By Samuel L. Leiter

Looking back on the season of 1921-1922, for which we’ve already surveyed selected plays and musicals, brings us next to a slew of revues. These continued to emulate, albeit in a more formal and, often, visually elaborate, context, the potpourri of comedic and musical numbers associated with vaudeville. Around 14 of the season’s shows could be counted as revue, even a few possessing the semblance of a plot.

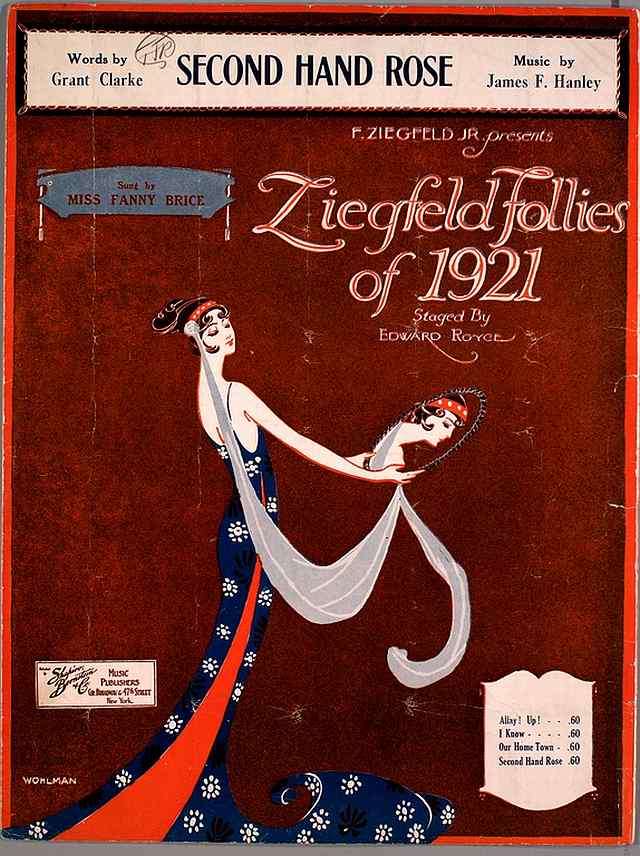

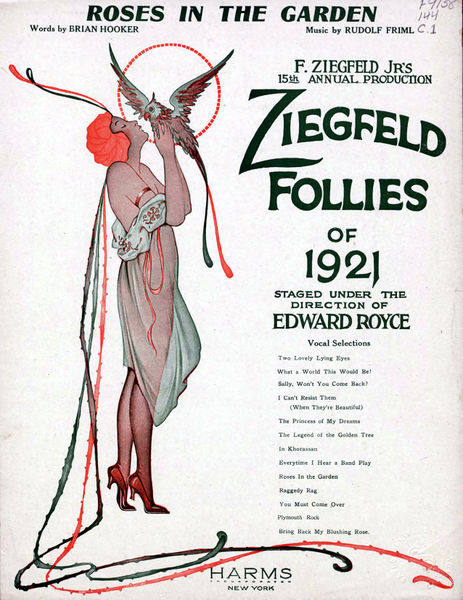

No sooner had the new season begun in June, then the Ziegfeld Follies of 1921 arrived (Globe Theatre, 6/2/21, 119) although it brought only a modicum of glory to Flo Ziegfeld’s fabled annual series. This edition’s 29 scenes met with mixed reviews, some declaring the show terrific, others considering it under par. It was crowded with “riots of color in settings and costumes, luxurious silks and satins, the best-looking chorus of this or any other year, some remarkable dancing, a dash of fair-to-middling singing, considerable comedy and an undefinable something that must simply be set down as tone,” raved the Times. Stars Fannie Brice and W.C. Fields were among those who helped Ziegfeld lavish over a quarter of a million dollars on the work.

Comedy bits included a takeoff on Camille with Brice, Fields, and Raymond Hitchcock playing Barrymore understudies; a farcical boxing match between Brice as Georges Carpentier and Ray Dooley as Jack Dempsey; Brice as a Scotch maid with a Yiddish accent; Fields doing an early version of his “Professor” character; and Charles O’Donnell in a vaudeville number called “The Piano Tuner.”

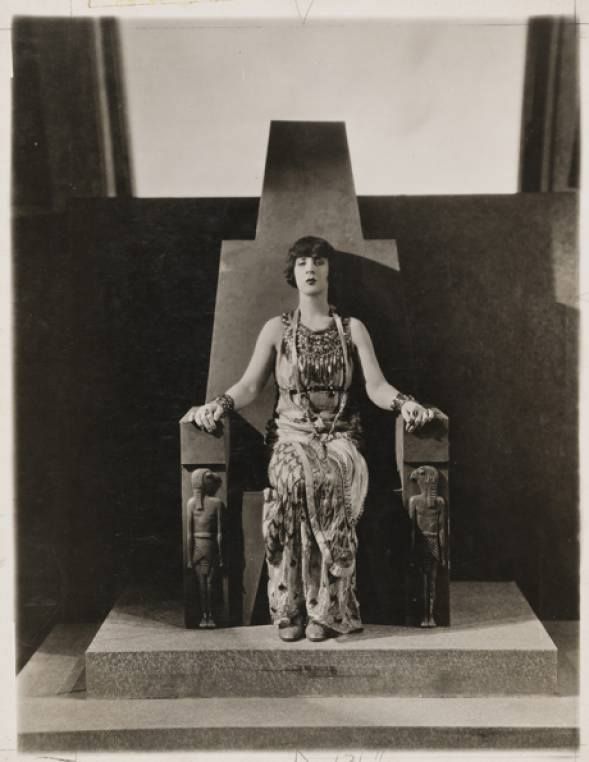

Ava Land, Ziegfeld Follies 1921

The tableaux and spectacles, arranged by the creative Ben-Ali Haggin, included a memorable one showing Prohibition standing before a Statue of Liberty background. Dancer Florence O’Denishawn (“with her early bare body flashing in the light,” ogled the Times) was a knockout, as were Parisian dancers Germaine Mitti and M. Tillio of the Folies Bergere.

Standout songs included Grant Clarke and James Hanley’s “Second Hand Rose,” which became a Brice specialty, and Channing Pollock and Maurice Yvain’s English version of the French “Mon Homme,” known here as “My Man.” Both became iconic Brice numbers. The latter was staged as an Apache scene that revealed a tragic side of the comic star that took her fans by surprise.

A month later, one of Ziegfeld’s greatest rivals, George White produced the third edition of his series, George White’s Scandals of 1921 (Liberty Theatre, 7/11/22, 97), considered an improvement over its predecessors. It was congratulated on the color and realism of its spectacle, the novelty and style of its costumes, and the performing talents of its contributors. Many of the show’s 20 scenes were set in New York, but locales as far flung as the South Seas, Russia’s Winter Palace, the Panama Canal, the North Pole, the Flying Dutchman, and biblical times, were also seen. In the latter, Samson (Lester Allen) and Delilah (Ann Pennington) made their appearance, although the Herald thought Pennington, one of eras’ top dancing stars, was getting “chubby.”

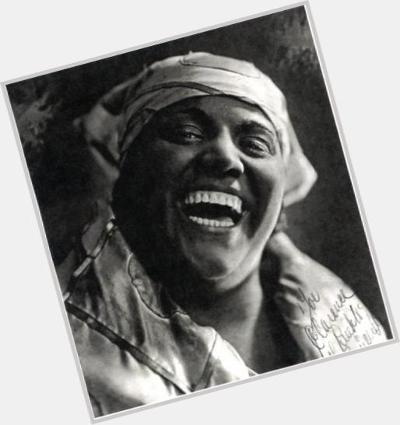

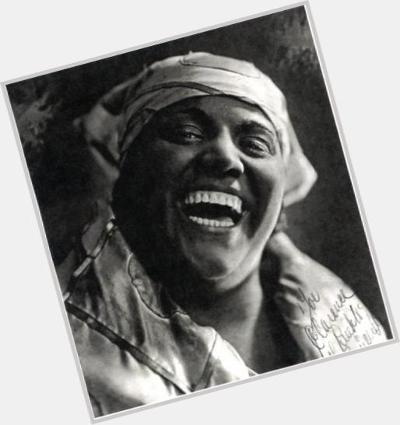

The material was an assortment of dances, sketches, and George Gershwin songs, the general intent being to spoof the past year’s events. “The satire,” sighed the Times, “does not go very far or very deep.” Although now and then effective, the humor too often seemed forced, flat, and unsubtle, even in the hands of comics Lester Allen, George Bickel, and George Le Maire. Sharing the stage was the black mammy entertainer Teresa Gardela, with her “Aunt Jemima” act of plantation songs: the Times cited her as the evening’s standout. Black-face singer-comic Lou Holz was on board as well. Yes, times have changed!

Teresa (Tess) Gardela – Aunt Jemima

Two weeks after The Mimic World (Century Roof, 8/15/21, 27) bombed, the curtain rose on the third edition of one of the top revue series, The Greenwich Village Follies of 1921 (Shubert Theatre, 8/31/21, 167). This was on Broadway, not Greenwich Village, like its earlier versions. This shift to the Great White Way, thought Arthur Hornblow, meant the show “lost whatever advantage the village cachet and their isolation downtown gave them.” Now the show had to compete next to its big time rivals.

The GVM was a succession of specialty acts, mixed with a parade of gorgeously dressed beauties in tableaux. John Murray Anderson’s tasteful stage arrangements, the masks of Benda, and the use of lovely lighting were combined with memorable results. “Nothing more beautiful than the color effects has been seen on the New York stage in years,” clapped Charles Pike Sawyer. Production numbers like “When Dreams Come True,” “Snowflakes,” and “In Silver and Black” were highly praised, particularly the latter in its Art Nouveau Aubrey Beardsley styling.

One routine revealed beauty Florence Normand wearing formfitting black tights; another presented her “entirely nude except for some gilded leaves discreetly arranged,” noted Hornblow. Irene Franklin and Rosalinde Fuller were singers who gifted the show with musical grace.

Music Box Revue 1922

Following Get Together (Hippodrome, September 3, 397), at the city’s largest theatre (6,000 seats), in which premier dancers Michael Fokine and Vera Fokina mingled with elephants, juggling bulldogs, and crow named Jocko, came the first of what would be four Music Box Revue productions. It was notable for inaugurating Sam H. Harris and Irving Berlin’s exquisite new Music Box Theatre (9/22/21, 440), for whose opening dignified ushers in white satin knickers escorted patrons to their seats.

This first edition was a resplendent package that bowled over critics like Hornblow, who was stunned by “such ravishingly beautiful tableaux, such gorgeous costuming, such a wealth of comedy and spectacular freshness, such a piling up of Pelion on Osa of everything that’s decorative, dazzling, harmonious, intoxicatingly beautiful in the theatre.”

Alexander Woollcott had no difficulty picking Berlin’s “Say it with Music,” sung by Paul Frawley and Wilda Bennett, as the hit of the event (it became the official anthem of the series). Another well-liked Berlin number was the ragtime “Everybody Step,” sung by the Brox Sisters.

Hassard Short did an exceptional job of staging the $188,000 smash hit. Leading comics Willie Collier and Sam Bernard convulsed the house, as did comedienne Florence Moore. Satirical sketches included “Under the Bed,” a spoof of bedroom farces featuring Moore, and “Nothing but Cuts,” with Collier and Bernard discussing the principles of playwriting.

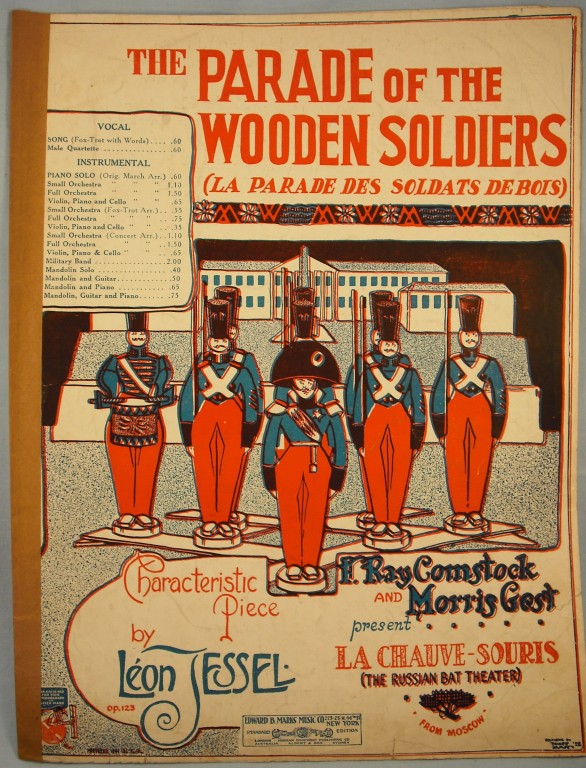

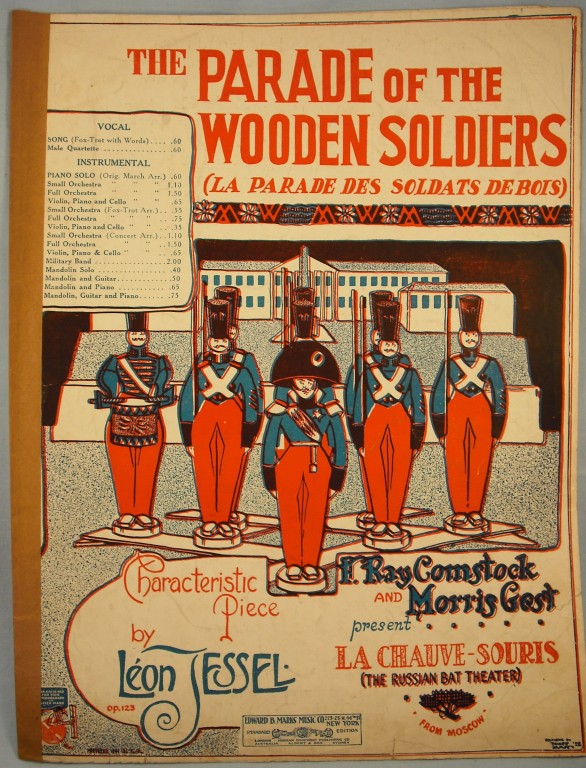

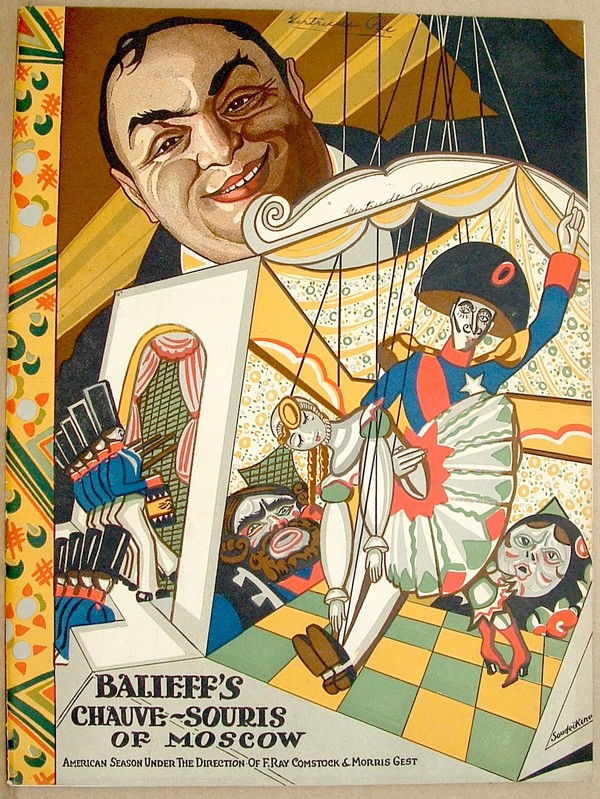

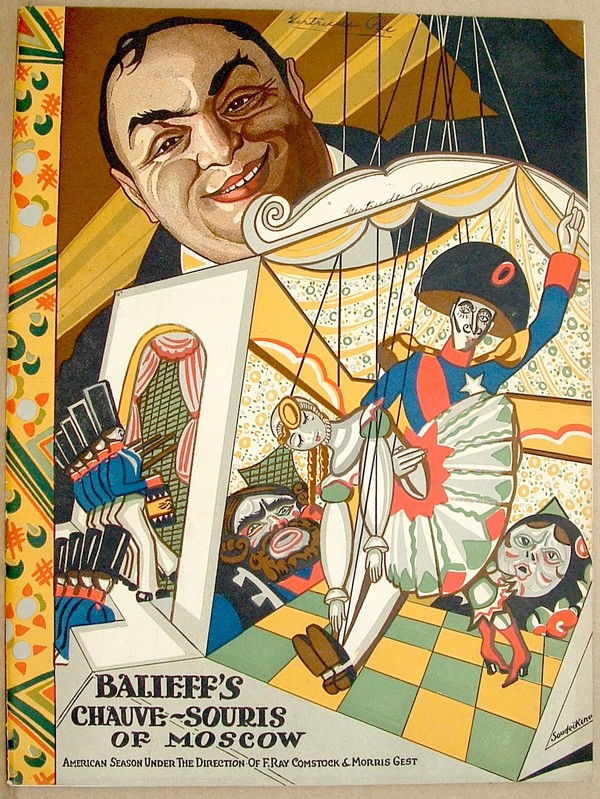

Bombo (Jolson’s Fifty-ninth Street Theatre, 10/6/21, 218) was mainly a happy showcase for blackface singer Al Jolson, one of the era’s greatest stars, just as The Perfect Fool (George M. Cohan Theatre, 11/2/21, 275), soon after, was for silly comedian Ed Wynn. Less notable, despite a few bright spots, were Elsie Janis and Her Gang (Gaiety Theatre, January 16, 1922, 56), and Pins and Needles (Shubert Theatre, February 1, 1922, 46). But then came the big splash made by Le Chauve Souris, a groundbreaking Russian-language show (its Russian title was Letuchaya Muish) directed by Nikita Balieff. It would produce several editions into the 1940s.

Le Chauve-Souris was born in Moscow over a dozen years earlier, when various entertainers would gather at Balieff’s Bat Restaurant after hours and put on shows for their own amusement. These evolved into regular public entertainments until scattered by the Russian Revolution, many of those involved fleeing to Paris, where Balieff began reorganizing them for a local audience that loved them and gave them the French name for “The Bat.” Finally, they were brought to New York and became a sensation.

The first edition offered 13 numbers of varying quality. The rotund Balieff served as MC, his struggles with English contributing greatly to the fun. “Balieff is an extraordinary comedian, Balieff is an uncompromising regisseur, and Balieff brings us the ruddy rejuvenating warmth of the peasant where is most the peasant,” wrote Kenneth Macgowan.

Program Cover U.S. Tour 1922

The best-appreciated piece was “The Parade of the Wooden Soldiers,” a precision dance in which wooden toys come to life.” Also delightful were the Katinka, a polka, and the Chastoushki, a medley of folk work songs. The original long run, which stretched into early 1923 (when one performance hosted the visiting Moscow Art Theatre), was divided into four editions, the latter three in the Century Theatre’s rooftop playhouse, designed in a blaze of Russian colors, with new material added while the Katinka and Chastoushki remained, until, in 1923, the former was dropped.

One other topnotch revue delighted audiences this season, Make it Snappy (Winter Garden, 4/13/22, 96), starring Eddie Cantor, one of the foremost singer-comedians, despite being prone to blackface romping. Unfortunately, space concerns preclude its description here, but there’s little to regret about passing by two other revues of 1921-1922, Frank Fay’s Fables (Park Theatre, 2/26/22, 32), and Some Party (Jolson’s Fifty-ninth Street Theatre, 4/15/22, 17).

One group remains in our look back at 1921-1922—the revivals. Apart from something in Italian and some Shakespeare from Fritz Leiber’s touring troupe, New York saw a dozen dramatic revivals, most from the past half century. Modern classics by Ibsen, Shaw, and Wilde mingled with more ephemeral work by such as Belasco, Royle, and Walter. Only an eighteenth-century comedy by Sheridan offered a classical contrast. The pickings may have been slim but, as we’ll see next week, not without interest.