JOHN LEE BEATTY, PORTRAIT OF THE DESIGNER AS A YOUNG MAN: A LOST INTERVIEW

Part 7: “Realist Extraordinaire”

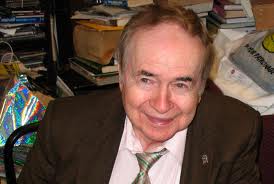

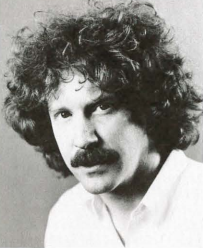

John Lee Beatty

As told to Samuel L. Leiter

This is the seventh installment in my previously unpublished 1980 interview with designer John Lee Beatty, which is being serialized in Theater Pizzazz. Please see Part 1 for an introduction to the interview, which I’ve adapted as a narrative, and why it’s first being published 40 years after it occurred.

I suppose I may have offended some people in my innocence. One agent, Robert Lantz, told me to stop by and see him sometime but it never occurred to me that he might want to represent me. I just thought he meant to stop by and see him sometime. So, one day, I stopped by and said, “Hi, how are you?” and then I turned around and left. I never mentioned him representing me and I’m sure he thought I was as rude as can be but it never occurred to me that he’d want to represent me. It did later; now I can see why. But then, no.

I have an agent now. I’m with William Morris, Ed Robbins. William Morris was such an implausible choice for me. People expected some sort of Off-Broadway type but I thought that the combination of any sort of youthful “Off-Broadwayness” and William Morris’s sort of establishment image might be positive. [Note: John Lee says that when Robbins retired he was moved over to his assistant, Peter Hagan, with whom he continues today, although at different agencies through the years. Hagan does all of his contracts, including regional.]

Truthfully, I don’t think an agent’s terribly important to a designer. They don’t get you work. They got me one job, the first job after I’d joined them, and it turned out to be the worst job I’d ever had. I have to pay the 10 percent to the agency for all my jobs.

Set Design – Talley’s Folly

However, I was doing so much regional theatre that I finally arranged for the regional theatre jobs to be at my discretion as to whether the agency would be involved in the contracts because so many regional theaters contract you on a flat rate. It’s the same for every designer. There’s no reason to give them 10 percent for something they don’t negotiate. And, obviously, not for my things at Circle Rep, where you’re lucky to get paid, period. Let alone the quantity of the payment.

I came here in the fall of 1973 and had my first Broadway show in 1976. I wanted to make it to Broadway by 25; I didn’t. But 27 isn’t bad. I’m working now on my ninth Broadway show, Talley’s Folly. I do regional, I still do Off-Off, I still do shows at Circle Rep, I still do shows at Manhattan Theatre Club. I find I still love plays. I’m in love with plays, in fact. I like the writing to be good.

I have done musicals as well as straight plays, of course. As I said earlier, I had grown up seeing musicals so I wanted to be a musical designer. And everything I did looked like Oliver Smith for the longest time. I was so amused to become the realistic designer of Off-Off Broadway, or Off Broadway, and then the Shakespeare Festival and places. They called me “realist extraordinaire.” That was the furthest thing from my mind. I don’t think I’m a realistic designer at all. It’s very “designed” work. I think I’m pretty mainstream, quite frankly.

People say “Mielziner” to me sometimes, which is very flattering. It’s a real actors’ and directors’ type of scenery. You can see where my priorities are. I’m not terribly into these great displays or anything. You notice my sets; they’re not that self-effacing. A little self-effacing, but not a lot. I think my strongest suit as a designer is that I very seldom get the wrong mood. I think that’s why I don’t disappoint too badly with directors.

I may not be great on every little part of something (you never can be) but I don’t think I miss the tone of something too badly. If I do, I feel it. Believe me, my greatest pain is if I’ve missed the tone of the proceedings. And I know the shows I’ve missed.

(To be continued.)