Casual notes on show-biz books, memoirs and studies, dust gatherers, and hot off the presses.

Book Review by Samuel L. Leiter . . . .

Barry Singer. Ever After: Forty Years of Musical Theatre and Beyond 1977-2020 (New York: Applause, 2020). 389pp.

Peter Filichia. Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks: A Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2013). 288pp.

7th Edition

Books about Broadway musicals keep rolling off the presses, a sign of the subject’s enduring popularity years after the so-called “Golden Age of Broadway Musicals” has passed. Two of a relatively recent vintage are surveyed in today’s column. The first, Barry Singer’s Ever After, published in 2020, and the second, Peter Filichia’s Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks, a little more than a decade ago, in 2013.

To be exact, Singer’s survey of new shows produced between 1977 and 2020, is an updated version of his similarly titled book of 2004, originally subtitled The Last Years of Musical Theatre and Beyond. That work forms the first half of the recent book, Act One (1977-2003), with Act Two covering shows from 2004 through 2020. A year-by-year account, its first half includes not only Broadway musicals but the principal Off-Broadway examples of the period, while, with one or two exceptions, the latter half ignores Off-Broadway without an explanation.

Also, Act One is written in the third person, while Act Two is in the first, making it much more personal. In fact, Singer occasionally includes commentary from his young daughters on their reactions to shows to which he took them; don’t worry, though, his girls are smart and their comments fun to read. He seems less constrained in these chapters, even making several ruthless swipes at Donald Trump’s expense. Revivals, it must be mentioned, are almost completely ignored.

Act One has not been updated, so revivals of the few shows from that period that failed originally but were successful when revived aren’t mentioned. The book stops at the pandemic, but, for some reason makes no mention of The Girl from the North Country, which began Off-Broadway and was the last new Broadway musical to open before it, along with the rest of Broadway, shut down.

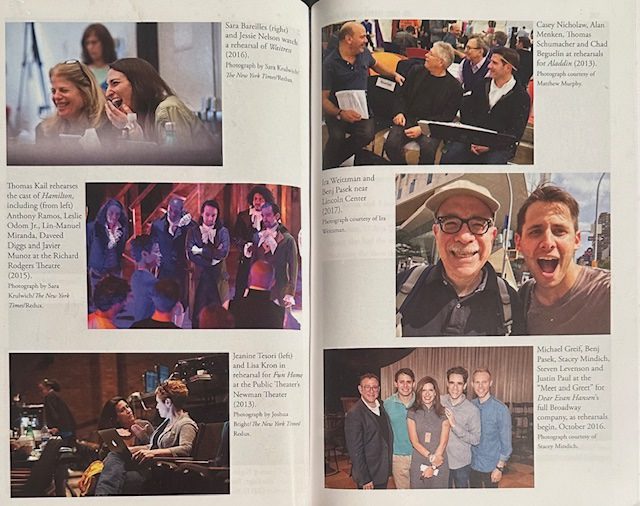

There are many minor items with which one could quibble, but, overall, this is a sprightly journalistic account of every new Broadway show for the 40-year period, most discussed in a paragraph or two; but many are given considerable space to look not only at the material per se, but at its development. In fact, a good portion of Ever After covers the way modern musicals are born, raised, and sent out into the world, including presentations out-of-town, in workshops, readings, and so forth. Supporters of new musicals unknown to the general public, like Ira Weitzman, play an invaluable role in these discussions.

Obviously, the process of production gets considerable attention as well. There’s too much to describe here briefly, but, among the well-illustrated book’s achievements are Singer’s knowledgeable accounts of which musicals helped break through the conventions restricting the form; he considers Jonathan Larson’s Rent the single most important influence on the movement.

Much attention is paid to the younger generation of musical creators, like Jason Robert Brown, Michael John LaChiusa, Adam Guettel, Jeanine Tesori, Benj Pask and Justin Paul, etc. Singer is sharply critical of many writers and shows that were huge successes (Andrew Lloyd Webber is a major target), and you may not agree with some of his assessments, but, for all its occasional flaws (like Singer’s writing about Rocky without mentioning its boxing ring staging), the book—which has an index but no bibliography—should interest musical theater aficionados.

Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks, by renowned Broadway maven Peter Filichia (a professional acquaintance) is, as its colorful subtitle confesses, indeed “opinionated.” Filichia’s ambitious aim is to explain why all those many Broadway shows that were nominated for a Best Musical Tony didn’t win—a goal of particular interest when it comes to such classic losers as Gypsy, Follies, and West Side Story, as alluded to in his vivid main title.

As per his goal, Filichia offers many detailed discussions on what he deems the weaknesses in those shows that failed to take home a trophy. Since the winners aren’t his concern, he only rarely allows that those shows could as easily be dissected for their libretto and score problems. Writing in a breezy style prone to humorous wordplay, his 12 chapters reject an overall chronological approach in favor of chapter themes: shows that already had closed by Tony Awards night; those that had longer runs than the winners; those whose producers may have undermined their success; those doomed by the years in which they ran; and so on.

Often, a chapter’s theme is so tenuous it loses steam and one forgets what’s drawing the plays under discussion together, their appearance even seeming random. Because of this structure, apart from occasional reminders, the reader also may not recall what a particular show’s competition was. It’s easy to see how the chapters could have been organized on a year-by-year basis to make this clear; given the approach taken, however, I’ll use one of Filichia’s favorite locutions for offering advice to suggest that he “should have” included a chronological appendix of all nominees.

Filichia can be ruthless with shows or artists with whom he’s displeased (like Singer, he’s no fan of Andrew Lloyd Webber). This will please readers who appreciate such candor, but others may not be happy to see musicals or artists they admire so roughly handled. Where possible, it pays to visit YouTube to view the performances he describes and make up your own mind as to how much you agree with him. He doesn’t, however, do such surgery on every loser, but only on selected ones. Many shows get little more than passing mention.

Filichia wants to focus on shows that haven’t been widely written about, like The Lieutenant (recently revived, by the way) but nonetheless spends significant time on very well-known ones, like Follies, Gypsy, and Chicago. Plot summaries, usually given in past-tense narratives, are sometimes provided, but many shows, little known or hits (like Barnum), get none at all. Frequently, important information, like the Off-Broadway origins of The Me Nobody Knows or Ballroom’s source in a TV show, is overlooked.

Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks serves as a good companion volume to Singer’s Ever After, with its many opinions contrary to Filichia’s. As anyone who’s followed New York theater awards over the past decades knows, there have been seasons so lacking in new musicals (not the present one, thankfully) that it sometimes looked like any that were mounted would be nominated, just to have some competition; such circumstances, of course, were likely to cast a shadow on the entire enterprise. It’s not, of course, an issue on Filichia’s agenda. On the other hand, if one surveys the available lists of Best Musical winners and nominees, one will find, despite Filichia’s comprehensiveness, that a few losers are either merely noted and not discussed at all (like Oh, Captain!) or completely overlooked (like Walking Happy and Grind).

Regardless of these “opinionated” cavils, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks is a fun, informative read, offering many valuable opinions and insights into Broadway musicals that didn’t win the Tony. And for readers doing their own research, it has both an index and (unlike Singer) a bibliography.

Next up: Stephen Cole, Mary and Ethel . . . and Mikey Who?

Leiter Looks at Books welcomes inquiries from publishers and authors interested in having their theater/show business-related books reviewed.