By Carol Rocamora . . .

Theater history was made this week when a new Stephen Sondheim musical opened at The Shed, New York’s exciting new cultural center.

It’s a cause for celebration, not criticism. So permit me, please, to mark this momentous occasion, rather than critique it.

Considered the greatest musical theater composer of our time, Sondheim has provided us with great works for over a half-century—from A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1964) to great works like Company (1970), Follies (1971), A Little Night Music (1973), Sunday in the Park with George (1984), Into The Woods (1987), and many others. Since his death in November 2021, our stages have been filling with thrilling revivals of his other great works, such as Sweeney Todd (1979) and Merrily We Roll Along (1981) in New York, and Old Friends (a Sondheim revue) and Pacific Overtures (1976) (soon to open) in London.

And now comes “the final Sondheim,” the last of his works to be premiered—this time, posthumously. Here We Are has been years in the making: more than four decades after frequent collaborator James Lapine first suggested the idea, a decade after Sondheim and writer David Ives started to work on it intensely, and nearly two years after Sondheim’s death on Thanksgiving night in 2021. Approved by Sondheim for production before he died that year, his collaborators David Ives and director Joe Mantello continued to work on it after his death.

The seminal idea is both exotic and daunting—a musical inspired not by one, but two films by Luis Bunuel (considered a master of surrealism). Act One is based on the plot of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), wherein a group of six upper-middle-class friends make repeated attempts to sit down and dine together, but are constantly frustrated in their efforts. Act Two is based on Exterminating Angel (1962), wherein another group of privileged people are trapped in a room of a luxurious mansion and can’t get out (although all they have to do is open the door and leave).

Critic Frank Rich wrote a fascinating, comprehensive article in New York Magazine (August 28, 2023) entitled “The Final Sondheim” about the collaboration between Sondheim, David Ives, and Joe Mantello that brought this work to life. The article includes excerpts from their conversations and email correspondence along the musical’s “often tortured path to completion,” in Rich’s words. As David Ives described it, he and Sondheim merged the settings of the two films and featured the same set of six friends from Discreet Charm throughout (plus a few they pick up along the way). In Act One of Here We Are (entitled “The Road”), they drive around looking for a place to dine together. “Buy this perfect day,” they sing brightly, as they journey from restaurant to restaurant, till they finally have a banquet in the luxurious embassy where one of the group’s members is the ambassador. However, in Act Two (“The Room”), they become stuck in a drawing room of that embassy and can’t seem to get out. One by one, they unravel. How do they return to the road, the play asks?

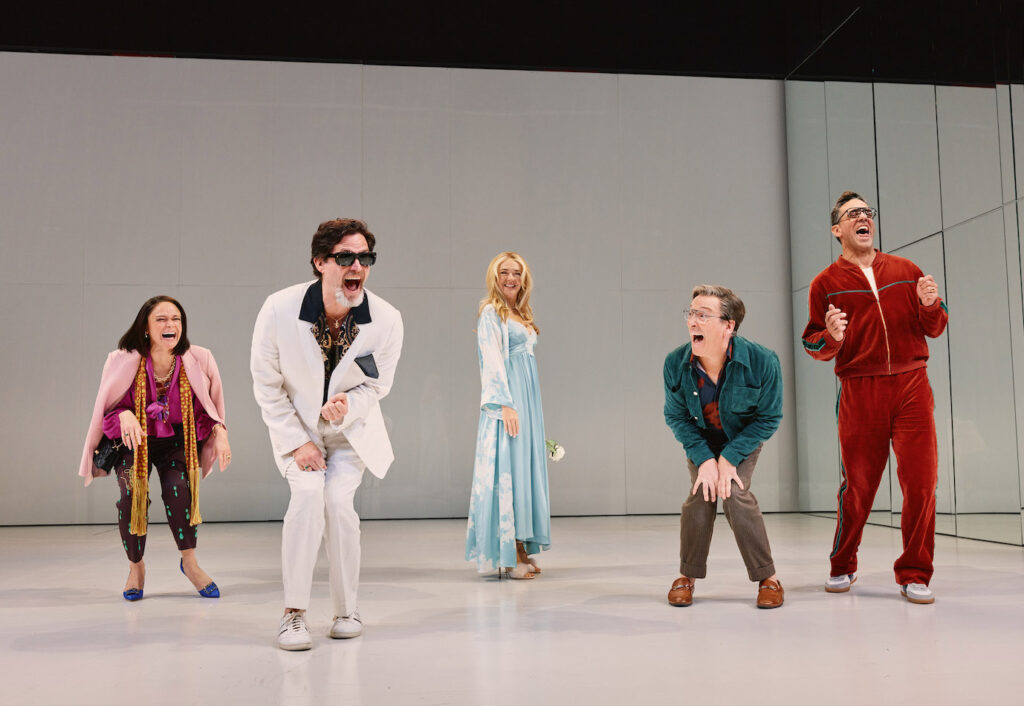

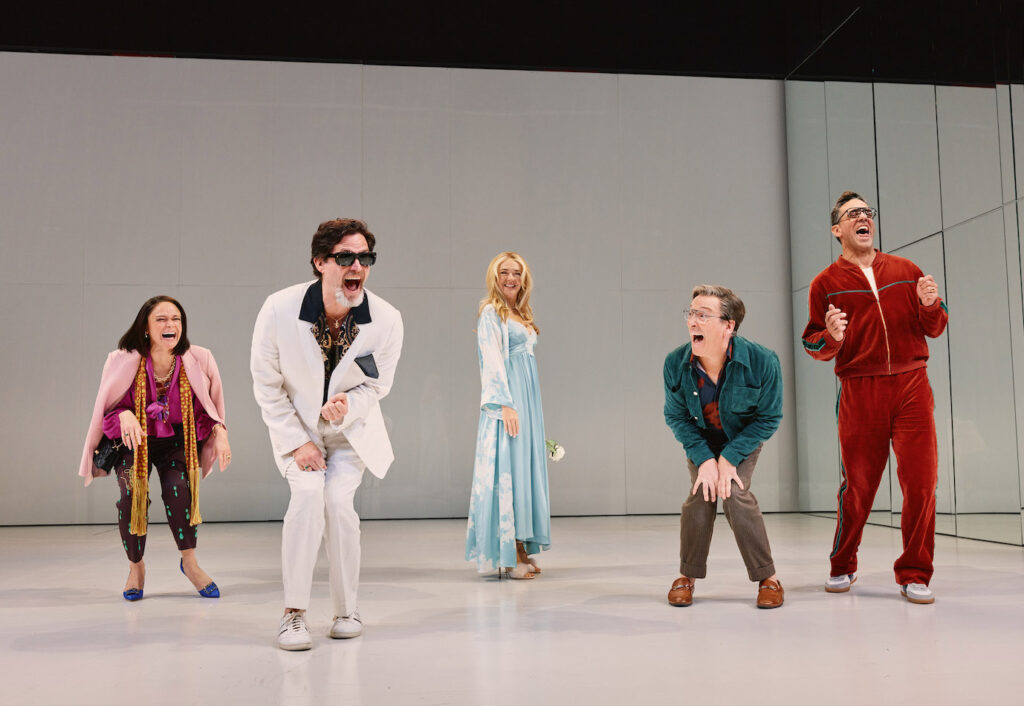

Throughout Here We Are, the collaborators kept the surreal, absurdist tone of Bunuel’s seminal work—to great effect. Working titles of this ambitious new work have changed over the years of development, from “Bunuel” to “Square One” or even “Let’s Eat!” Mantello has assembled a stellar ensemble of actors to play the roles. Bobby Cannavale leads as the successful businessman Leo Brink with his trophy wife Marianne (Rachel Bay Jones); Micaela Diamond plays Marianne’s rebellious younger sister; Steven Pasquale portrays a slick ambassador named Raffael (from a fictional small country); Jeremy Shamos plays a plastic surgeon celebrating the completion of his thousandth nose job (for people who didn’t need one), while Amber Gray is his aggressive agent-wife. Other characters appear along the way including a colonel and soldier (Francois Battiste and Jin Ha, respectively), and a Bishop with a shoe fetish who is looking for a new job (a hilarious, show-stopping performance by David Hyde Pierce). Denis O’Hare steals the show playing multiple roles of a different waiter at every one of the restaurants that the ensemble visits in search of a meal (they can’t find one). In Act Two, set in the embassy, O’Hare transforms into a demonic servant who rules the inferno wherein the characters are trapped.

The production values are dazzling. Joe Mantello’s smart, stylized direction of this stellar ensemble is a joy to behold (enriched by Sam Pinkeleton’s imaginative choreography). Mantello gathers them in designer David Zinn’s sleek empty white and gray box, polished to perfection by the servants (O’Hare and Tracie Bennett). “Why are you here?” asks Leo and Marianne Brink, addressing a group of uninvited guests to a brunch they hadn’t planned. Bewildered, the Brinks then proceed to pile their hungry guests into an imaginary car in search of the ideal brunching place. “Buy this perfect day,” they sing brightly to Sondheim’s initially buoyant score, sparkling with melodies reminiscent of previous shows. One by one, restaurant marquees with names like “Café Everything” and “Bistro a la mode” descend magically from the theater ceiling, only to disappear after the disappointed diners are informed (by the same waiter in different costumes and wigs) that there’s no food at all, not even water. Zinn’s design tour de force comes at the end of Act One, when Raffael invites them to dine at his embassy, and the set is magically transformed into a stately building with a magnificent dining hall.

The ensemble reemerges in Act Two on another stunning set (the elegant drawing room of the embassy). But this time, they’re trapped in it. They may be sated from their sumptuous supper, but they awake to a grim reality that there is no way out of the black, gilded room in which they find themselves. Each character begins to unravel in the threatening, apocalyptic atmosphere. Instead of song, we get verbal laments from each of them on how they’ve wasted their respective lives. Chaos ensues, as the play sinks deeper into a dark inferno until Fritz spontaneously asks: “Can someone tell me what went wrong?” “Brunch!” replies Raffael. With that sudden, unexpected reversal, the collaborators provide a turn-around ending, with the sound of Sondheim music restored.

Here’s a footnote to the previously described Act Two: According to Rich’s article, Mantello and Ives had come up with a concept that Act Two should feature each character offering “a kind of prose equivalent of a song”—meaning an absence of music that they pointed out was also notable in Bunuel’s Exterminating Angels. Mantello wanted the characters “to speak,” according to the article. As a result, suddenly there’s no Sondheim.

Bunuel’s classic films offer a satire on the values of the ruling (bourgeois) class, and the collaborators of Here We Are have retained and expanded that theme. The characters are on a journey through life, trying to find satiety through perfection, as represented by a perfect meal. As a result, they become trapped on the road of their own making, which directs them to the brink of death. Could this hunger also be a metaphor for the collaborators’ desire to help Sondheim finish his final musical (he died at 91), while being trapped by COVID in their efforts?

Throughout the interview with Frank Rich, Ives and Mantello repeatedly refer to their “weight of responsibility” in helping to bring Sondheim’s final work to light. During their most intense period of collaboration—from 2016 to 2021, when Sondheim died—Ives and Mantello describe the bumpy road (there’s that metaphor again), often blocked by Sondheim’s tendency to procrastinate and intensified by the pandemic. Said Ives: “Probably in [Sondheim’s] mind he may have felt that there was work to do on it, as there always is. And so, in his mind, he would describe it as being unfinished.”

Meanwhile, reviewers have been informed that the producers of Here We Are are not submitting it for awards this season (including Outer Critics Circle and Drama Desk). This may indicate that the collaborators plan to keep developing it. My own personal hope is that they will rethink their idea of substituting music with prose in the second act—an idea that Sondheim had approved before his death but may be worth re-evaluating. Instead, they might enlist the great Jonathan Tunick, Sondheim’s orchestrator, to adapt music from the first act and fill those empty stretches in Act Two where there is none. Judging from Tunick’s phenomenal contribution to Sondheim’s oeuvre over many years and brilliant collaborations, it feels like the natural next step.

Meanwhile, for lovers of Sondheim and musical theater, it is imperative to see this vibrant production of Here We Are at The Shed, filled with vitality and creativity. What a thrill it is to take this continuing journey with the “Final Sondheim”! In addition to the definitive contributions of Ives, Mantello and Tunick, there have been many others along the way, including Oskar Eustis who originally developed it at the Public Theater (in 2012); readings with Kelli O’Hara (2017) and Bernadette Peters and Nathan Lane (2021). And now there is an all-star cast team of theater artists (actors, director, designers) who shine.

We’re experiencing theater history in the making, and that’s a privilege.

Here We Are. Through January 21, 2024, at The Shed (545 West 30th Street, between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues). www.theshed.org

Photos: Emilio Madrid