By Ron Fassler . . .

No Way to Treat a Lady is a dark comedy thriller novel by William Goldman who, when it was published almost sixty years ago, had not yet gotten his foot in the door in the world of film. He would go on to become a two-time Academy Award winner for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men and become a dean of American screenwriters in his lifetime. Some may remember the film made of No Way to Treat a Lady in 1968 with Rod Steiger, George Segal and Lee Remick, but Goldman had nothing to do with it. He did, however, retain the rights, so when a composer-lyricist named Doug Cohen came to him about obtaining them to make a musical of it, it was only the first of thousands of steps the young writer travelled towards getting it onstage. When it was first produced in New York in 1987, I auditioned for the musical and even though I didn’t get it, have harbored no ill feelings towards Doug these many years (he’s since become a friend).

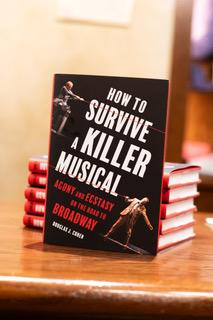

His new book How to Survive a Killer Musical chronicles the trials and tribulations endured as well as the remarkable persistence Doug stomached in getting it done over the course of a number of different incarnations involving a host of directors. I was able to read it before it was published and cheered Doug’s effort to get his story told. If inspiration and perspiration are what it takes to succeed, then this is one sweaty book.

Here are some highlights from a conversation we recently had about the rigors of creating a new work for the theatre and lessons learned along the way.

Ron Fassler: You subtitle your book “Agony and Ecstasy on the Road to Broadway.” Can you qualify in percentages how much agony and how much ecstasy?

Doug Cohen: Great question!

RF: I try.

DC: I’d say it was about 50/50, even though at times the “agony” stands out more than the “ecstasy.” Don’t forget that Sondheim’s “Agony” brilliantly reveals we often feel ecstasy in bemoaning our fate. But anytime I’m given an opportunity in the theater, I’m grateful… even though sometimes it’s “Sorry/Grateful.”

RF: There is an ironic tone to your book about your trials and tribulations. How much of that stems from the fact that in the end the show did not make it to Broadway?

DC: I’m not sure it impacted the tone. When I first kept my diary/journals, I had no idea where my show would lead, although I hoped it would go the distance (i.e. Broadway). With every new opportunity, that hope was rekindled but eventually abated. However, I learned to embrace the journey, even though it was often a bumpy ride. And thankfully, I kept my sense of humor. Perhaps that’s the ironic tone you detected, but humor repeatedly saved me.

RF: But you laughed alone a lot of the time. The fact that you were the book writer, composer and lyricist meant that you had no one else to lean on when it came to rewriting. How big a difference would this journey have been if you had shared it with a partner in the writing process?

DC: A good director can be like a good collaborator. You ultimately are responsible for the work, but I found that Lonny Price, Robert Jess Roth, Vivian Matalon, and Bill Goldman (the author of the original novel) were at times like surrogate collaborators.

Even though it would have been helpful to have a collaborator (for inspiration and moral support), working alone has its definite plusses: You know you’re writing the same show, and there are fewer arguments. You share the same routine, work ethic, and taste in fast food options.

RF: Your relationship with Goldman is a central theme in the book even though there’s a somewhat cryptical nature in your interactions with him through the years. Have you ever thought of how, now that you’re closer to the age he was when you first met him, you might treat a younger colleague coming to you in similar circumstances?

DC: Well, let’s put it this way: If someone in his 20’s or early 30’s asked to musicalize How to Survive a Killer Musical, I’d probably take a meeting. And if they had four great songs and the requisite passion, I might just give them the rights if I haven’t already begun to musicalize the property myself!

Lately, I’ve thought more about mentoring aspiring writers. I was so fortunate to have two mentors in my lifetime: William Goldman and Frank Gilroy (whose movie, The Gig, I adapted as a musical). It was crucial to my development, and recently I was able to help a former student from Neighborhood Playhouse in adapting her first musical. It feels good to give back, and I hope to do more in the future.

RF: Of all the lessons learned during the years of working on No Way to Treat a Lady, can you sum up which lesson was the most profound or had the most lasting effect on your work as an artist?

DC: There were so many lessons I learned: the importance of perseverance, patience, resiliency, and even prayer (well, meditation.) But I think the most important lesson was to be open to input. Nothing is set in stone, and everything can and should be scrutinized in the interest of creating a better show. You also have to be principled and know when to defend work you believe in. But one should always be open to the possibilities of change.

RF: And piggybacking on that, what do you personally do differently in the throes of birthing a new musical today from thirty years ago?

DC: I doubt today that I would take on a full-length musical by myself. I’m older now, and the process has become more arduous, the stakes higher. I feel it would be foolhardy to attempt a solo journey, but I don’t regret for a moment that I took on that assignment.

RF: What was the biggest self-discovery you made while digging up these detailed memories from so long ago?

DC: I know it may sound like hyperbole, but I’m amazed I survived. There were times, especially when I was in London for nearly three months, when my self-esteem was very low. I was also in a foreign country where I mistakenly assumed we spoke the same language. I felt estranged from my family and dear friends. So when things started to head south, I was shocked at how much of my self-worth was tied to the project. There are letters from my parents where they express genuine concern for my well-being. (My wife’s phone bill was off the charts!) Artists need to diversify so they don’t put everything into their work. But when you’re isolated and thousands of miles away, there’s very little to fall back on.

RF: Your book covers it in length, but for someone who hasn’t read it, can you sum up the advice you would give someone in a similar position on how to survive working on their new musical when the going gets particularly rough?

DC: You have to constantly remind yourself what it was about the project that inspired you to make this fierce commitment. Working on a musical is often like a marriage: you’re in it for the long haul, so it’s important to rekindle that love or passion, even when you’re tearing out what little hair remains (and I should know!).

Also, keep a journal. Better to reveal your true feelings on the page where it’s cathartic and safe than in a meeting or at a rehearsal, which can be messy. And at the end of the experience, you have a wonderful reminder of how you navigated turbulent waters… and maybe even the basis for a book!

Featured Image photo by Michael Russell