By Carole Di Tosti. .

As we age, are we flexible enough to embrace our life’s painful realities? Do we learn or do we arrive at fearful events to wonder how and why? Or in hindsight are we filled with regrets and recriminations, unable to give voice to our experiences?

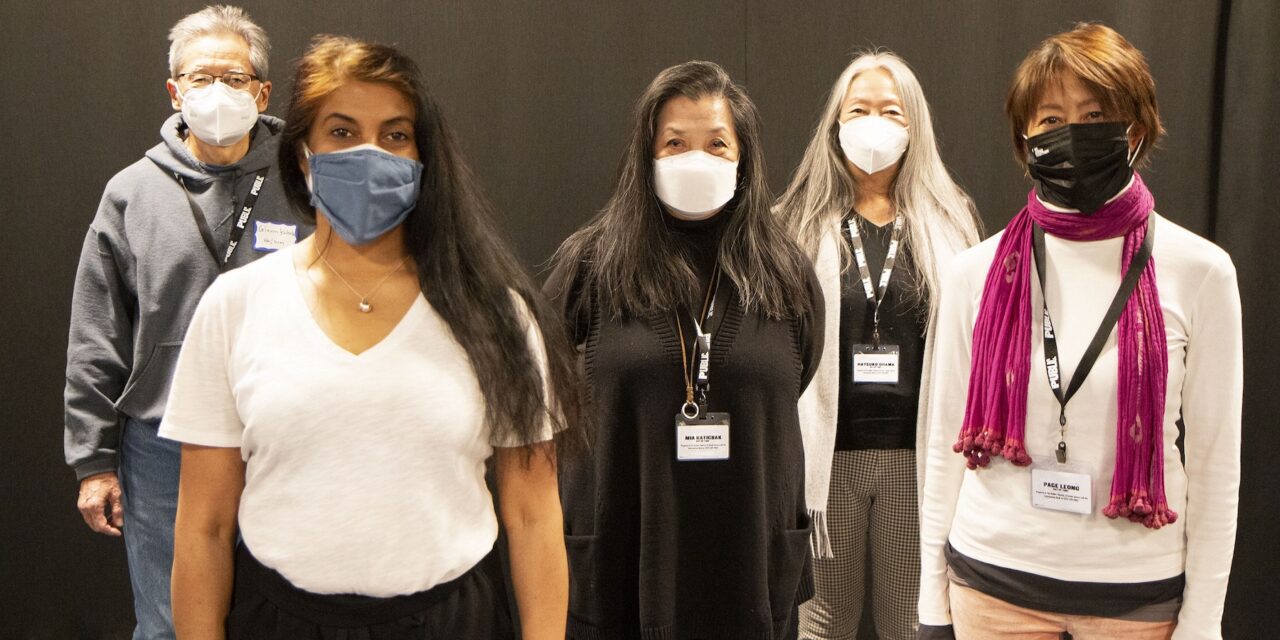

Out of Time, a program featuring Asian-American writers and actors confronts such questions about age through the wisdom gained by living. Conceived and directed by Obie Award-winning director, Les Waters, the production is a collaboration between the National Asian American Theater Company and the Public Theater. It is running through 13th of March.

The production is a vital offering that presents the distinctive and powerful voices of Asian Americans over the age of sixty in five newly minted solo works by award-winning Asian-American playwrights. In the monologues the playwrights codify their veterans of life’s experiences with vitality and depth, and they use stories and meditations heightened by the characters’ memories and insights.

This vibrantly hued mosaic is brought together with the unique lyricism of four women and one man and brought to life by the superb acting ensemble. Playwrights Jaclyn Backhaus, Sam Chanse, Mia Chung, Naomi Iizuka and Anna Ouyang Moench use the lens of time past, in the present circumstance to examine issues of ancestry, love, loss, identity, personal evolution and dissipation into regret.

In the first presentation “My Documentary,” written by Anna Ouyang Moench and performed by Page Leon, a savvy-looking women walks with poise and dignity onto the stage of transparent cream-colored curtains staggered in an arrangement for maximum flow (the set throughout the program). The woman introduces the subject of sweaters, quipping about her handmade ones which no one “really wants,” though they may say otherwise. With humor and grace, she segues to her life story and love for her family and husband Peter, and then she settles surprisingly on the point that she is a documentarian. Interestingly, focusing on others with an objectivity, her subjects have been wide-ranging. And as she comes to the end of her life’s meditation, she reveals that she has not left time for her own life’s realizations. When something occurs, the remorse drives her to create her own documentary which no one wishes to fund except herself. An ironic conclusion to validate her love and regret.

In Mia Chung’s play “Ball in the Air,” the emotional undercurrents from the first monologue switch to the lively action of Mia Katigbak, engrossed in playing with a paddle ball that she smacks repeatedly hitting the red ball attached to a “string.” The point is the optical illusion of what she appears to be doing. But in effect she is distracting us and herself. The distraction continues during the monologue that turns into a series of fragments of meaning about a friendship betrayal, a lost election, a bike accident, a car crash and an email that freezes her emotions from the closeness she once felt with a friend. We are reminded of our memory, fragmented by feelings, unable to be logically related so that others understand us. And on the surface, we keep the ball in the air, not actually knowing for ourselves what is real, what we hide from ourselves and others, and whether we can figure it out ever, or remain in confused uncertainty.

Jaclyn Backhaus’s “Black Market Caviar,” is a fascinating meditation delivered on the screen by Rita Wolf who the director staged behind the set’s sheer curtains, so we see her sitting in a chair upstage right in profile yet witness her film presence up-close and personal. The occasion is a mother’s revelation of ancestral heritage of disease inherent in her body’s DNA in the eggs she carries. Rita Wolf’s performance is screen worthy. The close-ups of her face register every emotion, every nuance of feeling that she renders beautifully, authentically. Carla’s (Rita Wolf) loving message is spoken to her younger self 30 years in the future and to her children.

As she discusses the genetic predisposition in a woman’s eggs toward cancer passed to her from her grandmother to her mother, she relates the fear of this secret which she found out from her mother having cancer. The secret was hidden and expressed almost as an afterthought. Buried truth intensifies fear and traumatizes. Thus, to overcome the thought that her DNA most probably holds cancer cells, she becomes playful about tasting the briny caviar of Sturgeon eggs, aligning that caviar with her own eggs. We are as heartened as she to hope she will be alive to see the film in the future, knowing that she “was afraid, but she lived her life.”

The last two monologues are powerful. Naomi Iizuka’s “Japanese Folk Song,” stars Glenn Kubota as a silver-haired retired banker named Taki who speaks to his grown daughter about his life. Ohama Chanse’s “Disturbance Specialist,” stars Natsuko Ohama as Leonie who gives a lecture to her alma mater. In the monologues lighthearted humor contrasts with ironic defensiveness and remorse. Though redemption is sought, it is never adequately received.

In “Japanese Folk Song,” Kubota’s charming Taki draws us in with humor as he relates his life. However, he awakens to his current reality with a jazz song which he hates, and which is based on the song “Kōjō no Tsuki.” Recalling this song reminds Taki of a current betrayal from which there is no escape. In “Disturbance Specialist” educator and activist Leonie finds herself cancelled from her eventful, renowned life because of an unfortunate tweet. Moving between defensiveness and bravado, self-recrimination and acceptance of accountability, Ohama’s Leonie falls in disgrace. It is an unfitting end from which she may never recover at this age in her life.

Out of Time is an amazing evening at the Public. Kudos to the creatives: DOTS (scenic design), Mariko Ohigashi (costumes), Reza Behjat (lighting design), Fabian Obispo. Running time is 2 hours 30 minutes. Tickets: https://publictheater.org/productions/season/2122/out-of-time/

Photos: Billy Bustamante

Lead Photo: Yuko Kudo