Casual notes on show-biz books, memoirs and studies, dust gatherers and hot off the presses.

Book Review by Samuel L. Leiter . . . .

Michael Meyer, Not Prince Hamlet: Literary and Theatrical Memoirs (London: Secker and Warburg, 1989). 292pp.

Last year, after having sent my most recent book off to its publisher, I turned to a heavy reading regimen to see if I could make a dent in the backlog of books in my home library, catching up on books I never had the time to read and keeping up with new ones. After plowing through 34 mostly older books I decided to keep a casual record of my thoughts on what I was reading. Most of it was show business related (from theater history to celebrity memoir), with a rare novel or non-fictional, non-show-biz subject thrown in. I posted my comments on Facebook from late August to the end of the year. Then, at the beginning of 2024, I began posting them on my blog, Theatre’s Leiter Side, under the title “Notes on Recent Reading.” Now, with the kind support of Theater Pizzazz editor Sandi Durell and assistant editor JK Clarke, they’ll be appearing on TP, where I’ve been reviewing plays since 2012.

I’ll begin with re-postings of some of the original Facebook notes, and gradually include new material as I get to it. The first item, then, is Michael Meyer’s Not Prince Hamlet: Literary and Theatrical Memoirs, published in 1989. My comments are very brief, but later postings will be more substantial.

Meyer (1921-2000), you may know, was a British writer of Jewish background chiefly known as a master translator of Ibsen and Strindberg, and the author of massive biographies of those Scandinavian playwrights. I wouldn’t be surprised if Charles Busch consulted Meyer’s work while writing his new play, Ibsen’s Ghost. Meyer was a friend and colleague of many of the greatest British writers of the 20th century, and his book is filled with their names. Given his background as the scion of a well-to-do family with deep roots in England, and his education at Oxford, you might expect a tome of stuffy reminiscences; instead, his volume—which is decently illustrated and has an index—is filled with fascinating stories, some frankly personal.

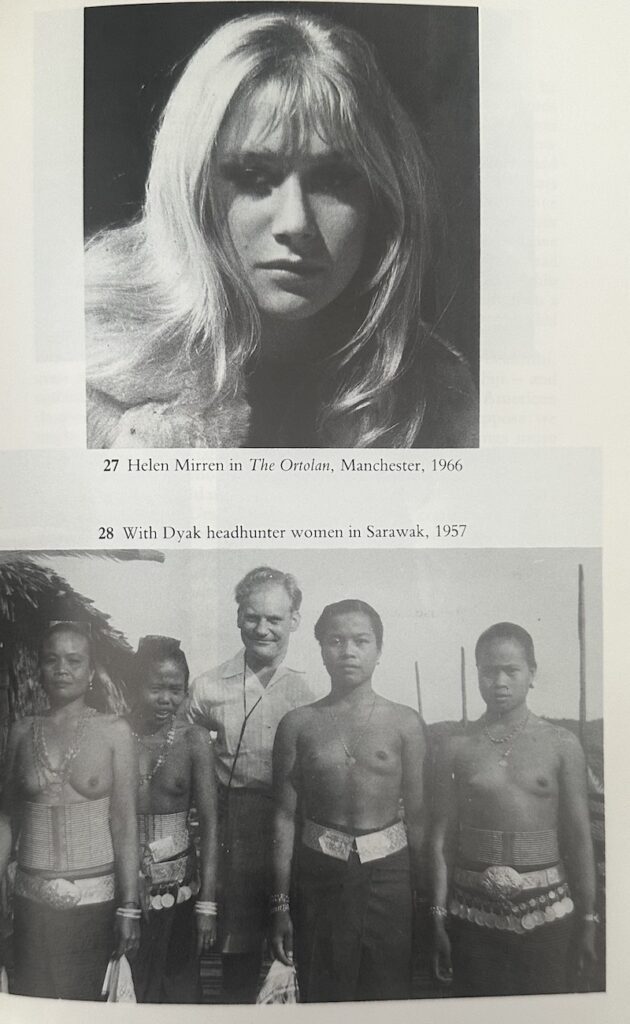

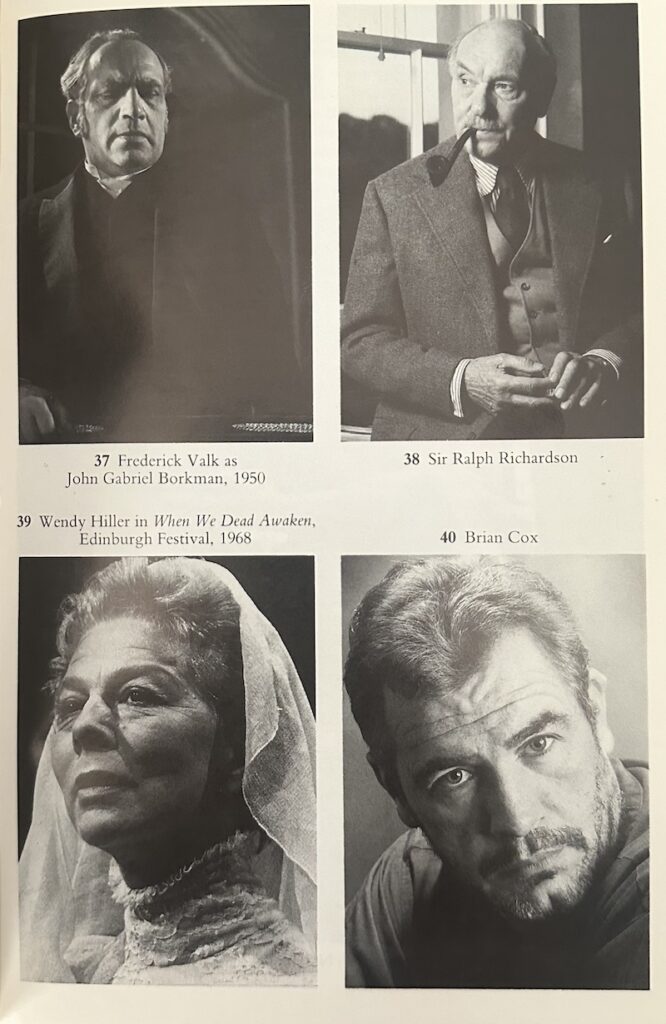

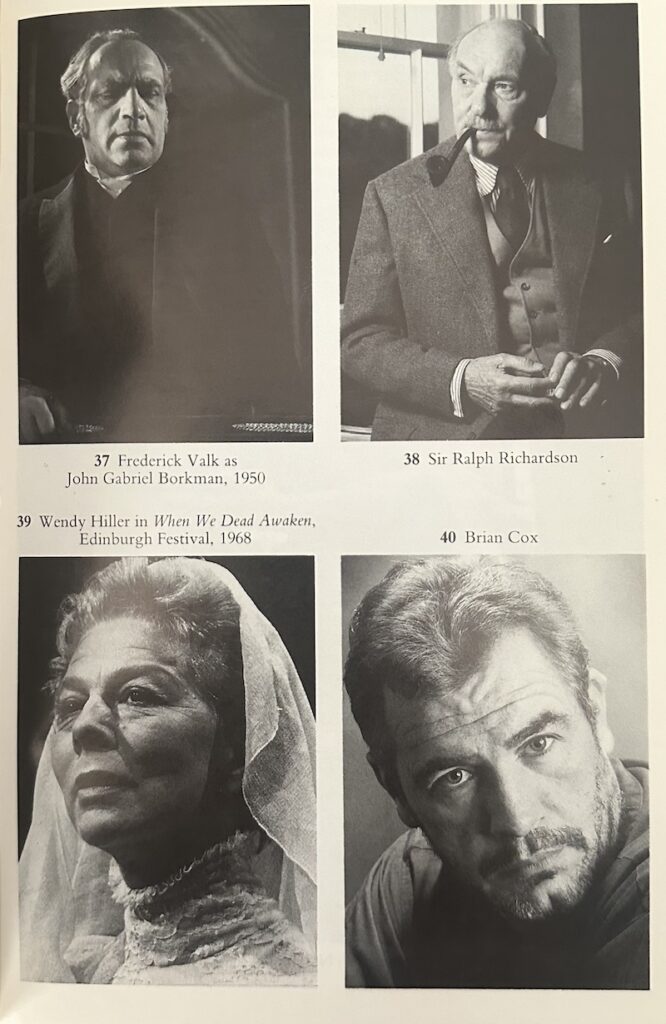

Many of Meyer’s anecdotes of famous people are both deeply insightful or laugh-out-loud hilarious, among them those involving such close friends and artists as—to cite only a few—Graham Greene, Max Beerbohm, Ingmar Bergman, Ralph Richardson, Laurence Olivier, Vanessa Redgrave, Helen Mirren, Peter Brook, Brian Cox, Helena Weigel, Patrick McGoohan, Trevor Howard, Maggie Smith, George Orwell, and the actor he considered the greatest he’d ever seen, Frederick Valk.

There are also excellent discussions of the task of translating plays, with noteworthy reference to Ibsen and Strindberg. Meyer’s years of residence in Sweden provide rarely reported-on accounts of the top Swedish actors and directors of his time. However, Meyer, like so many others in the British theatrical community, was also a cricket enthusiast, so when he now and then discussed that noble British game, I found myself in a fog. If you like cricket, though, count its presence a plus.

Next up: Lawrence Senelick, The Age and Stage of George L. Fox 1825-1877; John Gross, Shylock: A Legend and its Legacy