Casual notes on show-biz books, memoirs and studies, dust gatherers, and hot off the presses.

Book Review by Samuel L. Leiter . . . .

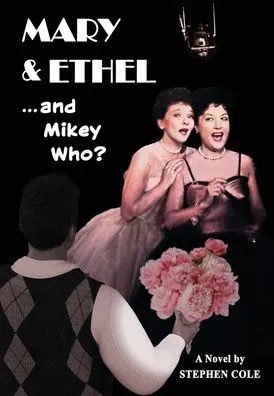

Stephen Cole. MARY & ETHEL . . . and Mikey Who? (New York: Moreclacke Publishing, 2024). 208pp.

8th Edition

Books, movies, TV series, and stage shows about time travel never seem to wear out their welcome, whether it be Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Groundhog Day, Outlander, or Back to the Future, among the hundreds (well, not so many on stage) that could be cited. How many, though, deal with someone going back in time to mingle with the greats of modern musical theater history? That unique premise is the engine driving a new book by prolific author-librettist-lyricist Stephen Cole, who has worked with many famous Broadway musical theater stars. One of them, in fact, Anita Gillette, narrates the audio version of Cole’s mildly appealing new book, MARY & ETHEL . . . and Mikey Who?

The last names of Mary and Ethel, of course, are Martin and Merman, two of the greatest musical comedy stars of the 20th century, born five years apart, in 1913 and 1908, respectively, and known for creating some of the most iconic female musical roles of all time. To name only two each from their long, prolific careers, Martin originated Nellie Forbush in South Pacific (1949) and Maria von Trapp in The Sound of Music (1959), while Merman was the first Annie Oakley in Annie Get Your Gun (1947) and Mama Rose in Gypsy (1959).

Naturally, there’s a healthy number of fabulous female musical stars today, but none are paired in the public’s mind as competing rivals the way Martin and Merman were. Jessie Mueller and Kelli O’Hara? Sutton Foster and Stephanie J. Block? Or even, given their co-starring roles in Wicked, Kristen Chenoweth and Idina Menzel? I don’t think so. Anyway, that famous M&M rivalry is at the heart of Cole’s entertaining, if far-fetched, novel, about a chubby, 25-year-old, Jewish theater geek named Michael (“Mikey”) Marvin Minkus, living in his parents’ Canarsie, Brooklyn, basement. One day, Mikey wanders through a portal in Ethel Merman’s Imperial Theatre dressing room in 1983 and ends up in the 1939 dressing room of another star, Sophie Tucker, and quickly takes a role in the following four decades of both Merman and Martin’s careers until the former’s death.

Cole (one wonders if that’s a real name or one taken in homage to Cole Porter), who writes from the experience of having personally known Merman and Martin, takes his research into the stars’ lives and loves, fabricating a fantasy fueled by historical events as experienced by Mikey, a guy very loosely based on the author himself. (See Ron Fassler’s thoughtful Theater Pizzazz interview with Cole.) The mingling of fact and fiction is nicely exercised in Cole’s portrayal of Mikey’s stereotypically kvetchy mother, Rifka, and his dad, Morris, who died of cancer before Mikey could be bar mitzvahed. One of the major themes, in fact, is the out-of-place Mikey’s coming to terms with his parents, especially the father he barely knew.

Ensconced in the past, Mikey is aided by another Mary, an African-American woman whom Cole calls Mary2, and who works for both stars but appears in multiple other capacities as Mikey’s mysterious guide through the years. Cole never manages to explain her presence, so, like much else, she must be accepted as a given in Mikey’s adventures, during which he finds himself enmeshed in the professional and personal lives of his idols. Again, for no reason shared with the reader, his encounters occur only at key moments in the stars’ lives, in Hollywood and New York. Everyone else ages but Mikey remains forever 25—which barely piques anyone’s curiosity—as the story jumps, in turn, from 1939 to 1942, 1947, 1953, 1970, and 1983.

Cole does whatever he can to justify all the usual questions of logic and plausibility that always plague such time-traveling stories. He never offers an explanation, however, about how the phenomenon occurred (no knocks on the head, dreams, magic rituals, or the like), requiring that you simply go along for the ride, even when Mikey returns to Canarsie in 1970 and co-exists with his 12-year-old persona, even befriending his own father, who never sees in him his grown-up son. In other words, if you’re going to enjoy the book, be prepared to leave your disbelief at home.

Anyone who’s read the several memoirs and bios of Merman and Martin will recognize much of Cole’s material, which he supplements with imagined but, for his purposes, sufficiently convincing letters and conversations. Merman’s brassy personality, with its salty verbiage, is contrasted with the more demure qualities of Martin, whose nastiest expression is “Oh, plop!” Their marital partners also come in for treatment, especially Martin’s bisexual, substance-abusing, controlling spouse, Richard Halliday. Gayness, in fact, is one of Cole’s concerns, the virginal Mikey’s own burgeoning sexuality figuring heavily when he’s introduced to same-sex intimacy by leading choreographer Jerome Robbins. Yes, you read that right.

Of central importance is Mikey’s involvement—in the guise of the actresses’ press agent—in fostering a rivalry between Merman and Martin as a boost to public interest in their activities. He makes it clear that the women are, indeed, good friends, but that the rivalry eventually has its downside, as described when the 1960 Tony Awards include both as nominees in the same category.

During the ceremony, it might be noted, Mikey meets a beautiful actress named Jane, who’s up for a featured actress award; only later does he realize she’s Jane Fonda. Considering that he’s such a theater freak, it stretches credibility that he wouldn’t have recognized her immediately, especially since 1960 was only 23 years before Mikey began his odyssey into the past. Similar glitches pop up here and there, most disturbingly when Cole claims that Merman was set to fly to Hollywood in March 1983 to sing “There’s No Business Like Show Business” at the Oscars in honor of Irving Berlin, “who died that year at 101 years old” (p. 61). Berlin, however, was a mere 95 in 1983 and had another six years to live. While, in a book like this, we can bend the rules a bit for the Jane Fonda bit—which many readers will catch the minute the name Jane is mentioned—the Berlin reference is just a good old-fashioned mistake.

Also, when you allow yourself to let rational thoughts infiltrate your brain while reading MARY & ETHEL, you begin to wonder why, being a musical theater aficionado, the kind who listens to show albums until their grooves wear out, Mikey—who seems to have no philosophical qualms about disturbing history—doesn’t make a fortune by trading on his knowledge of the future. Such questions must be the bane of all time travel writers.

Jerry Robbins is only one of the many famous theatrical personalities whose names are dropped; so many, in fact, that Cole provides a glossary of nearly 90 for those who don’t recognize them at first sight. Only a few, though, like Robbins, whose involvement in the HUAC hearings seeking show business communists, figure prominently in the narrative; most are window dressing chosen to give color to the theatrical world of those mid-century decades.

Many leading show business figures have offered positive blurbs for this allegedly inside look at one of Broadway’s most legendary friendships. While I can’t be as effusive as these commentators, I can’t deny having enjoyed the book, hard to swallow as much of it is. Reading what are intended to be inside secrets, told as if we’re flies on the wall, is always intriguing when it relates to familiar celebrities; however, much as Cole writes in a breezy enough style, and readers who’ve lived in Canarsie will feel a slight frisson of recognition at his references, there’s little here most musical theater history fans don’t already know.

Next up: Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography

Leiter Looks at Books welcomes inquiries from publishers and authors interested in having their theater/show business-related books reviewed.