By Samuel L. Leiter

In the seventh volume of his Best Plays series, a disappointed Burns Mantle summed up what he viewed as the disappointing 1925-1926 season, saying that it “falls with rather a definite thud into the just average group. Its highlights, if any, were scattered and dim, it indicated no particular trend toward new artistic standards nor fell far back from such standards as previously have been achieved.”

He admits to the usual difficulty in selecting ten plays he considered representative, his choices being six of American authorship, three English, and one Russian. Among those he respected but chose to overlook was Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock, which, after seeing those he picked, was clearly a big mistake. Almost as bad an oversight was his completely ignoring Noel Coward’s Hay Fever, which continues to be revived.

On the other hand, it’s not likely anyone today would groan over his leaving out those he seriously considered before abandoning them: Maxwell Anderson’s Outside Looking In, Sidney Howard’s Lucky Sam McCarver, Philip Barry’s In a Garden, Eugene O’Neill’s The Fountain, Marcel Pagnol and Paul Nivaux’s Merchants of Glory, or Daniel Rubin’s Devils. Few, in fact, would even know anything at all about these plays.

Several of Mantle’s ten best are likely to strike a similar chord of non-recognition, even if they know the playwrights’ names. Consider, for example, Channing Pollock’s The Enemy, William Hurlbut’s Bride of the Lamb, Marc Connelly’s The Wisdom Tooth, Frederick Lonsdale’s The Last of Mrs. Cheney, or John Van Druten’s Young Woodley. My assumption (just a guess, of course) is that people interested enough in New York theater history to be reading these words would—even if they’ve never seen or read them—at least have heard of most of the following: George Kelly’s Craig’s Wife, O’Neill’s The Great God Brown, Michael Arlen’s The Green Hat (because of its place in Katherine Cornell’s career), George S. Kaufman’s The Butter and Egg Man, and Sholem Ansky’s The Dybukk.

Regardless of how close (or far) I am in my suppositions, I’ve chosen four “best plays”—five would have made this far too long—to introduce what I consider the least familiar of the ten, slightly edited from how they appear in my Encyclopedia of the New York Stage, 1920-1930.

Channing Pollock, author of The Enemy (Times Square Theatre, 10/20/25, 202), had been considered a hack playwright until he began writing serious, thoughtful plays in the 1920s. These were generally platitudinous, melodramatic works with ethically or spiritually relevant themes. Such was this jeremiad against the cruelty and folly of militarism, inspired by the quote, “Oh wad some power the giftie gie us to see oursels as others see us.” Mantle’s review summed up the theme: “That hate is the real enemy of humanity; that wars are inspired by hate; that there is no real difference between peoples and that if hatred and greed are banished from the earth there will be no more war.”

Pollock’s preachment, directed by Robert Milton, was set in a Vienna flat as seen in June 1914, shortly before the outbreak of the war; scenes set in August 1914, March 1917, and June 1919 follow, showing the effects of the holocaust on the “enemy” side so as to point up how, apart from hatred itself, there are no “enemies” in war.

The critics viewed a shrewdly affecting play in The Enemy, one that demonstrated the author’s talent of manipulating his audience’s feelings by resorting to the most obvious tricks of his trade. The main objection raised was that it was more of a propaganda philippic than a work of dramatic art. Richard Dana Skinner was especially vociferous in his indictment, referring to the play’s “muddled thinking” and its “well-meant fallacies.”

In his autobiography, Harvest of My Years, Pollock reported that a principal role was filled by Fay Bainter only at the very last moment and that the opening was going to be postponed had the actress not been signed up. Bainter accepted the part at two in the morning and, to Pollock’s amazement, at the ten the same morning had learned all the many lines for her first act.

The other best-known cast member was Walter Abel, unless you’re enough of a buff to remember the names of Olive May, Charles Dalton, Jane Seymour (no, not that one), Russ Whytal, and so on.

William Hurlbut’s Off-Broadway play, Bride of the Lamb (Greenwich Village Theatre, 3/30/26, 103), also directed by Robert Milton, is a melodramatic study of the effects on a small-town Western family of their confrontation with a handsome, passionate, sincere evangelist. It depicts the Bowman family, the “drunken sot” of a father, Roy (Edmund Elton); his neurotic, repressed wife Ina (Alice Brady); their daughter, Verna (Arline Blackburn); and what happens when the good Rev. Albaugh (Crane Wilbur) sets up his revival tent next to their home and takes residence with them for a week.

By the end of his stay, Mrs. Bowman having thrown herself at the charismatic religionist, has poisoned her spouse with shoe cleaning fluid; Verna has taken to repeatedly confessing her sins; and Albaugh’s wife, not seen for eighteen years, returns. This causes Mrs. Bowman to go bonkers. She dresses like a bride, and, as per Atkinson, “Like Ophelia, beflowered and bedecked, singing bits of emotional hymns . . . trips off to the madhouse.”

Hurlbut’s demonstration of the link between sexual desire and religious frenzy was heavily laced with Freudian platitudes, displeasing some critics. Others were disturbed by the faulty construction, especially the introduction, which Brooks Atkinson called “meretricious,” of the preacher’s wife near the end.

Although these feelings were widely shared, a critical contingent was nonetheless shaken by the play’s dramatic force. Joseph Wood Krutch found “a sturdy competence about the handling of the plot and about the characterization of the principal personages which sustains the interest and keeps alive a vigorous concern for the fate of the people involved.” Leading designer Cleon Throckmorton did the realistic, knickknack-filled set. Of the cast, the biggest name was that of Alice Brady, but her overheated performance did her little credit.

Marc Connelly, a frequent collaborator with other playwrights (notably, George S. Kaufman), is best known for his once beloved retelling of the Bible through the lens of a Black Southern congregation, The Green Pastures. That work is now essentially discarded because of the evolution of racial attitudes. Far less well known is his fantasy-comedy The Wisdom Tooth (Little Theatre, February 15, 1926, 160), his first non-collaboration, a respected, if flawed, play about a man with an inferiority complex. The Walter Mitty-like character was brought to life by Thomas Mitchell (Scarlett O’Hara’s father in Gone with the Wind).

Bemis (Mitchell) is a timid clerk, a cowering “yes man,” holding no opinions of his own. Told by the girl he loves (Mary Phillips) that he is a mere shell of a man after he has been unable to stand up to his boss when a secretary was fired, he drifts into a dream of his youth wherein he is seen as a spunky fellow (played by a child actor) who believes in fairies (!) and is unafraid of bullies. His self-esteem returns, he confronts his boss, and he wins the girl.

Bordering on sentimentality, but never dipping into bathos, the play had a James M. Barrie-like whimsicality. At its best it was a play of “homely fantasy, comedy of sentiment, amusing and obvious accuracies of small observation,” commented Stark Young. John Mason Brown, however, was perturbed to find that Connelly had “sharpened neither his humor nor his pathos sufficiently to endow the result with fantasy.”

In 1926 The Wisdom Tooth’s 160 performances were enough to qualify it as a hit, which brings us to a tale told by the show’s producer John Golden in his memoir, Stage Struck John Golden. Golden admits that he never even read the play, depending entirely on the recommendation of his highly regarded director Winchell Smith. Knowing only the plot outline, Golden went to Florida and left the show entirely in Smith’s hands. He soon heard that the play was in dire straits during its tryout period. Willing to risk a failure, though, he had the play moved to Broadway. Soon, still in Miami, he began to receive congratulations on his new hit. Asked by financier Otto Kahn how he managed to come by such success, Golden replied, “One way is to get out of the way and let Winchell Smith and Marc Connelly do their darndest.”

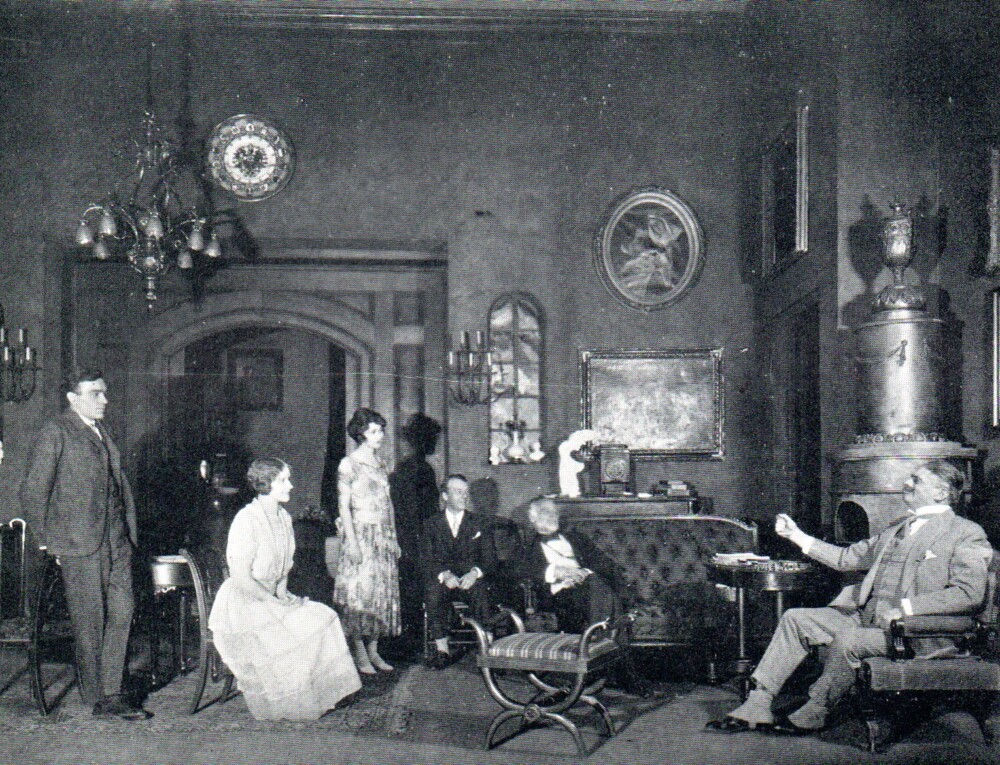

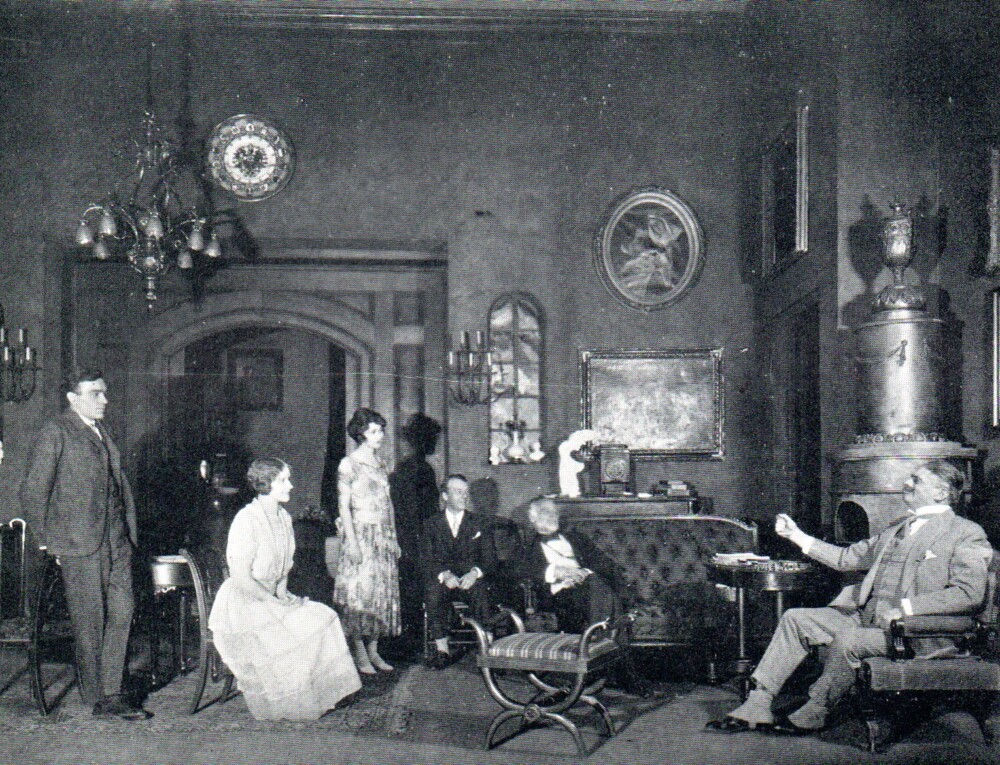

Winchell Smith also was the helmsman behind our fourth and final selection, Frederick Lonsdale’s British drawing-room comedy, The Last of Mrs. Cheyney (Fulton Theatre, 11/9/25, 283), which George Jean Nathan dismissed oddly as “a crook hickpicker.” The Times said it “calls itself a comedy but . . . is really a pleasant melodrama sugared with typical paradigms of the newer English school of epigrammatical writing.” Ina Claire, Roland Young, and A.E. Matthews, the latter two British and all three stage luminaries of the day, were heaped with accolades for the lighthearted esprit with which they displayed their skills. At the time, the play was still running in London, with Gladys Cooper in the title role.

The play’s stereotypical premise allowed Claire to portray Mrs. Cheyney, who turns up in London society after a supposed widowhood spent in Australia. While a guest at a country home, she is sought after by two eligible bachelors, one the stuffy old Lord Elton (Felix Aylmer), the other a younger man, the roguish Lord Arthur Dilling (Young). Mrs. Cheyney turns out to be a jewel thief in cahoots with Charles (Matthews), the cynical butler, with her eye on a certain string of pearls. When Lord Arthur discovers her profession, he offers her a choice of evils: the police or a romp in bed. Her choice of the former gains his respect, and the plot climaxes with their romantic union.

The critics cited Lonsdale’s wit and charm as reasons for his appeal, despite the silly plot. Arthur Hornblow maintained that it was “one of the thinnest and the same time most beguiling comedies in several seasons.” Of the actors, said the Times,

Miss Claire was radiantly lovely and in supreme command of the impishness and slyness and cuteness that were in her role. Mr. Young . . . was smooth in his phrasings and most engaging as a character who was not without his bounderisms. Mr. Matthews, a glorified and glamorous butler and the head of the crime syndicate . . . made quite plausible the author’s assumptions that all the women of the play should adore him.”

The next installment of “Leiter Looks Back” returns to the 1924-1925 season, moving on to four or five of its musical contributions. The candidates—to cite a handful—include The Vagabond King, Sunny, Tip-Toes, Sweetheart Time, The Girl Friend, Dearest Enemy, The Cocoanuts, and No, No, Nanette. I’m looking forward to looking back.