by Harry Haun

A spellbinding, finger-snapping, sensuous “Fever” is what led Cady Huffman to Peggy Lee in the first place. “It really struck me as I was growing up,” she recalls. “I remember thinking, ‘Wow! What is that song? It’s so simple and so sexy, so tough and so fragile—all at the same time, like so much in life.”

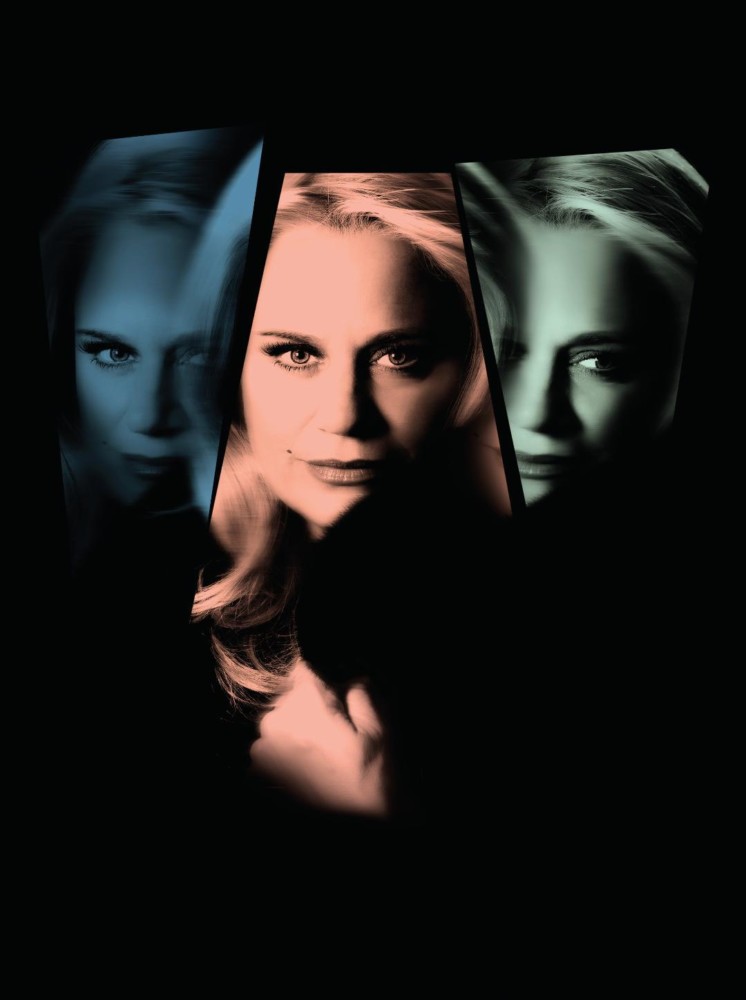

And as fevers go, this particular one has yet to lift. If anything, it will lift Huffman straight onto the stage of Yotel’s new nightspot, The Green Room 42, to present Miss Peggy Lee: In Her Own Words and Music June 10 and 12. It’s a theater piece parading (at present) as cabaret, co-written by Huffman and her director, Will Nunziata, to celebrate the songsmith skills of Lee, who toiled as a lyricist or as a composer and, on special occasions, as both.

“Fever,” let it hastily be added, is not a Lee original, although she did sprinkle a few uncopyrighted words (“Romeo loved Juliet,” “Captain Smith and Pocahontas”) to the existing ditty by Eddie Cooley and John Davenport. Similarly, her classic query–“Is That All There Is?”—was written by Mike Stoller and Jerry Leiber specifically for Marlene Dietrich, but Dietrich found it so despairing she passed on it and left it to Lee to take it to a Grammy win.

These and other smash Peggy Lee recordings–“Lover,” “Golden Earrings,” “Big Spender,” et al—take a backseat in this presentation of her own tunes. “It’s important for us to mention the hits because we know people are going to want to hear them,” allows Nunziata, “but we’re not doing them in full. “We’re really just looking at the songs she wrote. They’re the words that made up part of our libretto. The premise is that Peggy Lee returns in 2019 for a reason, and one of the reasons is in her own voice–unapologetically.”

“Eventually,” adds Huffman, “we want this to be a full-blown theatrical piece. We’re not approaching it as a tribute or a revue. I’m not imitating Peggy Lee. We’re trying to tell her story in the vein of Lady Day or Patsy Cline. If she came back and saw what’s going on right now, what would she say?”

Before taking on this project (which hopefully will be ready next year for Lee’s centenary), she and Nunziata secured the blessings–along with some insightful, telltale personal observations–of Lee’s granddaughter, Holly.

“I think what surprised me the most from what I learned from Holly was Peggy’s spirituality,” the actress admits. “She was kidded for lighting candles and praying and espousing certain things at a time when people weren’t doing that so much. I believe she’d bring her spiritual side to greeting a modern audience. She was all about kindness, forgiveness and the struggle to be human. That’s what comes across in her very truthful lyrics.”

Nunziata did the bulk of the show’s research, she insists. “I didn’t consume the books the way Will did, but I did catch a radio documentary about her that really intrigued me. It got me to realizing ‘This was a woman who didn’t have it easy,’ and that helped me as a young artist to understand that this is the human reality. We all have struggles, no matter how bad they are.”

The seventh of eight children, Lee was the one who started singing through early hardships. Later in life, this produced songs of wide emotive range. “The way it’s been evolving,” says Huffman, “is that music tells a lot of the story. Peggy even said, ‘I like to write happy music when I’m sad and sad music when I’m happy.’ That makes it an easy way to tell a story, doesn’t it?”

At the outset, she was Norma Delores Egstrom in Jamestown, North Dakota, and turned “professional” singer at 14–for 50 cents a pop at local PTA meetings. Three years later she traveled 100 miles to Fargo to do a radio show and was officially christened Peggy Lee by the program director there.

At first, music was a means of escaping a cruel stepmother. Then it got her into four brief but abusive marriages—two musicians (Dave Barbour and Jack Del Rio) flanking two actors (Brad Dexter and Dewey Martin). Barbour was the pick of the litter and love of her life. They met as members of the Benny Goodman band and fell in love despite Goodman’s edict not to fraternize with the girl singer. Barbour got fired for it and Lee quit in protest. They produced a daughter, Nicki, and some of the most popular songs of the period—“It’s a Good Day (for Singin’ a Song),” “Manana (Is Soon Enough for Me)” and “I Don’t Know Enough About You.” In 1965, after 13 years of sobriety, he decided to remarry her but died four days before the wedding.

Tours and TV constituted most of Lee’s career. In films, she sang with the Goodman band in two 1943 features, Stage Door Canteen and The Powers Girl, and did an ill-advised 1952 redo of The Jazz Singer with Danny Thomas. 1955 was her banner year in movies. She was memorable, and Oscar-nominated, in Pete Kelly’s Blues in a role she could almost do by rote—the boozy, abused blues singer who winds up with a rag doll in the funny farm.

Also that year, she contributed six sets of lyrics to the music of Oliver Wallace for Walt Disney’s animated feature, Lady and the Tramp. For that, she received $1,000—plus another $3,500 for voicing four characters: two cats (“Si” and “Am”), a Pekingese and a human. In November 1988, when that film rang up $90 million in videocassette sales, she sued and, three years later, won $2.3 million against Disney to recoup royalties owed her.

A Tony nominee as Ziegfeld’s favorite in The Will Rogers Follies and a Tony winner as Bialystok & Bloom’s secretary in The Producers, Huffman has as much to act as to sing. “On stage, she wasn’t all that comfortable performing. That discomfort of being in front of everybody—the hair-and-makeup ordeals you must go through to get out there—kept audiences at a distance. Off-stage, she loved to communicate—one on one—with them, and a big part of what she wanted to communicate is the love and connection between people. That’s the real person we want to bring on stage with us.”