Better Times Program

By Samuel L. Leiter

I count twelve shows we can classify as musical revues for the New York season of 1922-1923, the season having begun in June and run through the end of May. In chronological order, they are Ziegfeld Follies of 1922, Strut Miss Lizzie, Spice of 1922, Plantation Revue, George White’s Scandals of 1922, Better Times, A Fantastic Fricassee, Greenwich Village Follies, The Passing Show of 1922, The Music Box Revue of 1922-1923, The 49ers, and Jack and Jill.

If you’re a theater buff, you surely know those titles with the words Ziegfeld, George White, Greenwich Village, Passing Show, and Music Box in them. Each was part of a regular series, featuring top musical and comedy stars of the period. They varied in the relative splendor of their sets and costumes, or how much they relied on the eye candy of pulchritudinous showgirls, but they were generally extravagant productions that could be counted on for the best in contemporary variety entertainment, usually without a definitive theme tying their ingredients together.

For this week’s installment of Leiter Looks Back, we’ll skip such well-known, star-studded series and recap the contents of five of the lesser-known revues of the 1922-1923 season, regardless of their box office success or failure. Most used formats similar to their better-known rivals, and sometimes a future star was present, their light still hidden under a bushel. Those on today’s bill, then, in chronological order, are Strut Miss Lizzie, Better Times, A Fantastic Fricassee, The 49ers, and Jack and Jill.

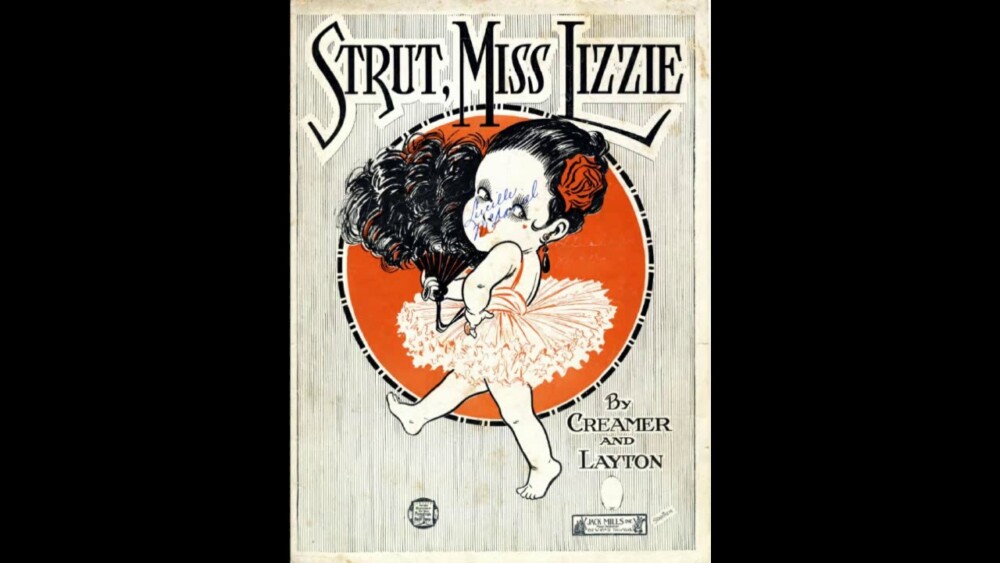

Black-oriented musical shows were a significant part of 1920s Broadway, especially after the success of Shuffle Along. Strut Miss Lizzie (Times Square Theatre, 6/19/22, 96) was a good example of the trend, having decided to move uptown after strutting its stuff at the National Winter Garden all the way down on Houston Street. It may, though, have been better off in that more intimate venue than in the larger Times Square Theatre, where the Times called it “a generally entertaining if somewhat repetitious succession of songs, dances and comedy scenes.”

Strut Miss Lizzie Program

Comedy, in fact, was hard to find, although there was no dearth of enthusiastic song and dance present. “There is always plenty of fun and rag-time and spirit in these darky shows,” proclaimed Arthur Hornblow in the insensitive lingo of the day.

Strut Miss Lizzie, whose title came from a contemporary hit song, introduced in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1921, was essentially a string of vaudeville turns. The song, played as background music HBO’s “Boardwalk Empire,” can be heard here. Billed as the show that “Glorifies the Creole Beauty”—a steal from Ziegfeld’s slogan—its numbers included Henry Creamer and Turner Layton, responsible for the music and lyrics, doing a telephone bit that squeezed in samples of their hits, including “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans.” A log cabin was the locale for “Dear Old Southland,” in which George Harvey told his Mammy he was taking her with him to New York. “This is a colored year on Broadway,” he declared. Other bits included a travesty of Il Trovatore.

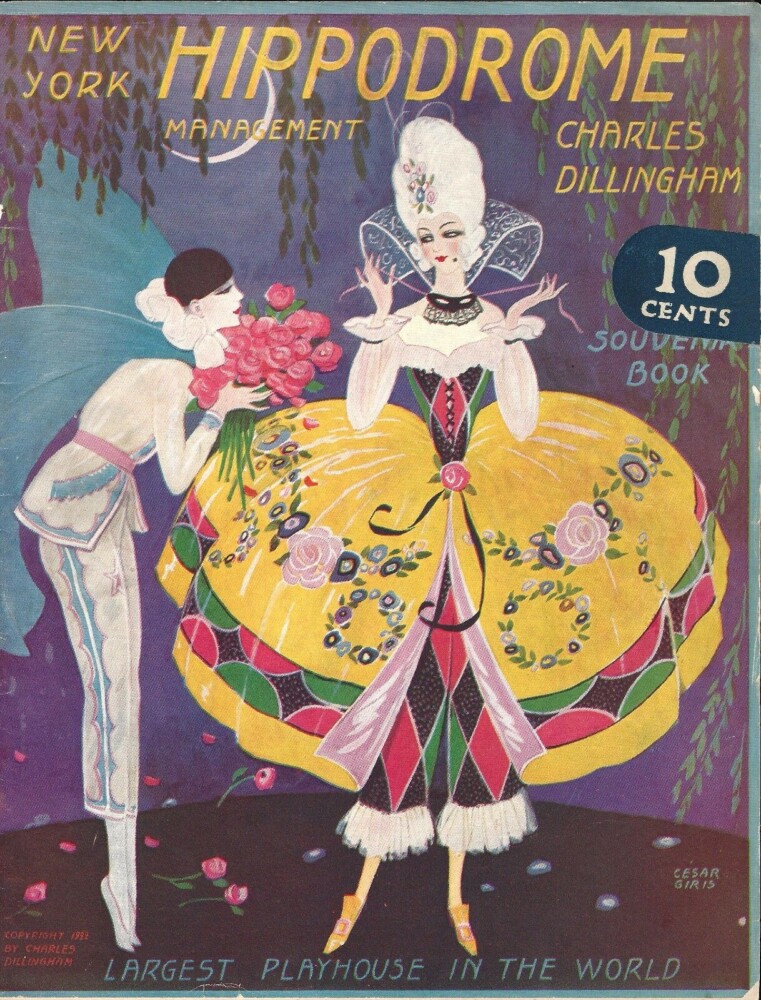

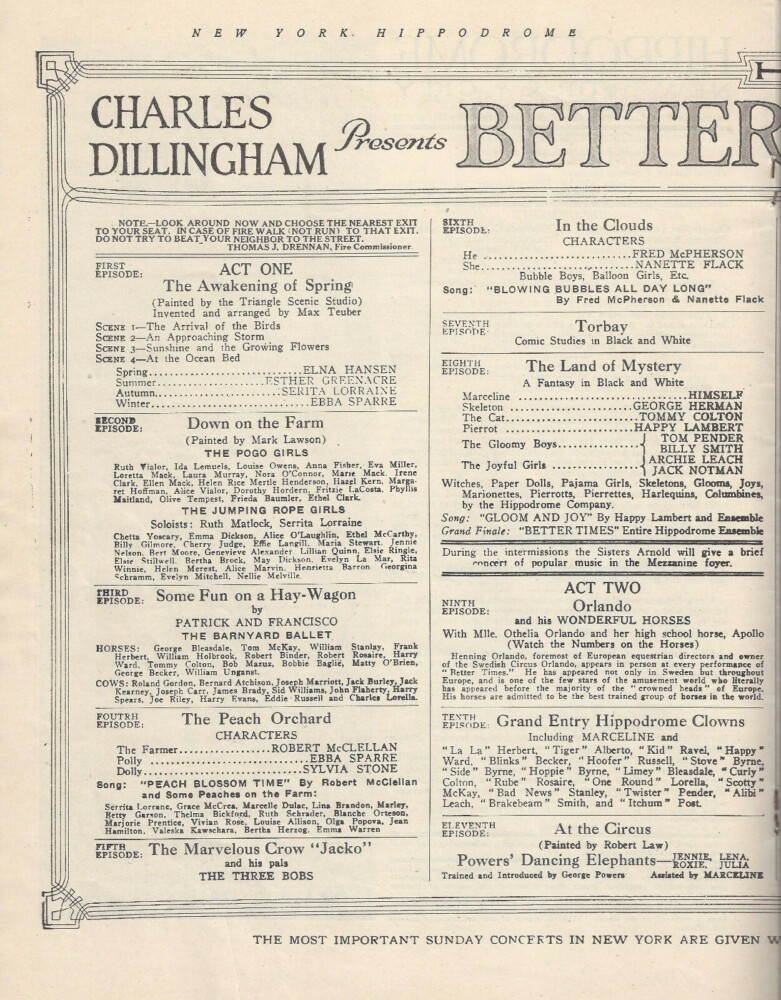

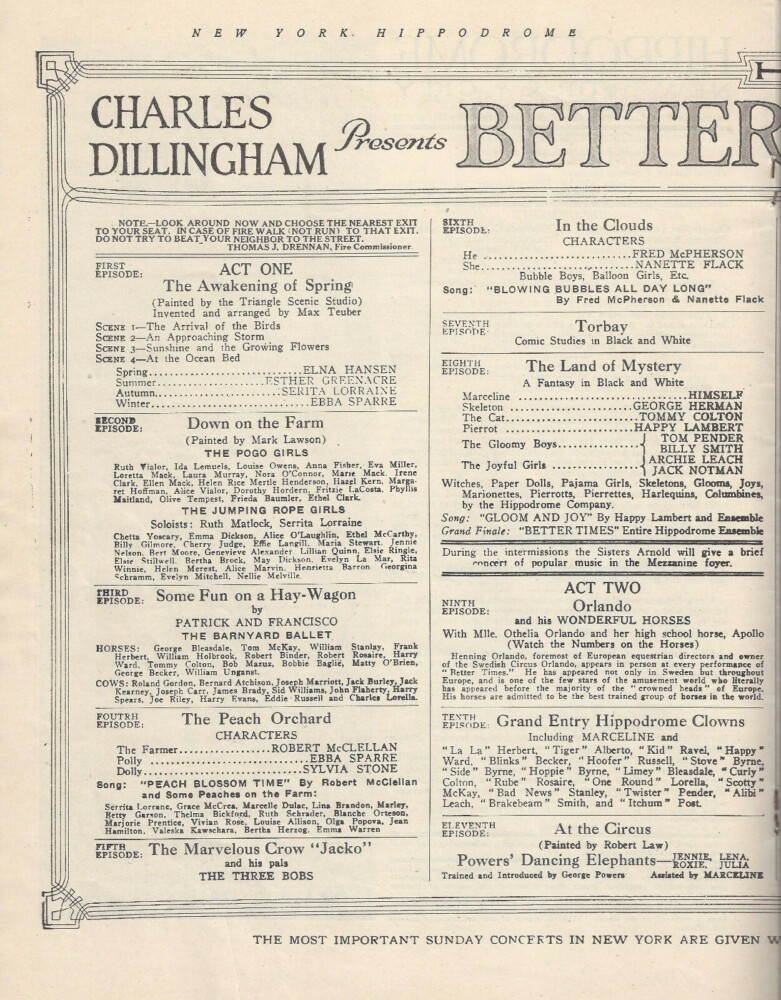

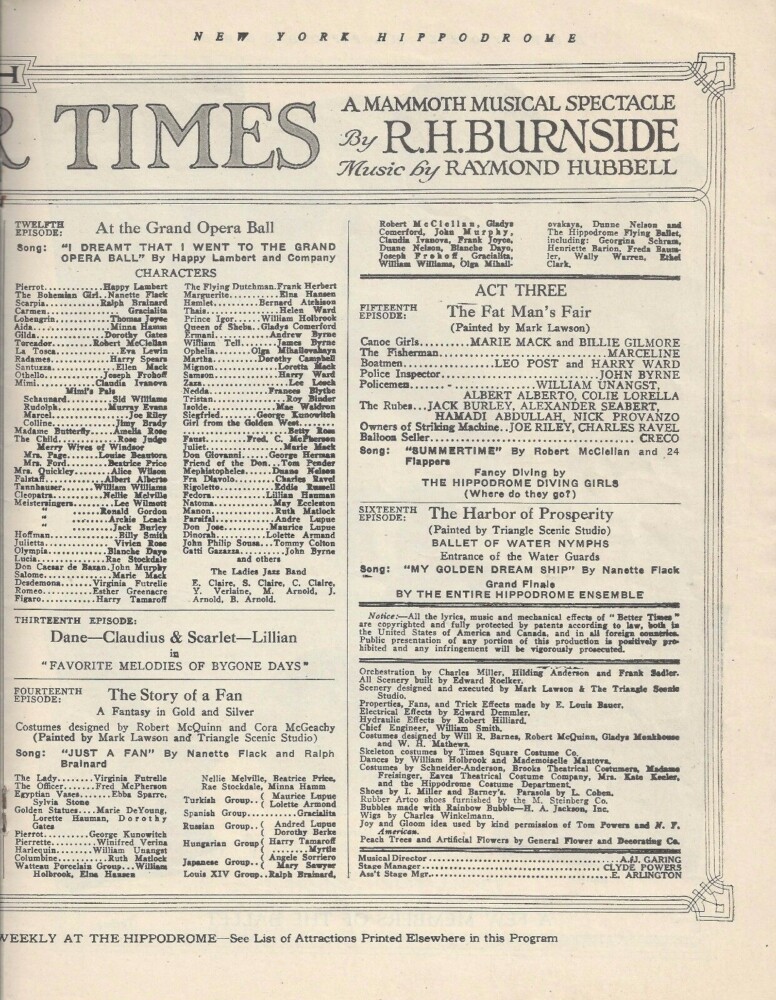

Much more attention was paid to Better Times (Hippodrome, 9/2/22, 405), a giant spectacle of a show, the biggest yet at the mammoth Hippodrome. It was the eighteenth and last of the great Hippodrome extravaganzas. The “show is by way being an elephantine Follies,” reported Arthur Hornblow. It ran for a full season with its mixture of revue and circus, ballet and pachyderms.

Better Times Program

There were extravaganza numbers, like “Land of Mystery,” an unusual special-effects presentation with dancing skeletons; “Story of a Fan,” a lavish routine with dancers dressed in giant fans rising on traps to occupy the entire stage as a gigantic overhead fan glowed in electric lights; “Grand Opera Ball,” in which the company emerged from an immense Victrola dressed as famous opera characters; and a sensational waterborne finale, “The Harbor of Prosperity,” showing Amazons in gold costumes disappearing into the waves and returning on a “ship of dreams.” (The Hippodrome had a huge tank for aquatic spectacles.)

Better Times Program

There were animal acts, such as Powers’s Elephants, Orlando’s Horses, and that inimitable avian star Jocko, “the $50,000 crow,” who batted barely a feather as he snatched balls and tiny Indian clubs out of the air. Forming a part of one of the acts was a young English acrobat, Archie Leach, who later changed his name to Cary Grant.

Better Times Program

There was little that was fantastic in A Fantastic Fricassee (Greenwich Village Theatre, 9/11/22, 111), although it did run over one hundred times in its Off-Broadway venue. Like so many of its competitors, it was a patchwork of various kinds of performance: sketches, ballets, a ukulele-playing singer, satirical bits, and a marionette show. Overall, the effect was uneven and “incredibly dull,” according to Laurence Stallings. Percy Hammond seconded the motion, calling the show “[A]s dull as an obituary.”

An interesting item was Ben Hecht and Maxwell Bodenheim’s one-act, “The Master Poisoner,” written in blank verse and done in Grand Guignol style. It was mocked, however, as was Arthur Caesar’s satire, “When the Dead Get Gay,” set in a New York mausoleum and involving two cadavers chatting about such topical concerns as Prohibition. Unsung among the singers was future star Jeannette MacDonald.

Jeannette MacDonald in the 1920s

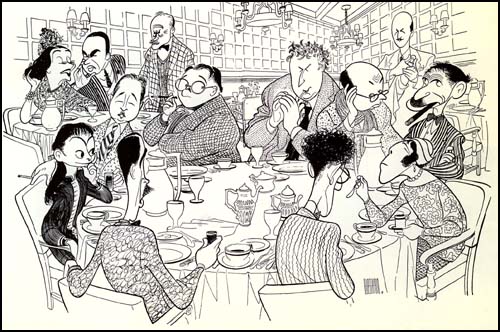

Judging by its contributors, one might have expected a show like The 49ers (Punch and Judy Theatre, 11/7/22, 15) to have run up more than fifteen performances. After all, this rare example of a revue devoted to comedy, not a combination of music and comedy, was conceived by two men who would become icons of Broadway wit, George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly. They already had scored with Dulcy and would later collaborate on the classic comedy, Beggar on Horseback. Supplementing them was a team of over a dozen notable writers, including Morrie Ryskind and Howard Dietz, Franklin Pierce Adams and Arthur Samuels, Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker, Heywood Broun, Montague Glass, Ring Lardner, and others. Another Broadway master, Howard Lindsay, handled the direction, and veteran George C. Tyler produced.

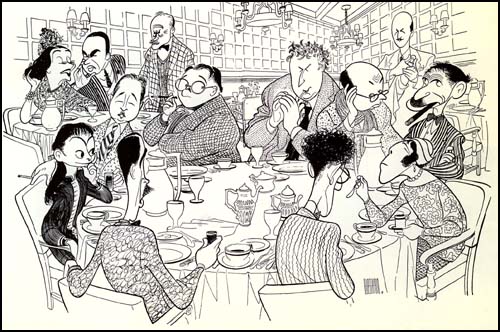

The 49ers – Al Hirschfeld drawing of the Algonquin Round Table. Clockwise, from the bottom left: Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Marc Connelly, Franklin Pierce Adams, Edna Ferber and Georsge S. Kaufman. In the background, left to right, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt, Frank Crowninshield and Frank Case.

The show was inspired by a one-night amateur revue written by the above-mentioned members of the literary clique known as the Round Table at the Algonquin Hotel, called No, Siree!. Some of them took part on stage as well but the show never rounded up the laughs its famous names seemed to promise. Its title came from its intimate, 300-seat theatre, located on Forty-ninth Street. Regardless of its title, it could not provide the required gold-nugget satire.

A principal weakness was the presence of vaudevillian May Irwin as mistress of ceremonies. Connelly stated in his memoirs, Voices Offstage, that he took over on the second night and had far better results.

On the program were bits such as Kaufman’s “Life in the Back Pages,” which depicted American life as lived in the magazine ads; “Power of Light,” Ryskind and Dietz’s Russian burlesque; Adams and Samuel’s parody of musical comedies with business themes; Benchley and Parker’s historical pastiche, “Nero”; Broun’s “A Robe for the King”; Glass’s takeoff on the funeral business; a now-famous nonsense skit by Lardner, “The Tridget of Greva”; and a Connelly-created Midwestern folk dance, “The Dance of the Small Town Mayors.”

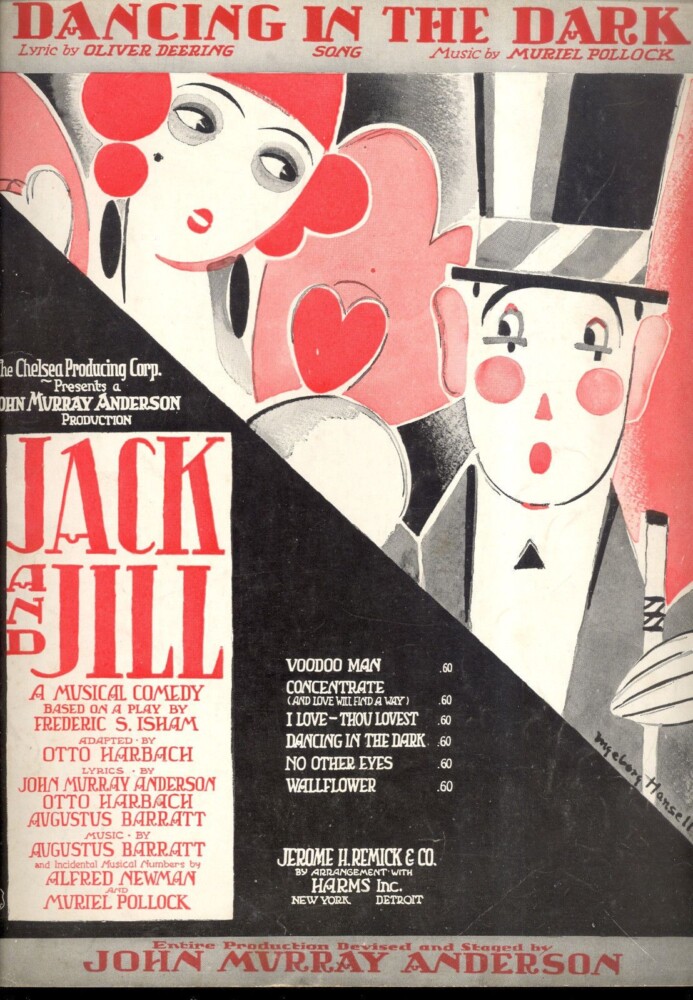

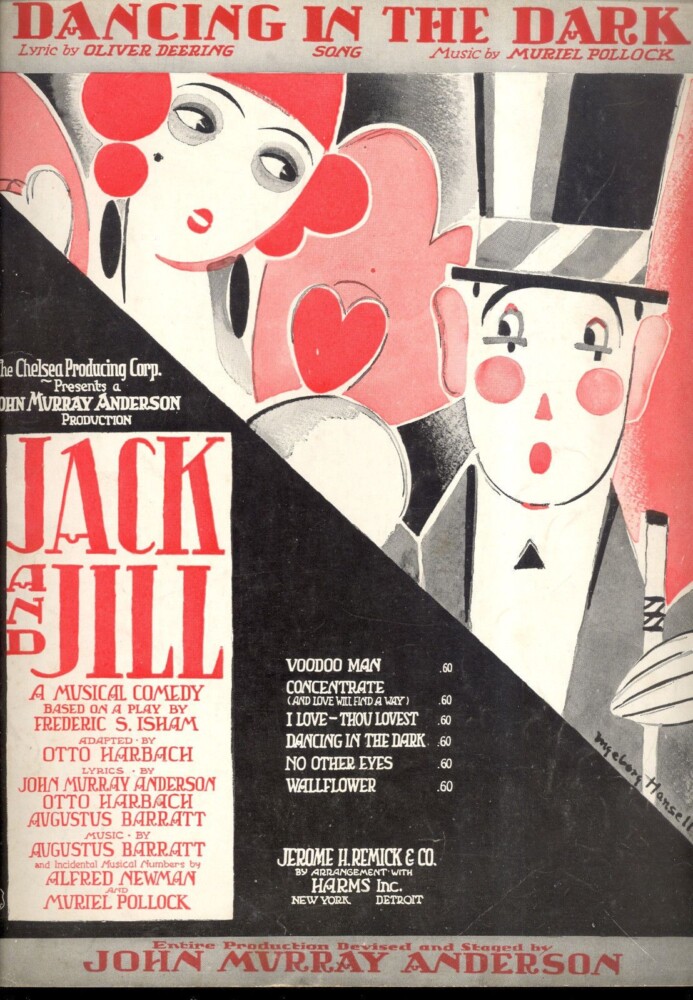

Sheet Music for “Dancing in the Dark” from Jack and Jill

Finally, we fall down the hill with Jack and Jill (Globe Theatre, 3/22/23, 92), with its “heavy and spiritless” dialogue, as Heywood Broun reported. The Post decried its “wishy washy songs” and painful attempts” at humor. Jack and Jill was actually borderline musical comedy because it possessed a storyline, albeit one that Broun called “utterly threadbare.” Augustus Barratt and Alfred Newman composed the music, with lyrics by John Murray Anderson (who directed), Otto Harbach, and Barratt.

Anne Pennington

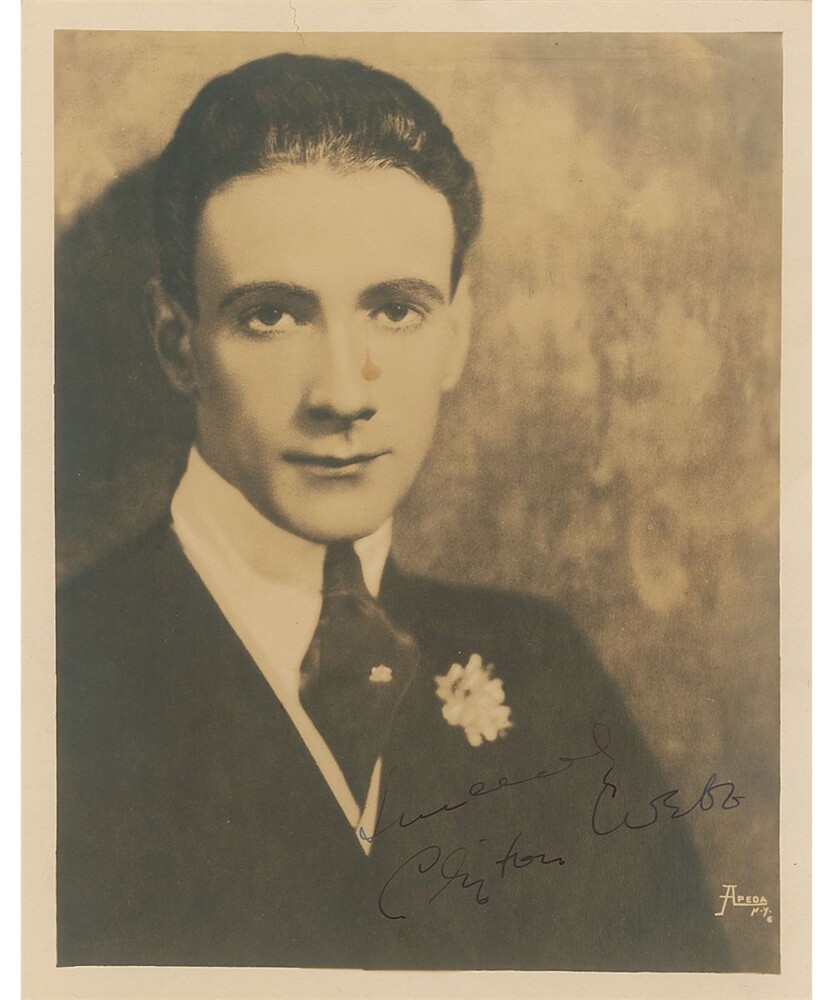

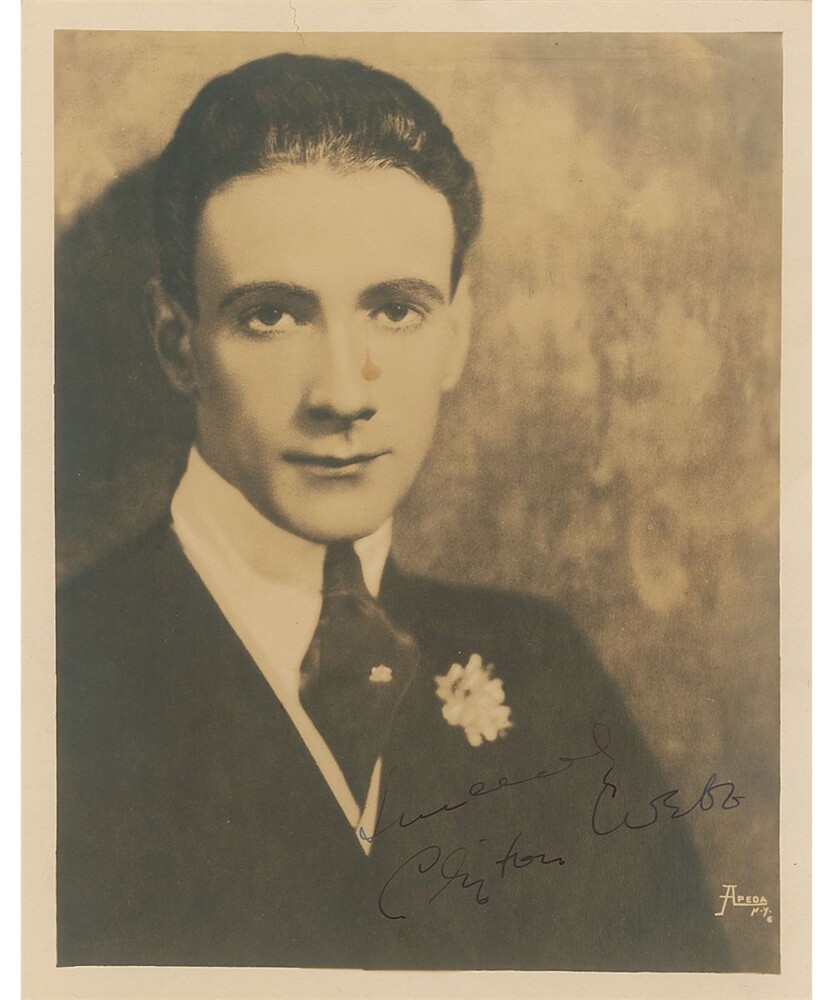

Only the delicious delights of Ann Pennington’s dances, seconded by the charms of Clifton Webb’s nimble feet saved the show from ruin. One of the songs, introduced by Clifton Webb and Beth Beri, was called “Dancing in the Dark.” Written by Oliver Deering and Muriel Pollock, it wasn’t the famous one of that title later written by Arthur Schwartz and Howard Dietz.

Clifton Webb

The book, by Frederic Isham and Otto Harbach, was about the nouveau riche Mrs. Malone (Georgia O’Ramey), an antique lover who buys an old chair said to have been made of the cherry tree chopped down by George Washington. Whenever someone sits on it, they begin to spout their truthful feelings about others. This premise was used to resolve a love story about a girl (Virginia O’Brien) who wants a certain fellow (Donald MacDonald) while her mother prefers someone else (Clifton Webb).

When we return in a week or so, it will be with a pack of revivals, one of which will be the famous Hamlet of John Barrymore. Whatever else accompanies it, that’s one Leiter Looks Back has no intention of omitting.