By Marilyn Lester . . .

Anyone who’s successfully completed a jigsaw puzzle will instantly understand what a complex and amazing undertaking polymath Mark Nadler accomplished with his one-man theatrical piece, Hart’s Desire. This play with music was conceived and performed in the full-out Nadler fashion—full throttle and high, high energy, with large portions of fun plus sagacious insight along for the ride.

Harts’ Desire is billed as “the show that Lorenz Hart and Moss Hart would have written (thus the apostrophe after the “s” in the title, which itself is a delicious pun). It’s also described as a “1940s Musical Fantasy.” And herein lies a pointer as to why this impressive work bespeaks its considerable worth: from the fertile and clever mind of its author, the text is made up entirely of the lyrics of Lorenz Hart and the words of Moss Hart. Think about that feat; it is quite remarkable. There are one or two exceptions. The music for “Smart People” is by Nadler, rather than Hart’s musical partner, Richard Rodgers, and Nadler also tweaked the music of “Good Bad Woman.” But why quibble? The slight deviation from form is artistic license at its best and most effective.

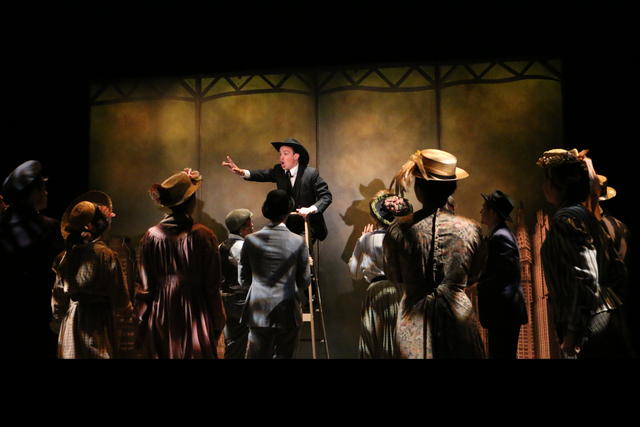

Another remarkable facet of the two-act Harts’ Desire is that there are eight characters, all played by Nadler. That’s speaking and singing in eight different voices. For this presentation at The Laurie Beechman Theatre, the conceit was that we, the audience, should consider ourselves investors interested in mounting the work on Broadway—for that, as Nadler instructed, was the way it was done back in the day. The creators of a property themselves would present their work to potential backers in a lavish apartment or hotel suite. And thus began the unfolding of Harts’ Desire.

What glues the two Harts together, at first glance, is a slight strand or two of commonality surrounding their beyond-prolific contributions to stage and screen… and also their sexuality, a driver for Nadler’s approach to the work. Lorenz was presumed gay and Moss presumed at least bisexual, but neither ever addressed their sexuality, at least in their work. For Nadler, however, an admirer of those works, a lot more common ground in personality emerged to him, and voila! Harts’ Desire was born—thus the play the two Harts would have collaborated on had they put their minds to it, with the freedom to include gay and bisexual characters.

Those eight—somewhat stock characters reminiscent of screwball comedies and certain genre films of the 1940s, not to mention Frank Loesser’s Guys and Dolls—happen to be good fun. Harts’ Desire is the kind of screwy work that also has wit and intelligence and a dollop of pathos to back it up. In a parallel universe it’s the kind of property that Charles Busch would have created with himself in the role of Althea Royce, the “raven-haired femme-fatale and theatrical leading lady of indeterminate age.” Since Nadler is all of the characters, it can take a while to figure out who’s who, but perhaps the best way to experience and enjoy Harts’ Desire is to yield to it and not work too hard at figuring out who’s who. Soon enough these theatrical types of writers, directors and performers in the play spring to individuated life with typical Nadler zest (and even and often sing duets).

Musically, Nadler has executed the miracle of taking existing music, sensibly integrating those works into the plot and assuring they do the job of moving the script forward. There’s even a leit motif, a theme that cleverly runs throughout, spoken and sung, in “I Could Write a Book.” Adding spice to the work is the inclusion of barely known Hart/Rodgers songs along with the well-known. Tunes such as “I’ll Tell the Man in the Street,” Take and Take and Take” and “Good Fellow Mine” are not ones likely to turn up in cabaret acts or concerts. On the other hand, it was a treat to hear the many, many verses of two familiar numbers, “The Lady Is a Tramp” and “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered.” Turning “My Funny Valentine” and “Glad to Be Unhappy” into poetic story songs very much added to the gravitas of the plot. And, of course, because the author and performer of Harts’ Desire is the multi-talented Mark Nadler, there was tap dancing and a second act overture in a piano medley played by Himself.

A la The Producers, the fantasy ending of Harts’ Desire is a twist—with an important message to boot. Hats off to Nadler to creating a work from the heart (pun very much intended) that’s not only happily entertaining but has been “assembled and arranged” to give pause for thought and reflection too.

Next performance: July 20 @ 7 pm Tickets: https://web.ovationtix.com/trs/pe.c/11101283

Additional Dates: August 24 and September 21

Photos: Conor Weiss