By Samuel L. Leiter

This series began in the spring of 2020, when the pandemic made it seem as if live theater, on, off, off-off, or even off-off-off might never come back, or, if it did, might not do so in the ways to which most people were accustomed. While we waited, masks in place and, ultimately, vaccinated, for the pandemic to subside, we found other outlets than live performance for our need to see the human experience examined, interpreted, and presented in the flesh by writers, directors, actors, and designers.

Some of us who write about New York theater but were prevented from seeing it live found an outlet in the many streaming productions that sprouted like mushrooms on our TVs, laptops, tablets, and phones. I reviewed a couple of such works but found the experience dishearteningly forced. I hope no one is offended, but I quickly lost interest in watching actors, separated from their partners while communicating with them on a (mostly) laptop screen in little boxes while, looking into a camera, pretending they were in a shared space.

I admired the cleverness and grit it took to keep theater going, even if only digitally, but, unable to engross myself in it, turned instead to the documented past, reminiscing about old-time Broadway and Off-Broadway, good, indifferent, and bad. One expression of this reminiscent urge was the present series, Leiter Looks Back; another was one I did for Theater Life called “On This Day in New York Theater,” soon to expire; and, finally, my own Theatre’s Leiter Side blog, which will soon have posted over 600 essays about productions between 1970 and 1975 taken from an unpublished manuscript of mine.

But, hooray and hallelujah, live theater is coming back and it couldn’t be too soon. With that in mind, as well as the oncoming summer’s obligations and pleasures, not to mention an all-consuming book project, I regretfully announce that today’s entry of Leiter Looks Back will be its last. With the promise of live theatre just over the hill, I hope to return to Theater Pizzazz in the fall, joining my wonderful colleagues in reviewing New York plays and musicals, alive and kicking.

For this last edition, Leiter Looks Back does so at two revivals of the 1925-1926 season, whose new plays, musicals, and revues were the subject of earlier postings. As noted in my last one, there was a sizable contingent of revivals during the season, one of which was advertised as “Hamlet in Modern Dress,” being the first such production of the play. The seventh (and last) Hamlet of the decade, a period also notable because of John Barrymore’s 1922 version, starred British actor Basil Sydney, in a staging originally seen in London. It opened at the Booth Theatre on November 9, 1925 and lasted for 88 performances, a solid total for a classical revival.

Viewers seemed to find the experiment of Hamlet in 1920s circumstances worthwhile, if not triumphant. The production came hard on the heels of Walter Hampden’s version, which was still on the boards, offering ample scope for comparison. George Jean Nathan revealed all the prejudices he held against the modern dress approach (now as common as those in period dress) before seeing it. He marshaled every argument he could to ridicule the concept, but discovered in the theatre that he felt “like an ass,” for the production was “actually more interesting, more exciting, more moving and more vivid than any Hamlet of other days.”

What Nathan and others saw was a Hamlet that was not as electric as it was merely because its garments were modish and its accoutrements familiar, but because it was a superbly staged (by James Light) work of theatre art.

The new approach, it was reported, brought great lucidity to the play. Hamlet, deprived of all the fustian of historical vestments, stood forth, said Time, as “a credible, relatively simple and most amazingly shrewd commentary on human weaknesses.” In the staging, social rank and character type were so clearly delineated by costuming that the play’s humor as well as its pathos seemed far more natural than usual.

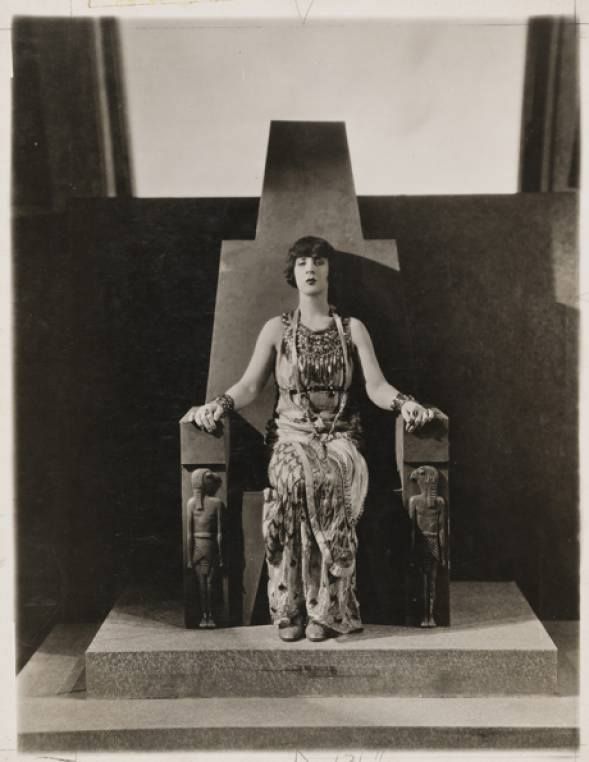

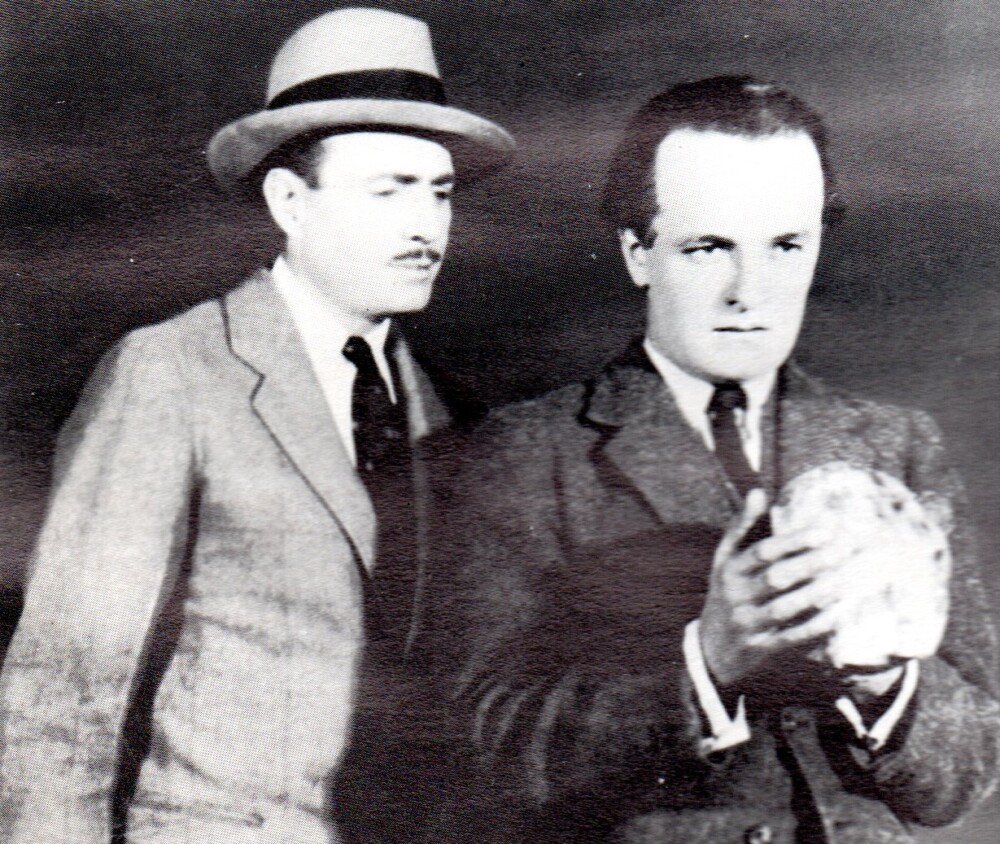

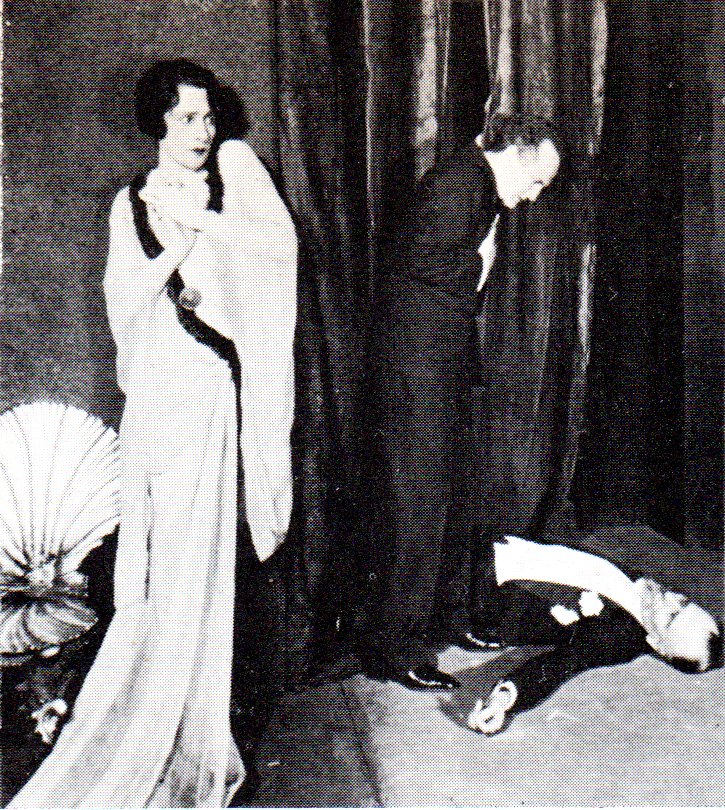

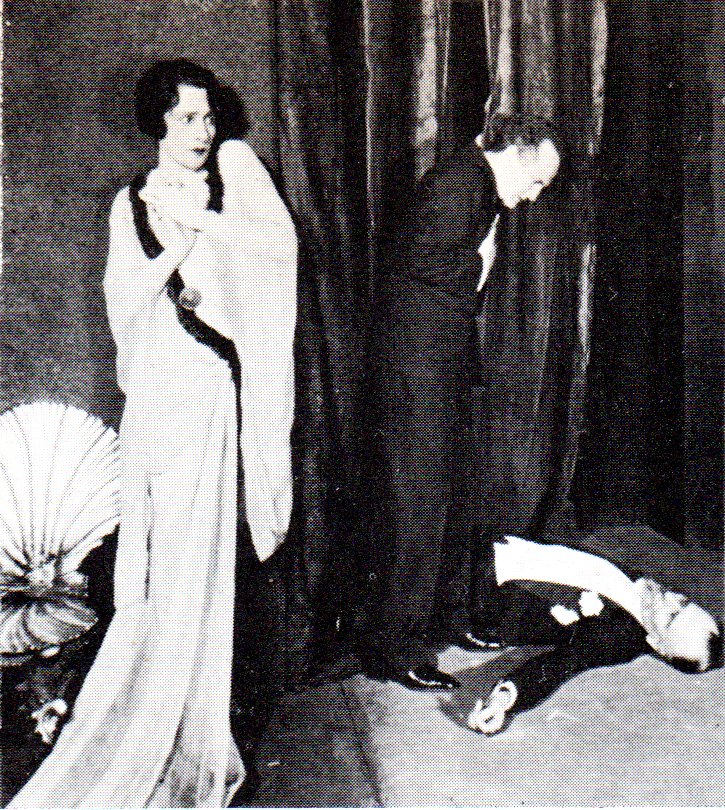

Light’s direction introduced a court at which Claudius (Charles Waldron in the role that Sydney himself would play in the famed Laurence Olivier film of 1948) wore a cutaway or flannels as the need arose; Polonius (Ernest Lawford) was a well-groomed gentleman with a monocle; Hamlet appeared at various times in a double-breasted suit, dinner jacket, silk dressing-gown, plus-fours, sporting cap, and smoking either a pipe or cigarette (especially in the soliloquies); Gertrude (Adrienne Morrison), who also had the nicotine habit, with her hair bobbed and in the latest Paris fashions; Ophelia (Helen Chandler) dressed like a Roaring Twenties’ flapper; the First Gravedigger (Walter Kingsford) in a bowler, puffing on a pipe, and working in shirtsleeves; and the soldiers donning contemporary military garb.

The telephone was much in evidence, and Polonius was killed by a bullet. The lines were spoken colloquially with little attempt at emphasizing the verse, a method that made the words carry a freight of meaning often lost to modern auditors. Strangely, though, as the Times pointed out, the dialogue was purged of the more bawdy licenses of Elizabethan speech.” Potential censorship was even then a factor with which to contend.

The stellar performance was Lawford’s Polonius. The Times said he made the man “fatuous, supercilious, plausible to the extreme,” and not at all the conventional “doddering old fool.” Sydney’s Prince was “as honestly thought out and as rationally projected a Hamlet as” Nathan ever saw. But Richard Dana Skinner thought him too continually “neurotic and emotional,” when he should have been heroic in the Hampden vein.

Despite the relative abundance of revivals, many closing early or created for deliberately brief runs, the only other to find significant acceptance was the Theatre Guild’s production of George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man. Directed by Philip Moeller and designed by Lee Simonson, it opened at the Guild Theatre on September 14, 1925, and ran for 181 performances. A large part of the reason for that comes from the presence of the hugely popular acting couple, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne in the leads, Bluntschli and Raina.

War, heroism, and the glorious traditions of soldiery were the targets skewered by this 1894 satire (first staged in 1898). Its pertinence in the post-World War I years was greater than ever, and its universality was well-appreciated. Richard Dana Skinner declared, “His theme is simply the futility and nonsense of self-deception. War, warfare, and whereabouts are all accidents.” But a few believed, with John Mason Brown, that Arms and the Man had not weathered the storms of time. “It is thin and weak and its sparkle is somewhat dulled.” Such opinions, of course, did not prevent the play from having countless revivals, worldwide, a fate it continues to enjoy.

To most, Simonson’s colorful sets were outstanding and the company’s acting of the first water. Naturally, the Lunts sucked up most of the critical oxygen. “The romantic Raina of Miss Lynn Fontanne,” beamed Skinner, “is crisp and delectable—nothing less—and fittingly matched against the precise common sense of Alfred Lunt.”

Other revivals of the 1925-1926 season, some admired, some rejected, included 1919’s The Jest, Italian playwright Sem Bennelli’s romantic drama of Renaissance intrigue, with Alphonz Ethier and Basil Sydney in the roles first played by John and Lionel Barrymore; Walter Hampden returning with Cyrano de Bergerac in his repertory season; Eva Le Gallienne in a pair of Ibsen revivals, John Gabriel Borkman and The Master Builder, productions that helped lay the groundwork for her Civic Repertory Theatre, where it cost only $1.50 to attend; two separate attempts at The School for Scandal, one for a single, invitation-only performance; a flop reprisal of An Unchastened Woman, a 1915 hit already seriously dated; an effective mounting of the 1874 French melodrama, The Two Orphans, played in the classic melodramatic style; an appreciated staging by Winthrop Ames of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe; a dud Off-Broadway version of another nineteenth-century tearjerker, East Lynne; and moderately well-approved, but short-lived resuscitations of Shaw’s Androcles and the Lion and “The Man of Destiny” (by the Theatre Guild); Shakespeare’s Henry IV (with Otis Skinner as Falstaff and Basil Sydney as Prince Hal); and Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

And thus does Leiter Looks Back say farewell after around two dozen visits to Theater Pizzazz. Thanks to Sandi Durell for providing the space and JK Clarke for his editorial assistance. Henceforth, Leiter—vaccinated and masked (if necessary)—will be looking forward to covering the upcoming season, one that, perhaps 100 years from now, and not because of a pandemic, someone else will be fondly looking back upon.

[Thank you Sam, this has been an amazing, enlightening and educational series that helped get us all through the long days and nights of quarantine and theater drought . . ed.]