel apt at a country club event but not in their best friend’s living room. Tina Chilip breathes fire into the proceedings as a petulant Julia but gets too worked up too quickly leaving her little room to escalate.

The weak link is Manu Narayan as Tobias. Narayan, who is more than a decade younger than his character, fares well enough when he finally explodes, but he has trouble with the moments of quiet desperation, of which there are many. It often feels like Narayan is playing a role, not inhabiting a character; Albee is, of course, writing about people who are uncomfortable in their own skin and who may seem to be acting at life, but this seems less like an artistic choice and more like an inability to crawl inside Tobias and just be. His artifice undermines the conversations, especially with Agnes and Claire, which is one reason the show feels draggy.

Additionally, while Cummings makes good use of the intimate stage with audience members on both sides of the action, he mismanages the exit—the side of the stage is quite deep, the staircase the characters periodically climb is too high and , therefore, when someone is leaving or entering it slows the pace even more.

There’s a great play and some good performances in there, but this production at The Connelly Theatre, can’t maintain the, you know . . . delicate balance, required to bring it fully to life.

The Connelly Theatre, 220 E. 4th Street, NYC, thru November 19

Photos:Carol Rosegg

Featured Image: (L to R): Manu Narayan, Carmen M. Herlihy, Mia Katigbak, Paul Juhn, Rita Wolf i