Theater Review by Samuel L. Leiter . . . .

It’s always a pleasure to anticipate whatever popular playwright-drag artist-actor Charles Busch is cooking up for his next comedic endeavor. Only rarely is one disappointed; to a limited degree that’s true as well of his latest, Ibsen’s Ghost: An Irresponsible Biographical Fantasy, whose subtitle is actually cited in this intermittently amusing literary farce.

Busch’s mixture of historical fact and humorous fabrication, centering on Suzannah Ibsen (Busch), the recently widowed wife of playwriting giant, Henrik, is a triumphant example of fast-paced, energized high-camp acting rising above material that, in other hands, could be a dreary dud. For a contrast between mastery and mayhem in these matters, a comparison of Ibsen’s Ghost with Deadly Stages, across town, offers a casebook example.

Premiered earlier this year at New Brunswick’s George Street Playhouse, Ibsen’s Ghost, produced by Primary Stages, is set in the writer’s Oslo home in 1906, shortly after the playwright’s death. A moment or two after the lights go down, a rugged-looking fellow in black pea coat and naval cap sneaks in, burglar-like, seeking something. Later, we’ll learn that he’s an Irish-accented sailor named Wolf (Thomas Gibson, TV’s “Dharma and Greg”), the illegitimate son of Ibsen, searching for a memento of his father. But first we must meet the glamorous Suzannah, garbed in fashionable mourning clothes, and her tiny servant, Gerda (Jen Cody, clownishly limber).

Gerda—herself involved with Ibsen and Suzannah’s son, Sigurd—moves like a walking pretzel because of a spinal disability (some may find this in bad taste) that also affects her “pubis.” It seems that Gerda’s involuntary, pleasurable, crotch-grabbing sensations may somehow be related to a connection between “sciatica and habitual masturbation,” as someone puts it. Raunchy references, of course, are expected in Busch’s work, and Ibsen’s Ghost doesn’t disappoint, quickly establishing not only Gerda’s urges but those of Suzannah, who longingly recalls her late spouse as “a conjugal partner of inexhaustible pyrotechnics,” a description, we’ll discover, of questionable veracity.

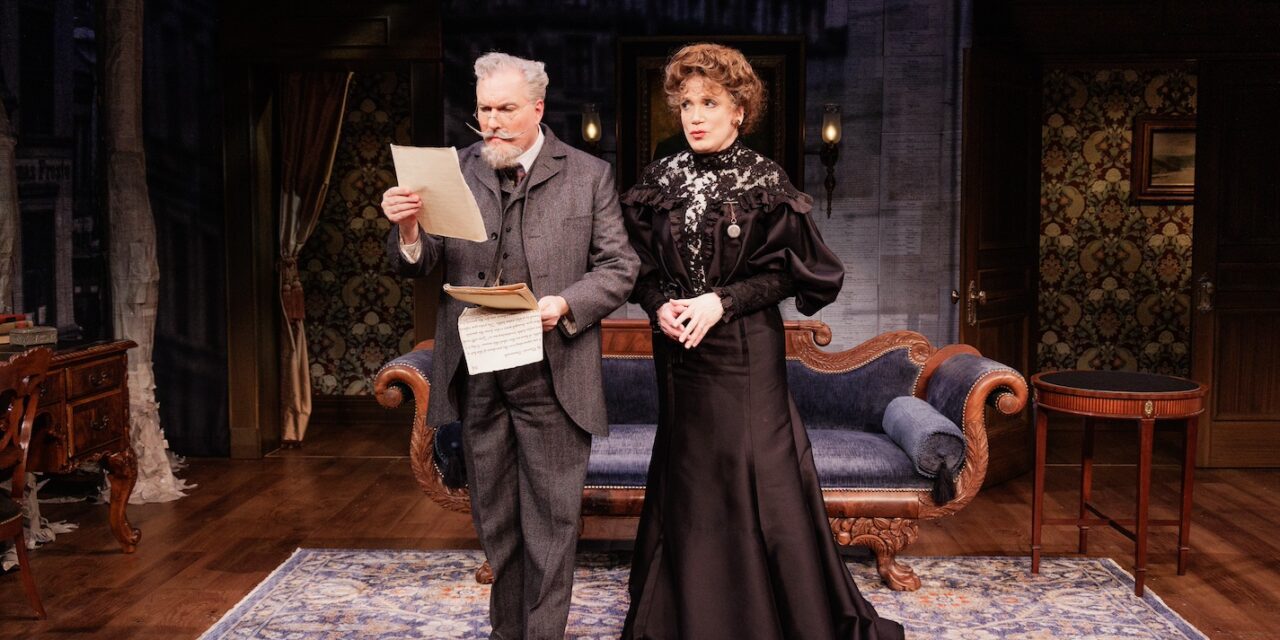

Before long Ibsen’s publisher, George Elsted, played with elegant panache by Christopher Borg (The Confession of Lily Dare), mustachioed like Salvador Dali, arrives. Suzannah, herself a writer—she once translated a play by Freytag—who abandoned her ambitions to serve her husband’s needs, wishes to have her 50-year correspondence with Ibsen published. However, their focus on domestic matters, not the plays, disturbs the publisher. Suzannah, who’s struggling to establish her own identity and place in history, also claims to have been the model for Nora in A Doll’s House.

Then follows the entrance of Suzannah’s formidable stepmother, Magdalene Kragh Thoresen (an impressive Judy Kaye, Phantom of the Opera and so much else), a prodigiously prolific writer with whom Suzannah has bad blood. Hanna Solberg (Jennifer Van Dyck, in her 11th Busch play, practically stealing the show), another writer, soon appears. Hanna, a former protégé of the master, wants to publish a diary declaring that she was the inspiration for Nora (she calls it I, Nora), and making anti-Ibsen allegations that Suzannah, with Wolf’s assistance, is anxious to prevent from being published. But the promise of a fulfilling dramatic rivalry between Suzannah and Hanna is never fully realized. (One wonders why Busch doesn’t use the name of the writer who actually was Nora’s real-life avatar, Laura Kieler, whose story parallels much of that given in the play for Hanna.)

Instead, it gets sidetracked into other plotlines, one involving a new character, the Rat Wife (ably played in drag by Borg), who lures rats to the sea, has second sight, and possesses a surprising past; another involving the intimate entanglement of Suzannah and Wolf; and one concerning the background for Suzannah’s animosity toward Magdalene. While some of this is amusing, its need for talkative exposition bogs the play down before traction is regained.

In the hands, eyes, mouths, backs, and other body parts of Busch’s priceless ensemble, lines that are relatively innocuous in print receive multiple chuckles, although too few rock the rafters at 59E59 Theaters. Still, the mere flick of a wrist, drop of an eyelid, arch of an eyebrow, or clutch of a (female) crotch can get anything from a titter to a howl. The same goes for readings delivered in posh British accents with Swiss watch timing, each sentence milked for multihued shadings as per the Sen. Katie Britt Alabama School of Melodramatic Acting. Much of the performance is delivered straight to the audience, often with a winking awareness of shared connivance.

Deftly staged over an hour and 45 minutes (with one intermission) in theatrically broad 19th-century style by longtime Busch collaborator Carl Andress, the show often totters on a perilous anything-for-a-laugh limb; the wonder is that the limb survives and that many bits do land, if not in hilarious battalions or risible explosions. Partly responsible for the occasional longueurs is the abundance of expository reference material Busch introduces. On the other hand, Ibsen’s son, Sigurd, is cited as the prime minister of Norway although his term of office ended the year before this play begins.

Busch, known for moderately flamboyant acting that subdues excess in favor of greater truthfulness, goes for broke a bit more than usual, his facial shtick alone nearly enough to make a visit worthwhile. Highlights include a scene where someone notes Suzanna’s thin lips, her head withdrawn like a turtle, and her tiny eyes, each remark followed by a comically physical rebuttal.

Designer Shoko Kambara has created a lovely sitting room, with period furnishings, including an old-fashioned porcelain stove, surrounded by towering walls depicting photo blowups of the streets and residences outside, and framed at the top with leafy branches. Staring down from its upstage perch is a portrait of the stern-faced, mutton-chopped dramatist. The house is said to be deteriorating badly, and we’re reminded several times of the ghosts of the past haunting the characters who live here.

Ibsen’s Ghost, written in charmingly faux 19th-century language, its style a pastiche of Ibsenian conversations, contains applause-generating monologues; numerous between-the-lines allusions to Ibsen’s plays for the academically inclined that will whiz by the uninformed; exceptional costumes by Gregory Gale (wait for Hanna’s archery outfit) that deserve preservation; perfect wigs and makeup by Bobbie Zlotnik; topnotch dialect coaching by Rebecca Simon; superb lighting by veteran Ken Billington; and an excellent sound design by Jill BC Du Boff. One can only hope all this helps to keep the grim-faced Ibsen’s ghost smiling, if not necessarily laughing.

Ibsen’s Ghost: An Irresponsible Biographical Fantasy. Through April 14 at 59E59 Theaters/Theater A (59 East 59th Street, between Madison and Park Avenues). www.59e59.org

Photos: James Leynse