By Ron Fassler . . .

Now playing at the Irish Rep, Chester Bailey is a play for our times. In our current and far too disturbing climate, we observe daily how denialism is thwarting common sense in the psyches of many Americans. We are a nation at war with the truth, and yet for those true believers, what they feel is all too real. Even though Joseph Dougherty’s inquisitive new play is set in 1945 just after the end of World War II, its title character is as self-deluded as those Japanese soldiers, it has been said, kept fighting long after their Emperor conceded defeat.

In its six-year journey, Chester Bailey has received prior productions in San Francisco, California, Shepherdstown, West Virginia, and Barrington, Massachusetts. For its New York premiere, Reed Birney and Ephraim Birney, comprise its two-person cast, as they did in the play’s two prior productions. In the roles of doctor and patient, their blood bond feeds the story’s soul in exceptional fashion. The elder Birney, long one of the finest actors of his generation, is matched every step of the way by his twenty-six-year-old son, in the early stages of a stage career with limitless potential. If that sounds exciting, believe me, it is.

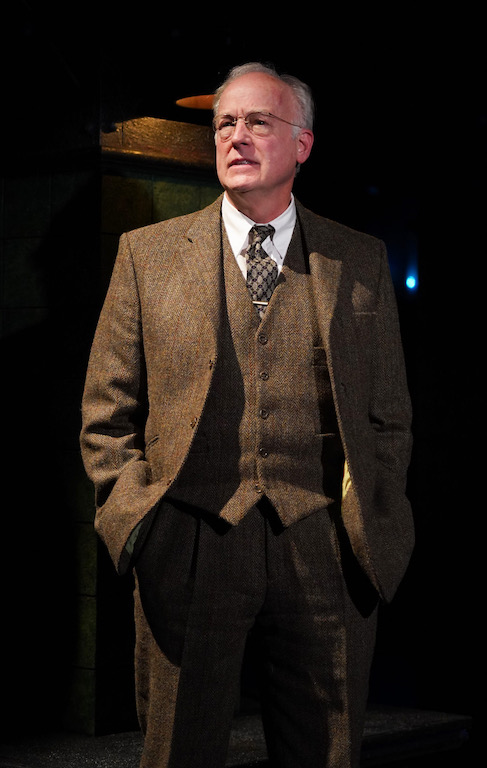

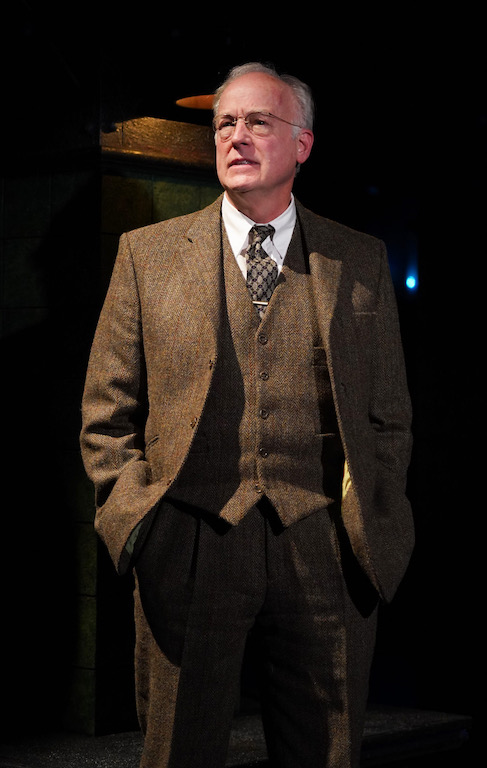

At the start, the single set is that of an uninviting hospital room at a Long Island mental hospital (exquisitely designed by John Lee Beatty). It is here twenty-three-year-old Chester Bailey is recovering from devastating injuries incurred during World War II, but not as a result of miliary service. His parents, having once suffered the early death of a daughter, manage to find their remaining child a job at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, ostensibly to keep him safe from wartime service. Tragically, in a bizarre attack by a co-worker afflicted with syphilis, Chester is left blinded and handless. Dr. Philip Cotton, a seemingly well-put together psychiatrist in a brown three-piece wool suit, is given the assignment of trying to decipher why the young man insists he can both see and do anything he wants physically, even though he possesses neither eyes nor hands. The power of denial leads Dr. Cotton to question his own psyche, as he so aptly states “If there’s one thing reality can’t tolerate, it’s competition.”

In its first twenty minutes, alternating monologues structure a back and forth between protagonist and antagonist that test the patience of its audience. But once the characters confront one another in superb dialogue, the play crackles with tension; its plot revelations revealed slowly and methodically towards shattering results. Clearly a role model is that of 1975’s Equus, Peter Shaffer’s Tony Award-winning Best Play, which dealt similarly with a doctor/patient relationship in which the elder envies the younger’s passionate intensity to dwell in a private world built to pacify their inner torment. But Chester Bailey is so much more than a “physician heal thyself” story. And in the hands of its two actors, under the sensitive direction and finely tuned staging of Ron Lagomarsino, the riveting drama unfolds with painful clarity.

Brian MacDevitt’s somber lighting sweeps the stage with precision every step of the way. And though there are only two costumes, Toni-Leslie James has rendered them in splendid detail. Brendan Aanes sound design is perfection, from soft and disturbing noises from afar to lilting music emanating from a nearby radio. And again, enough can’t be said of Beatty’s set, with it hinting at so many things germane to the play: a battleship, the old Penn Station, and that of its central area, a dark and foreboding hospital room.

Reed Birney’s Dr. Cotton offers a richness of intellect and compassion that infuses every inch of the character. He is an actor so comfortable on stage one hopes a role or two in the classical cannon, say Chekhov or Ibsen, are still in his sights before calling it a day. Ephraim Birney, saddled with a part that requires so much of him emotionally and physically, confidentially risks daring to go to the dark places required. And we are the ones rewarded for his efforts.

This is that rare occasion where real life (embodied in a faultless father-son acting team) illuminates that of its play’s subjects with the intensity of a white-hot light. Though the character of Chester Bailey can never be made whole again, the power of his situation, embodied in Joseph Doughtery’s thoughtful and provoking play, is a complete experience.

Chester Bailey is at the Irish Rep, 132 W 22nd Street, NYC 10036 now through November 20th. For ticket information, please visit www.irishrep.org

Photos: Carol Rosegg