Theater Review By Ron Fassler . . . .

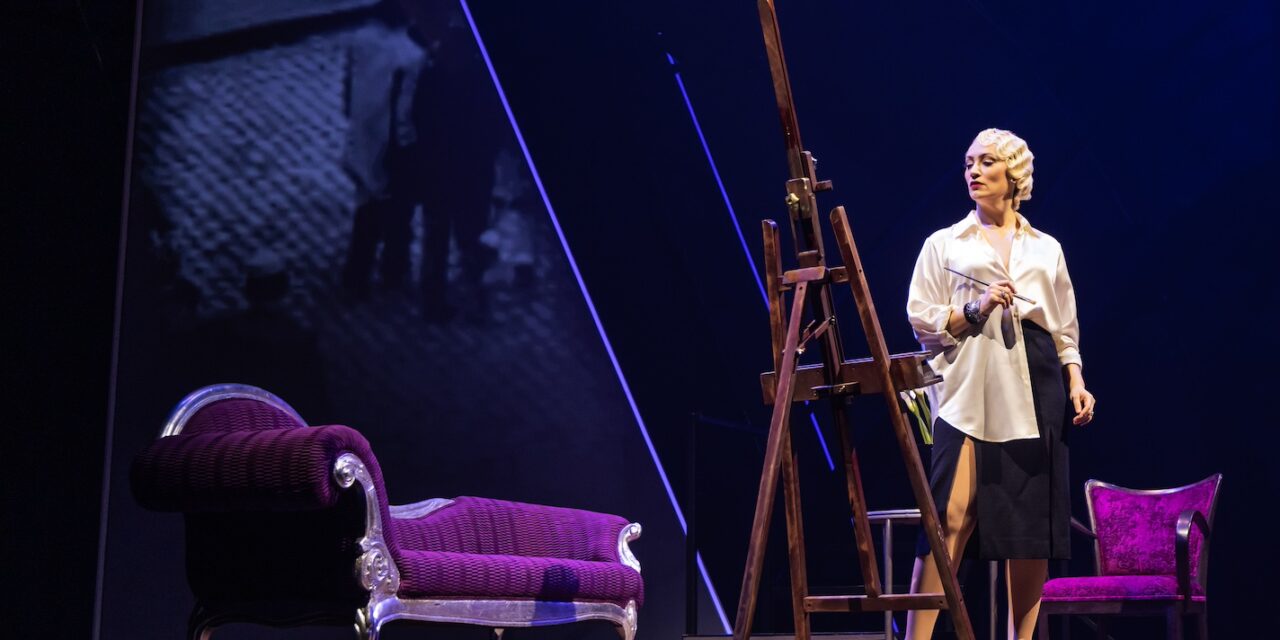

Once the new Broadway musical Lempicka begins, two things become instantly apparent: 1) a musical history lesson is in store, and 2) it is going to present a thoroughly revisionist history. You might say that Sunday in the Park with George, a musical about another artist, is also largely fictitious, but it never sets itself up as anything different. Lempicka is a biographical story that fakes a lot of its action. With a hundred years of hindsight, the show is viewed through an updated lens that distorts rather than magnifies. Much of what transpires is done more out of convenience than conviction, which ultimately fails in its landing successfully. That said, it consistently projects a visual lushness that can’t be denied and a very talented cast does its best to sell it. If you exit the Longacre Theatre deflated over a dimness in its storytelling, there’s sunniness in its physical production.

With Rachel Chavkin at the helm, a director of pictorial flair and with usually well-calibrated instincts dramaturgically, things should have gone better. In Dave Malloy’s Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 and Anaïs Mitchell’s Hadestown, she put a special imprint on both its design and construction and managed to tell their sprawling stories with clarity and cohesiveness. Perhaps stymied by Lempicka’s self-conscious book—by Carson Kreitzer and Matt Gould (based on a concept by Kreister)—things seem to have slipped past her critical eye. As it stands now, it’s a thorough mishmash of truncated time and shallow relationships, with a complex title role that can’t hold the center. Surrounded by characters who sometimes upstage her, Eden Espinoza seems in over her head at carrying the musical on her shoulders. Yes, she can wail with the best of the former Elphabas, but there’s no “there” there. Things ring hollow when they should stir the soul—for Lempicka’s story is certainly interesting enough to conceive around it.

The artist Tamara de Lempicka (1898-1980) was a Polish painter born in Warsaw and who was living the high life in St. Petersburg when the Russian Revolution broke out. Penniless, she fled to Paris, found buyers for her art, then was in danger once again when the city fell to the Nazis. Having moved to the United States, she spent the final years of her life in Mexico, long enough to see her once-forgotten paintings begin to sell for millions of dollars. She was also bisexual in life and art, with her paintings consisting mainly of voluptuous nude women reflecting her sensuous nature. Married to a former Russian aristocrat, the musical creates a lesbian lover out of two women that Lempicka was known to have had relationships with in order to form a love triangle. What should be sexy and shattering isn’t especially titillating or dramatic. Set against the intimidating backdrops of the most politically consequential events of the twentieth century, the stakes are very high. How the characters deal with them needs to have similar stakes and, though they’re stated, we don’t feel them. And that’s a problem.

Some of this might have to do with Gould’s book, which tries a bit too hard to nail down its global and sexual politics. As co-lyricists, Kreitzer and Gould’s work is fine, although the score is heavy with power ballads allowing for a sameness to creep in. Of course, this is something that only seems to get worse as time goes by in how musicals are crafted nowadays. Still, there are enough enjoyable tunes, leaving room for certain performers to soar. And there are some lovely orchestrations by Cian McCarthy.

Amber Iman does all that she can with the underwritten part of Rafaela. Her voice is glorious and she cuts a sharp figure. But she is ultimately let down by the construction of her role more as character motivation for Lempicka than as a real character. The same downfall is met by Andrew Samonsky as Lempicka’s husband; another rich voice in search of songs that might explain his wants and needs better. In support, George Abud is outstanding as a fascist on the rise, and Natalie Joy Johnson shines as a lesbian whose dreams die a quick death under fascism. A lot of the later action mirrors so much of what we’ve seen in other shows (particularly in Cabaret) that comparisons can’t be ignored.

And then there’s the incomparable Beth Leavel, who has very little to do; but what little she does makes you wish for more. Her power ballad late in the show is as close to what drums up any real feeling in the show, and she is playing a minor character. And that’s a problem.

Technically, it’s hard to improve upon Ricardo Hernández’s set, skeletal and bold at the same time. Costumes by Paloma Young are first-rate (especially for the often scantily clad chorus) and the lighting by Bradley King is Tony-worthy. The choreography by Raja Feather Kelly is invigorating and, if often not in exact period mode, excites all the same. Again, Rachel Chavkin knows how to stage things visually and keep any show interesting. With Lempicka, she fights the good fight. Only, after more than two-and-a-half hours you might feel as if you’ve gone thirteen rounds with no knockout punch scored.

Lempicka. Open run at the Longacre Theatre (220 West 48th Street, between Broadway and Eighth Avenue). www.lempickamusical.com

Photos: Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman