By Eric J. Grimm

Herman Hesse’s 1922 novel Siddhartha may not seem at first glance to be a prime candidate for an Italian pop-rock opera treatment, but it is perhaps more surprising that it had not already inspired a musical in many languages. Hesse wrote Siddhartha, the story of a Brahmin’s son’s self-discovery in India, in his native German language. The novel did not receive worldwide recognition until after Hesse’s death in 1962. Siddhartha’s journey of coming to love the world in its totality resonates the world over and, given its setting, is ideal for a musical adaptation.

Isabella Biffi’s musical was originally workshopped in Milan’s Opera Jail, a maximum-security prison. The Italian tradition of using the performing arts as a mode of rehabilitation was brilliantly explored in the Taviani Brothers’ 2012 documentary-narrative hybrid film Caesar Must Die. Siddhartha’s discovery that enlightenment can only be achieved through personal experience and self-reflection seems appropriate for the prisoners involved in the production, some of whom were serving life sentences. The musical then transferred to a theater in Milan where a professional production was mounted. The version that played at Manhattan’s 54 Below was a truncated concert featuring six primary cast members from a company of twenty-four. In this version the music is sung in Italian while a narrator who doubles as Siddhartha’s companion Govinda guides the audience through the plot in English. The music is modern Italian pop with a bit of traditional Indian music sprinkled throughout.

Biffi and crew have taken some liberties with Hesse’s text. Siddhartha is described as a prince where in the novel he is the son of a Brahmin, a caste of priests. This becomes a troublesome change when Siddhartha unexpectedly embraces a lavish lifestyle later in his life. The musical adds an additional female character who is pregnant with Siddhartha’s son when he leaves on his journey, perhaps because Hesse’s story has only one female character. The relationship between Siddhartha and courtesan Kamala is played for high melodrama, suggesting a torrid love affair where the book makes clear that Siddhartha cannot experience romantic love. Despite the changes, the musical generally conveys the essential elements of Hesse’s story. As in the novel, Siddhartha sheds himself of all luxuries and personal attachments in order to achieve the highest enlightenment.

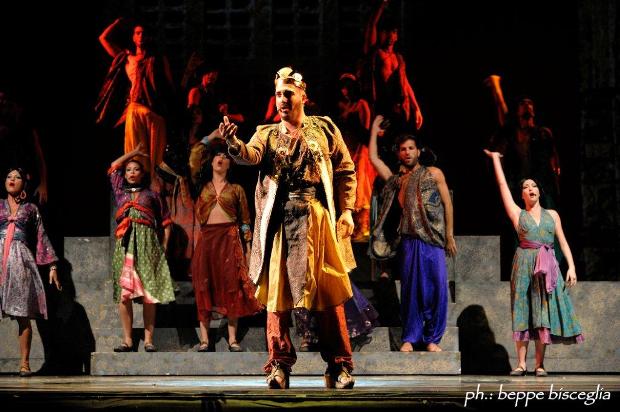

The great joy of Siddhartha: The Musical is its performers. All six have crisp and pleasing pop voices that convey a yearning for worldly understanding that eludes the characters for most of the show. Giorgio Adamo, sporting long brown hair and an appropriate look of angst on his face throughout, plays Siddhartha with an intensity that balances out the beautiful clarity of his singing voice. Paolo Gatti as Siddhartha’s father has the most distinct voice: a rich bass that commands authority. The standout of the group is Katy Desario, so seductive and fragile as Kamala. By trading in the indifference and cool nature of Hesse’s character for a more traditional hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold, the show gives way for Desario to wail her lament when Siddhartha leaves her for a more solitary, contemplative life. Her vocals are precise, though not so rigid to disguise her heartache. She easily commanded the most applause.

Though television screens showed footage of an elaborate full production that toured throughout Italy, a concert version is an ideal way to take in these performers. Their well-trained voices and commitment to their characters, who are somewhat thinly constructed in both the Hesse novel and the musical adaptation, play well in an intimate setting. That said, this showcase of highlights shows promise for a fully staged show with great roles for talented musical theater performers.