By Samuel L. Leiter

Part I

This is a true story I’ve told to a few friends over the years but never, in my recollection, revealed in print. It happened in 1961, when I was 21 and in my third year at Brooklyn College. This July, if I manage to slide by Covid-19 and am still kicking, I’ll be 80, so perhaps now, with the dearth of theatre news, and some extra time on my hands, this is the best moment to record it. It’s a tale I’ve always been proud of even though, in the scheme of things, it’s little more than biographical trivia. I hope you enjoy it.

At 21, I was an avid student of all things theatre, on stage and off, in performance and in written form. I couldn’t read enough plays, books on theatre, or theatrical critiques. I thought I wanted to be an actor, or a director, or both but I was also obsessed by theatre history (not theatre theory, be it noted).

One of my favorite courses, given over two semesters, was a survey of Shakespeare’s plays taught by a controversial English Department professor named Bernard Grebanier. (Among my classmates was Addie Bianchi, who would become Marisa Tomei’s mother, and Tom Topor, who wrote the play Nuts.) The controversy surrounding Grebanier, which I was too green to fully comprehend at the time, stemmed from his having denounced a colleague in 1941 for being a communist.

A Falstaffian figure with a remarkably resonant voice I can still hear in my head, Grebanier taught the plays by reading them and stopping to comment on particular passages, drawing on a wide range of opinions based on his personal experiences and his scholarship. He read the words so well that their meanings were crystal clear. When he read something funny, his own pleasure was represented by a snort. Again, I can still hear those snorts, nearly 60 years later.

A man of colossal ego, he never stopped puffing his chest by criticizing the major Shakespeare critics in order to advocate his own theories. You can get a brief idea of the man by reading the Wikipedia essay on him here. As that source notes, one of Grebanier’s principal achievements was a book called The Heart of Hamlet, which argued against any notion of Hamlet being or playing mad, or of being a procrastinator.

He was absolutely livid about Laurence Olivier’s film version of the play, which was sold as “The tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.” Instead, Grebanier insisted that Hamlet was a Renaissance hero, a brilliant, athletic man constantly taking action to achieve revenge, although stymied by circumstances.

Another professor of mine at the time, who had an even greater influence on me, was Wilson Lehr. Wilson, who joined Brooklyn College as head of its Speech and Theatre Department in 1958, the same year I entered as a freshman, directed me in several plays. One was Shakespeare’s Cymbeline, in which I played the supporting role of Pisanio. Grebanier came to see it and was very kind to me in his response. I realize now he was being more polite than honest.

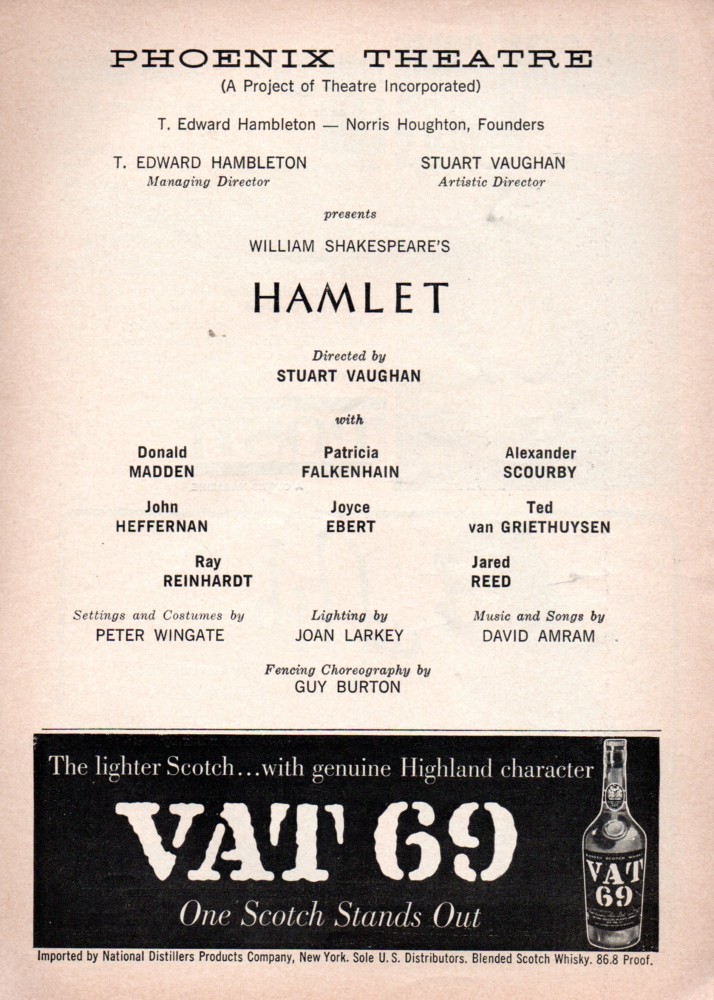

Wilson Lehr sometimes bestowed his favors on students he liked by taking them to the theatre as his plus-ones. In the spring of 1961, I accompanied him to see a then red-hot young actor named Donald Madden (note: some sources give his birth year as 1928, others as 1933), who was playing Hamlet at the Phoenix Theatre in the East Village, on Second Avenue and East 12th Street. The place once served as Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theatre. Later in the decade it served as home to the sex revue Oh! Calcutta! (which featured two of my former Brooklyn College classmates!).

The Phoenix production, staged by Stuart Vaughan, a brilliant director who would play a major role in Joe Papp’s Shakespeare in the Park, reached 102 performances. To cite previous long runs of the play at the time, this was two more than Edwin Booth’s 1864 100-performance run, the same as John E. Kellerd’s “forced” 102-performance run of 1912, 30 less than John Gielgud’s 132 in 1936, and 31 less than Maurice Evans’s 131 for his trimmed-down “G.I. version” of 1945.

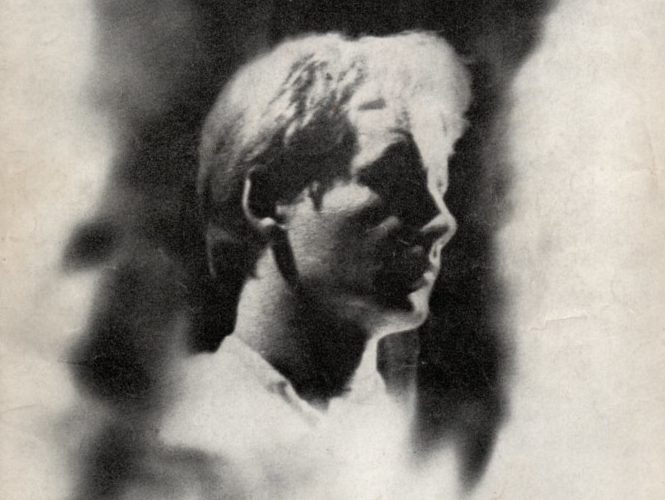

Madden was getting the kind of raves that should have made him a bigger star than he ever became before dying of lung cancer (at 49 or 54, depending on your source).

Howard Taubman, The New York Times critic, wrote, on March 17, 1961:

Mr. Madden can move; he can speak, and he brings a mind to Hamlet. A slim figure in black with a rumpled blond wig, a lean, pale face and haunted, penetrating eyes, this Hamlet is instinct with passion. But the surging emotions are under control. Mr. Madden is thus able to give the role a sense of growth and intensification.

It is astonishing how integrated a conception Mr. Madden has arrived at. His words and action have an invisible unity. He can speak one soliloquy as he scarcely suppresses an almost ungovernable impulse to writhe and pound his head on the ground, and he can turn to another like “To be or not to be” and make it a whispered, anguished meditation.

There is a brave, eager youthfulness in this Hamlet. He flings himself against a wall with abandon and gives the players their instructions with a feverish vivacity that does not conceal the thought behind the planning. But he also stands quietly and speaks the lines to the skull of poor Yorick with affecting simplicity.

I’d seen Olivier’s movie version, but Madden’s was my first live Hamlet. In later years I’d see dozens more, but none equaled the impact on me of this first one. A big part of the reason is what happened afterward.

Part II

It happened that Madden was a former student of Wilson’s at City College. He not only knew we were coming but was planning to go out with us afterward for coffee. As we sat in a Second Avenue coffee shop, I was bursting with excitement. This was not only because I was in such intimate proximity to an actor who had just gripped me with a performance as thrilling as any I’d ever seen. More to the point was that, moment by moment, Madden had seemed the complete vindication of everything that Grebanier had written about Hamlet.

After the usual pleasantries and compliments, I burst out with my question. “Mr. Madden. I’ve been studying a book called The Heart of Hamlet by Professor Grebanier at Brooklyn College. Your performance seems to have been influenced by it. Did you or Mr. Vaughn happen to read this book in preparing for your production?” The star responded by saying something like: “Yes, we certainly did. Not that we followed everything in it, but it definitely played a part in how we carried out our intentions.”

I could barely wait to get back to my Shakespeare class and tell this news to Grebanier. As I expected, he was elated, and made a big thing about it during his lecture. He then went further, and wrote to Taubman of the Times to let him in on the news.

Sure enough, within a week or two, on April 30, 1961, Taubman published an essay in the Sunday Arts section of the Times about it. He’d read The Heart of Hamlet and used his space to note the similarities to it of the Madden-Vaughn production. In a piece titled “Manly Hamlet: Phoenix Version Avoids Sick, Mad Approach” Taubman noted how perceptively this production realized Shakespeare’s intentions.

If you wish to discover how perceptively, you should not only visit the Phoenix but also read Bernard Grebanier’s The Heart of Hamlet . . .

How much, if at all, this book influenced the Phoenix production, no one can be sure. Mr. Vaughan and Mr. Madden read it, but say that they arrived by independent routes at a conception that corresponds to Mr. Grebanier’s. No matter. What counts is that the “Hamlet” evoked by Mr. Grebanier and in the Phoenix Theatre has its roots firmly in Shakespeare and his Elizabethan world and not in tortured interpretations that ignore the playwright, the design of the play and the character of the theatre and public for which he wrote.

Taubman reminds his readers of all the familiar analyses of the play, which often ignore Shakespeare in pursuit of narrow interpretations that tell more about the analyzers than the play. He continues:

Mr. Grebanier demolishes the contentions of analysts like [John Quincy] Adams, J. Dover Wilson and a host of others. . . . In his judgment Hamlet is not insane, does not procrastinate and is not flawed by an excess of sensitivity, thoughtfulness or morality.

Mr. Grebanier argues convincingly that Hamlet’s fatal flaw, like that of Oedipus, is his rashness. The climax of the drama, therefore is the killing of Polonius.

And so on. Taubman continues with a concise summary of Grebanier’s main points and goes on to note specifics in the Phoenix production that conform to them. “The result is a production brimming with theatrical sweep and color.”

By the end of the semester, I was firmly ensconced in the heart of Grebanier as one of his star pupils, although I was by no means as expert at the plays and their interpretations as others in the class. I just happened to be at the right place at the right time when Wilson Lehr took me to see Hamlet and meet afterward with its star.

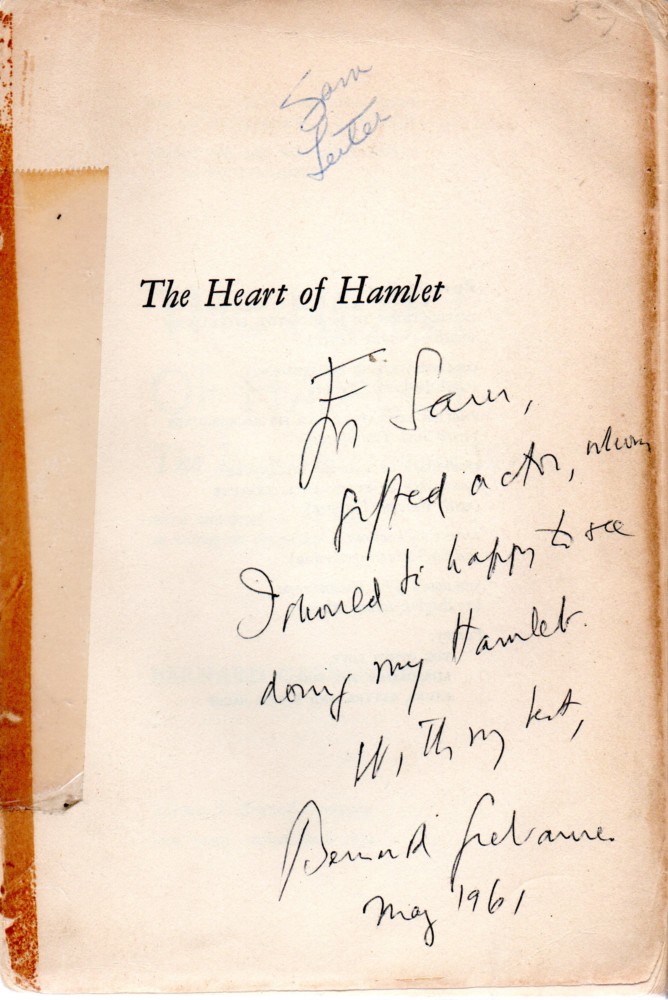

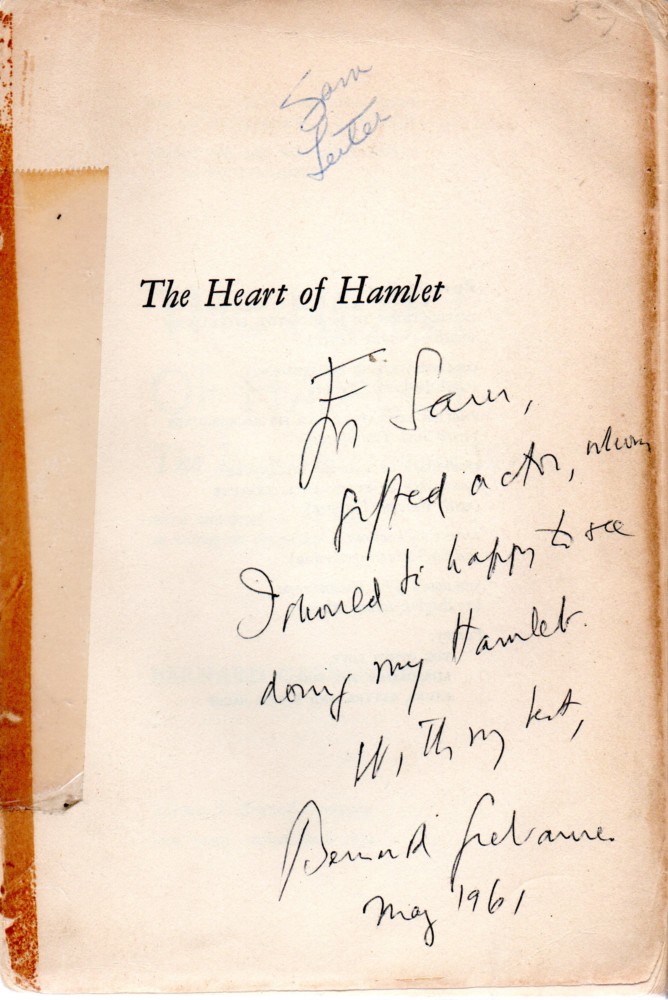

I still have the dog-eared, now coverless paperback that started this whole fuss. On it, Bernard Grebanier wrote the following: “For Sam, gifted actor, whom I should be happy to see doing my Hamlet. With my best, Bernard Grebanier, May 1961”

I never did play Hamlet (Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice was my major Shakespeare role in college), nor could I ever have done with him what Donald Madden did. But I’m still here to tell the story of what happened because of the night I met Hamlet.

My having been the conduit for this tiny moment in the history of theatrical journalism was, to that point, my proudest accomplishment, one I hope I haven’t overly embellished in the telling six decades later.

— March 2020