By Samuel L. Leiter . . .

A Strange Loop, the raucously profane, satirical, Pulitzer Prize-winning musical comedy, which premiered Off Broadway at Playwrights Horizons in 2019, is now jubilantly planted at Broadway’s Lyceum Theatre. Dazzlingly original, the show is a sometimes painful, sometimes joyous, and sometimes comic cry of angst about a fat, Black, gay man writing a musical comedy about a fat, Black, gay man writing a musical comedy about being a fat, Black, gay man writing a musical comedy . . .

In its metatheatrical way, its self-involved main character, the nearly 26-year-old Usher (the remarkable 23-year-old Jaquel Spivey, and no, not that Usher), resembles photos of the show’s book, lyrics, and music creator Michael R. Jackson (no, not that Michael Jackson). He said in a program note for the Playwrights Horizon production that the work “is not formally autobiographical” while confessing to having thoughts similar to Usher’s while writing it.

He also noted how often his name has confused others about his identity; the same is true of his appearance, which has led people (Black and white) to confuse him with the playwright/director Robert O’Hara. This, he declared, has only further encouraged his preoccupation with establishing his own identity. And identity is at the heart of A Strange Loop, a show that, as Usher explains, takes its title from Douglas Hofstadter’s cognitive science term:

“And it’s basically about how your sense of self is a kind of paradox. And how your ability to conceive of yourself as an “I” is just an illusion-cycle of meaningless symbols in your brain that move from one level of abstraction to another but always wind up right back where they started.”

Get it?

Like the paintings of M.C. Escher, the narrative (and some of the music) keeps looping back on itself. But the term also refers to a song by Liz Phair, whose lyrics aren’t particularly loopy. The latter connection seems more attuned to Usher’s preoccupation with his “inner white girl,” that is, the undue influence on his own music of that by “white-girl” singer-songwriters like Phair, Joni Mitchell, and Tori Amos because of the freedom these artists represent, as opposed to his own hang-ups as a gay, Black boy in thrall to his mother.

Usher, a red tunic-wearing usher at Disney’s The Lion King—frequently alluded to when names like Mufasa, Nala, Rafiki, Sarabi, and Scar are attributed to his family members—is a Detroit-raised songwriter living in New York with a big-time student debt. He’s struggling to create a “big, Black and queer-ass Broadway show” that avoids the compromises a Black artist, who wants to write something “unapologetically Black” has to make to appeal to white audiences, critics, and backers.

At one point, he’ll be forced by necessity to compromise when he’s asked to ghostwrite a gospel play on behalf of moviemaker Tyler Perry, whose work his family adores (because he writes about “real life,” they insist), but which Usher despises as “crap” and “hack buffoonery.” Much of the show’s rich humor comes from how certain characters in Usher’s life parody the broadly stereotypical Tyler style.

Usher feels worthless because, while “starved for Black affirmation and affection,” he’s unable to find a suitable Black partner; his hookups are mainly white, like the meth-using, Inwood guy who does it to him from behind. It’s a raunchy scene, tinged with pathos, reminiscent of an even funnier one in Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song Trilogy.

He suffers from the towering guilt of having been raised by God-fearing people (including his scripture-spouting mother), who reject his “homosexsh’alities,” worry over his sinful life, and reject his artistic aspirations. He also can’t avoid reminders of a friend who died of AIDS and ponders if he can possibly change or is just “stuck with who I am.”

A Strange Loop explores his anxieties in what the script calls “Daily Self-Loathings” by representing them as an ensemble of six singing, dancing, and acting Thoughts. It’s hard not to feel that the play is a therapeutic exercise designed to exorcize Jackson’s demons. The Thoughts are performed by the ultra-versatile team of L. Morgan Lee (a transgender performer who identifies as “she” and “her”), James Jackson, Jr., John-Michael Lyles, John-Andrew Morrison, Jason Veasey, and Antwayn Hopper. All are back from the Off-Broadway production. Casting offices rarely get noticed in reviews, but those responsible for creating this amazingly gifted ensemble deserve a loud shout-out, so here’s to The Telsey Office/Destiny Lilly, CSA & Alaine Alldaffer, for going above and beyond the call of duty.

Each—helped by Montana Levi Blanco’s many costumes (many redesigned for Broadway)—takes on two or more caricaturish roles, including Usher’s pious mother and alcoholic father, an imaginary Mr. Right he meets on the subway, a doctor, an agent, and a lover. There are also fanciful appearances by such Black luminaries as Harriet Tubman, Carter G. Woodson, James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, and others, even “Twelve Years a Slave.”

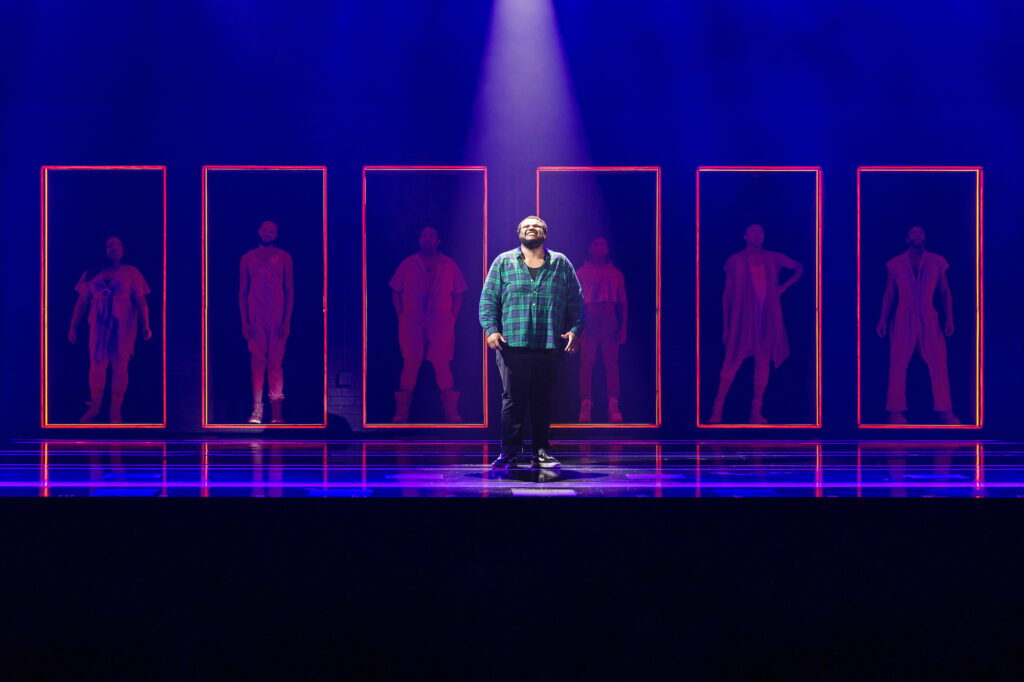

Usher and his Thoughts sing and dance his problems in a highly theatricalized format creatively staged by Stephen Brackett and vividly choreographed by Raja Feather Kelly. Arnulfo Maldonado’s set, flashily lit by Jen Schriever, makes use of door-sized, neon-outlined cubicles that are either placed upstage next to one another or sent to opposite sides of the stage.

Toward the end there’s a surprising, if not absolutely necessary, scenic shift to Usher’s parents’ more naturalistic, overcrowded home, with a church setting directly overhead. Usher now takes on the role of a fiery pastor (of the Quasi-Africana Church of God in Christ), castigating gays by declaring AIDS to be God’s punishment for their transgressions.

The music is heavily rhythmic; the lyrics emotionally expressive, didactically inclined, and narratively thin; the language often filthy (anal sex and fellatio, less delicately expressed, get the lion’s share); the “n-words” and “fag” references endemic; and the familiar African-American allusions common.

A Strange Loop is highly polished, and Jaquel Spivey, taking on the role created by Larry Owens, defines the term tour-de-force by his exceptional acting and singing. Because of its treatment of Black, gay identity, this is the kind of play that will provoke reams of socio-political discussion by those more qualified to discuss it than I.

Regardless of how well directed, designed, and performed A Strange Loop is, or how often it inserts woke references (like vers bottom, intersectionality, code-switching, second-wave feminism, and so forth), it eventually gets a bit preachy, repeating its themes a tad too persistently. But at a zippy hour and 45 uninterrupted minutes this can be forgiven in the face of so much unforgettable talent.

Note: This review is adapted from the one I wrote of the original production for “Theatre’s Leiter Side.”

A Strange Loop. Open Run at the Lyceum Theatre (149 West 45th Street, between Sixth and Seventh Avenues). One hour 40 minutes, no intermission. www.strangeloopmusical.com

Photos: Marc J. Franklin