Theater Review by Michael Dale . . . .

As an actor, director, playwright, and teacher, Austin Pendleton’s sextet of decades as a mainstay of American theater, film, and television can certainly be summarized as no less than an extraordinary career. And yet, when I need to explain to people exactly who he is, nothing turns a blank stare into an immediate smile of recognition faster than saying, “He was the original Motel in Fiddler On The Roof.”

And perhaps that defining of a career by a role he played 60 years ago at age 24 serves as a connection between Pendleton and the title character of his intriguing and insightful play Orson’s Shadow, which played Off-Broadway in 2000 and is now running at Theater For the New City in a production he directs.

The Orson in question is Orson Welles, who, back in the 1970s, teenage me primarily knew as that distinguished and well-spoken gentleman in a series of commercials for Paul Masson Wine (“We will sell no wine before its time.”) in the company’s attempt to enhance their low-end product with a more upscale image.

But generations before me would quickly recognize Welles as the 25-year-old genius who directed, co-authored, produced, and starred in his cinematic debut, Citizen Kane, the 1941 drama that to this day is still considered one of the great classics of the screen.

While Pendleton’s career is still going strong—receiving Broadway accolades just two years ago for both his performance in Tracy Letts’ The Minutes and his direction of Stephen Adly Guirgis’ Between Riverside And Crazy—the Orson Welles of his play is a bitter 45-year-old who bristles at compliments for Citizen Kane, regarding them as reminders of that shadow of his youthful success that he’s continually failed to match.

Perhaps my favorite part of the play is that it’s narrated by a friendly and benevolent theater critic. The year is 1960, and Kenneth Tynan (shy, but genial Patrick Hamilton) has been a journalistic champion in encouraging the emerging movement of contemporary working and middle-class realism permeating London’s stages. A major beneficiary of his praise has been Look Back In Anger dramatist John Osborne.

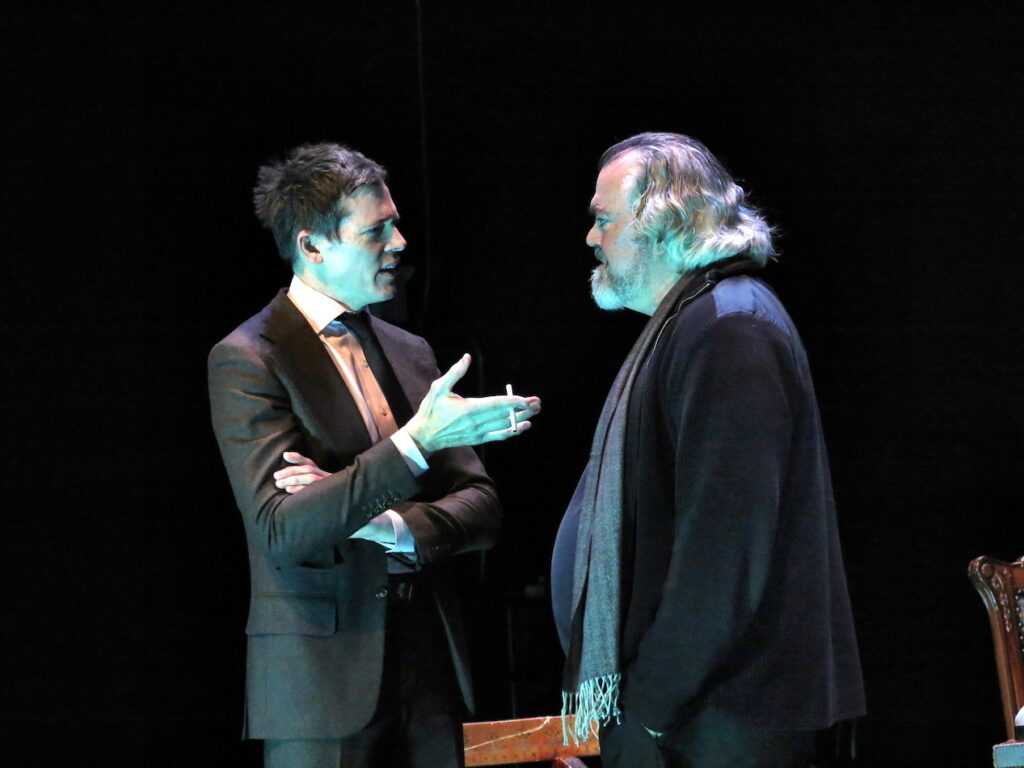

One of Tynan’s idols, Sir Lawrence Olivier (impeccably groomed but anxious Ryan Tramont), has recently triumphed playing a music hall performer whose act is aging faster than he is in Osborne’s The Entertainer, and the journalist wishes to be involved, in an advisory capacity, with Olivier’s formation of the National Theatre of Great Britain. To that end, he convinces Welles (Brad Fryman, displaying gruff and earthy arrogance) to direct Olivier in Eugene Ionesco’s new allegorical drama, Rhinoceros, about a town where everyone is turning into the titular creature.

Welles doesn’t like the play, but he needs money to finish his new film. Olivier doesn’t understand the play but sees his style of classically trained elegance falling out of fashion and he wants to adapt.

Perhaps symbolic of this falling out of fashion is Olivier’s divorce from Hollywood star Vivien Leigh (understated Natalie Menna) and his new relationship with the decidedly less glamorous and more intellectual Joan Plowright (Kim Taff).

Rhinoceros is probably best remembered in America for Zero Mostel’s Tony-winning performance where, through the course of one scene, he believably transformed himself into a snarling, raging rhino in front of the audience without the use of makeup or prosthetics. But that’s a supporting character. The lead role Olivier is meant to play is a timid, confused Everyman, a part the star is exceedingly uncomfortable with, and he tries to convince his director to let him play it in a showier, more assertive fashion.

While the two men fight for artistic control of the project during a rehearsal, Taff’s Plowright quietly gives off an air of patience and competence, expertly adapting to the changes they throw at her.

The only non-celebrity character is Welles’ assistant, Sean, played with carefree amusement by Luke Hofmaier.

If the versions of Orson Welles, Lawrence Olivier, and Vivien Leigh that Pendleton essays for Orson’s Shadow are starting to feel like ancient artifacts in 1960, the extreme cultural and artistic changes of the next decade would only confirm their dread. While the play can be enjoyed as a juicy portrait of lions in winter doing what they can to remain relevant, it’s also a reminder of the inevitable changes in taste that time always brings; and how eventually every generation’s revolutionary concepts must make room for their childrens’ newer ideas.

Orson’s Shadow. Through March 31 at Theater For The New City (155 First Avenue between East Ninth and Tenth Streets). Running time: two hours with an intermission. www.theaterforthenewcity.net

Photos: Jonathan Slaff