Lucian Msamati

by Carol Rocamora,

Is talent divinely given? If so, what bargain do you have to make with God to get it?

That’s the tantalizing question that drives Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus (1979), now streaming on NT Live in a sensational production directed by Michael Longhurst (2016).

Shaffer seizes upon an obscure historical theory concerning the 18th century Italian-born composer, Antonio Salieri (1750-1825), who was rumored to have poisoned the young genius Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791). Though the rumor was never substantiated, it’s a fabulous dramatic idea, and Shaffer has made the most of it. His Salieri is Court Composer to Joseph II in Vienna in the late 1700s when music was the center of the Court culture. He’s a mediocre talent with king-sized ambitions. “I wanted fame,” Salieri explains in the play’s prologue, as he looks back on his life during his final hour. “I wanted to blaze like a comet in one special way: music. Music is God’s art.”

So he makes a pact with God to lead a pious, virtuous life, in return for talent and celebrity. Things seem to be going swimmingly (he’s a celebrated composer, performed throughout Vienna, a favorite of the Emperor, adored by his pupils) – that is, until a young upstart arrives in town and turns his world upside down. Once Salieri hears his music, he knows he’s in the presence of genius. “It seemed to me that I had heard the voice of God … through the voice of an obscene child.”

Adam Gillen

That “obscene child,” is, of course, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. “Was it then I began to have thoughts of murder?” asks Salieri. The rest of the plot dramatizes how Salieri, obsessed with jealousy and envy, attempts to ruin Mozart as the latter infuses Vienna and the Court with his sublime music. “God did this to me!” Salieri cries, enraged at the betrayal. “I had to stop Mozart…but how?” Salieri succeeds, blocking Mozart’s opportunities, undermining his reputation as a composer, damning him with faint praise, etc. Mozart dies penniless, buried in an unmarked common grave.

The brilliance of Shaffer’s play lies in its structure and commanding characters. Salieri narrates the story as a series of flashbacks, while sitting in his wheelchair, waiting to die. Lucian Msamati, who embodies this formidable role, rules the stage with his larger-than-life presence, playing the anti-hero with Lucifer-like charisma. He’s full of dangerous complexities – virtuous yet ruthless, monogamous yet lascivious, charming yet devious, reserved yet indulgent (he’s addicted to sweets, especially his favorite Brandy-laced “nipples of Venus.”) Adam Gillen plays Mozart as a flamboyant, hyperactive, foul-mouthed adolescent – offensive yet irresistible. Brilliantly costumed by Chloe Lamford in neon pink and yellow, he dashes about the stage, cavorting, jumping on top of the piano, playing while standing on the bench. You can’t take your eyes off him.

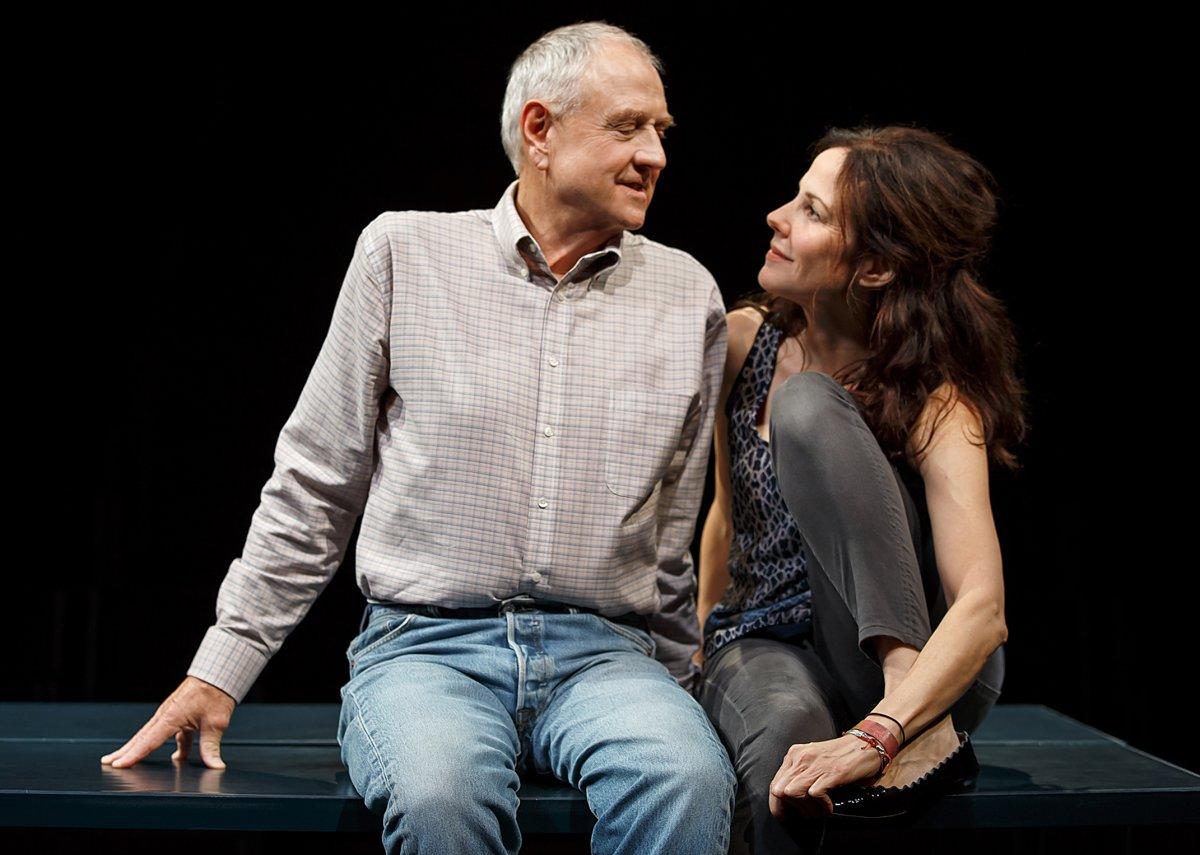

Karla Crome, Adam Gillen

Those of you who saw the marvelous 1984 film version may wonder how a revival might enhance the appreciation of this celebrated play. The answer is: thrilling theatricality. Longhurst has placed an orchestra – yes, an entire 20-piece orchestra (Southbank Sinfonia) – onstage, and integrated its members into the action. They not only play Mozart’s sublime music – they also serve as a Greek Chorus, moving about the stage, following the action, emoting along with the characters. They perform excerpts of The Marriage of Figaro (the first opera Mozart composed while in Court), as well as moments from Don Giovanni and the celestial quartet from Cosi fan tutte, sung by marvelous opera singers. Chloe Lamford’s spectacular set in the RNT’s Olivier Theatre features a central orchestra pit, with an upstage platform where Joseph II (an amusing Tom Edden) is seated, watching the opera singers on a downstage semi-circular platform. (There are also notable performances by Karla Crome as Mozart’s feisty wife Constanze, and Salieri’s co-narrators, Sarah Amankwah and Hammed Animashaun.) So we’re given a lavish spectacle – a triple treat of theatre, opera, and some of the most sublime choral music ever written.

The latter is sung in the penultimate scene, while the dying Mozart composes his last work – the unfinished Requiem. It is at that moment when Salieri experiences his final epiphany. “In ten years of unrelenting spite, I had destroyed myself.”

According to playwright Shaffer, in this fascinating study of envy and its deadly consequences, God has the last laugh. Salieri, who recognizes his own mediocrity in “God’s art,” lives 32 more years to become “the most famous musician in Europe. That was my sentence. I’m going to be immortal after all.” In the play’s last moment, he writes his own epitaph: “Antonio Salieri – patron saint of mediocrities. You can pray for me and I will forgive you. Mediocrities – I absolve you all!”

Amadeus, by Peter Shaffer, directed by Michael Longhurst, at the Royal National Theatre (2016), streaming on NT Live through July 22.