By Marilyn Lester . . .

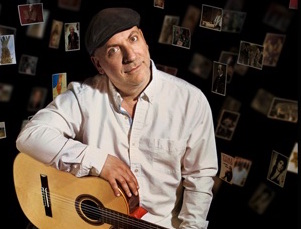

The work of Samuel Beckett, the Irish poet, playwright and writer, has long been a strong part of Bill Irwin’s stage life. It’s the perfect marriage of text and performer—the deeply intellectual author of absurdist and existential work, with the likewise deeply intellectual interpretive process and storytelling capabilities of Irwin. In On Beckett, Irwin has created a fascinating and completely engaging piece of one-man playwrighting and showmanship. It’s a piece honed to perfection by the actor’s resonant, authoritative vocal tone, combined with physical dynamism and obvious passion for the subject. What Irwin has ultimately come up with is a kind of super-fun TED talk with an honest-to-goodness dramatic arc. He begins simply, on a kind of Socratic question and answer footing, and gradually takes us lightly and precisely down the Beckett path to the big payoff of total immersion into Beckett’s world.

Irwin, who’s a Tony Award-winning actor, director and writer, has been performing On Beckett for some time now. He brought it to the Irish Repertory in 2018 and subsequently received a Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Alternative Theatrical Experience. It’s a work of maturity, developed over years of studying and playing the Beckett works. Irwin insists he’s not a Beckett scholar, but we beg to differ. He may come at the canon from an actor’s point of view, but the exploration has nonetheless bestowed upon him an expertise that can’t be denied, plus the certainty that the key to Beckett is through clowning, which is Irwin’s great love and most profound talent. In this age of identifying, Irwin most identifies as a clown—the archetypal sort whose physical style of tragi-comedy can be traced back through history and who’s always served some deeply rooted societal purpose.

Irwin’s relationship with Beckett, whom he deems “the famous Irish writer of famously difficult writing,” has at times seemed to encompass both love and hate. This makes for a fascinating study of the actor/clown’s progress in understanding his subject and coming to terms with him; he says Beckett’s work has been “huge in my life.” Revealingly he adds about the work, “it may bore others but exhilarates me.” Clearly. And thus proceeding, we arrive at the core of Irwin and Beckett with the driving question, “Is Samuel Beckett’s writing natural clown territory?” What follows in the entirety of On Beckett is the answer to that question.

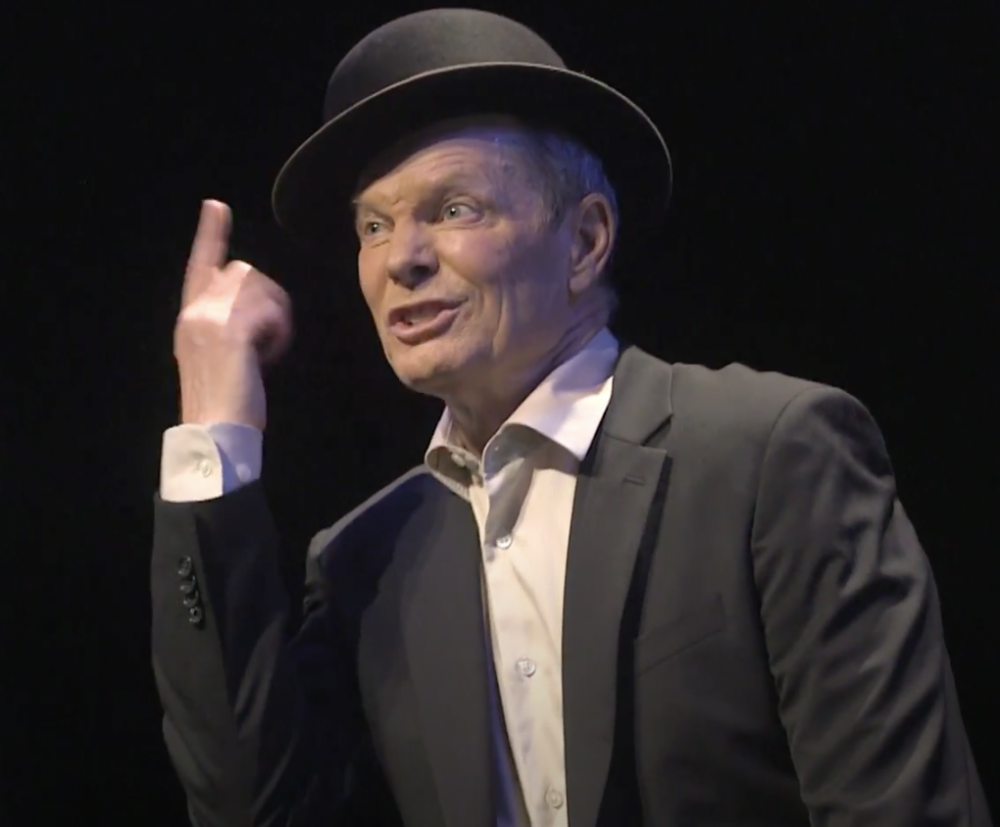

Enter the clown: with a growing array of props, Irwin performs various scenes from the prose work, Texts for Nothing, bringing the language remarkably to life. In his hands, these monologues become wondrous dialogues. From Beckett’s novels, The Unnamable and Watt, the magic of his storytelling is palpable. At times, Irwin’s delivery is musical, like a vaudevillian’s imitation of Dr. Seuss. In each case, the dramatic essence is extracted with exquisite finesse and insight.

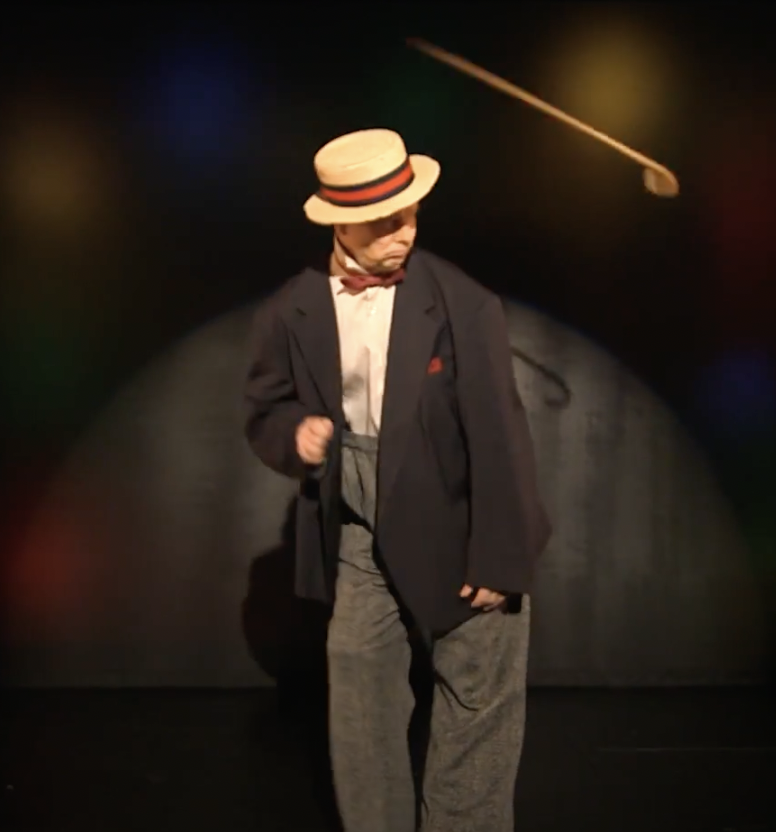

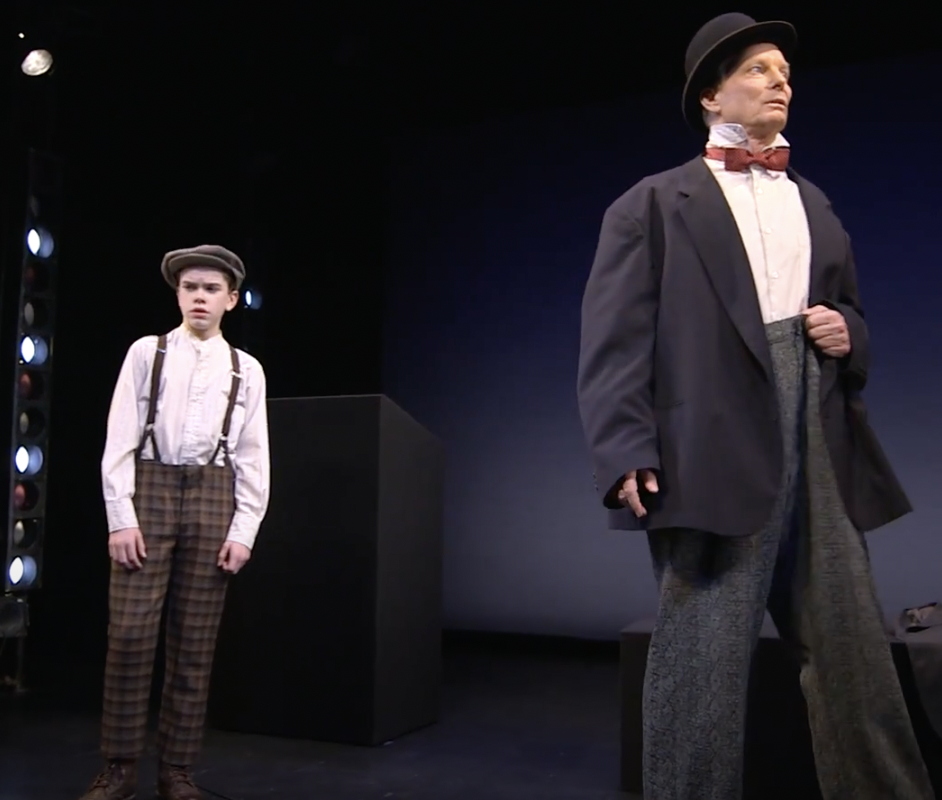

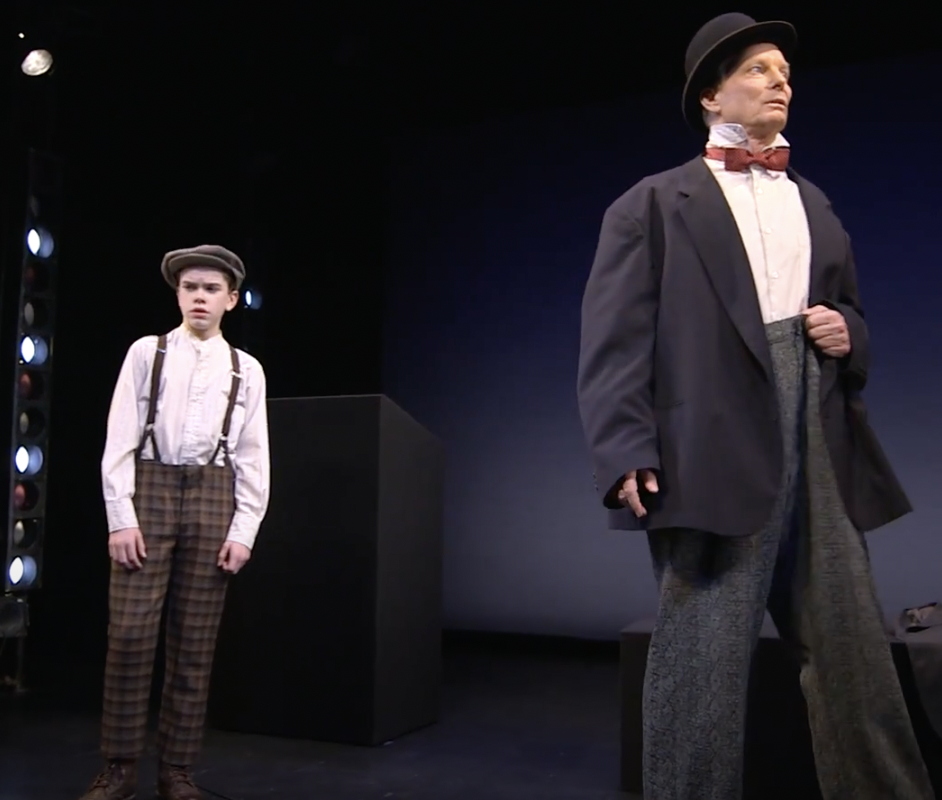

The payoff of On Beckett comes with the famous work we’ve been waiting for, the play, Waiting For Godot. Costuming and props come to the fore. With the several pieces of text he recites from the play, the costuming becomes more elaborate, in a process Irwin refers to as “clowning up.” The trousers become baggier, the hats funnier. Irwin speaks poetically of “the language of hats.” Here is Irwin the clown, actor and interpreter of Beckett in full bloom, the multiple levels of storytelling on display in costume, the choreography of movement, incisive understanding of the text and all of the psychological underpinnings that make the entire exercise work. Irwin’s explanations of Waiting for Godot come with anecdotes of his experiences in playing it on stage as well as snappy synopses of its meaning. It’s enthralling and purely captivating.

By the end of On Beckett, not only have we been massively entertained by a master, but this theatrical journey through the work of Samuel Beckett makes him as much an old friend to us as he is to Irwin. It’s quite a trip and one well-worth taking.

On Becket was conceived and performed by Bill Irwin and directed for camera by M. Florian Staab and Bill Irwin. Charlie Corcoran created the atmospheric scenic design. Michael Gottlieb designed lighting and music, sound design and mix were by M. Florian Staab. Brian Petchers edited.

www.IrishRep.org – last performance streamed March 7, 2021