by Cooper Lawrence

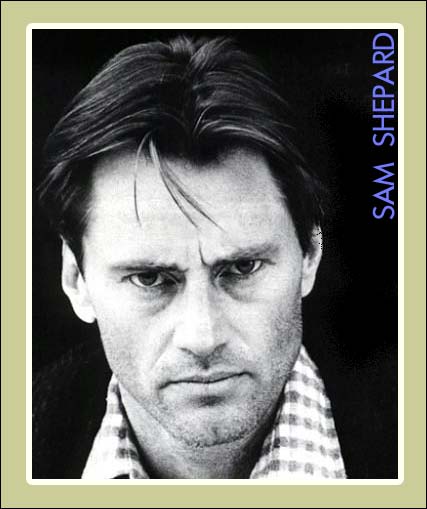

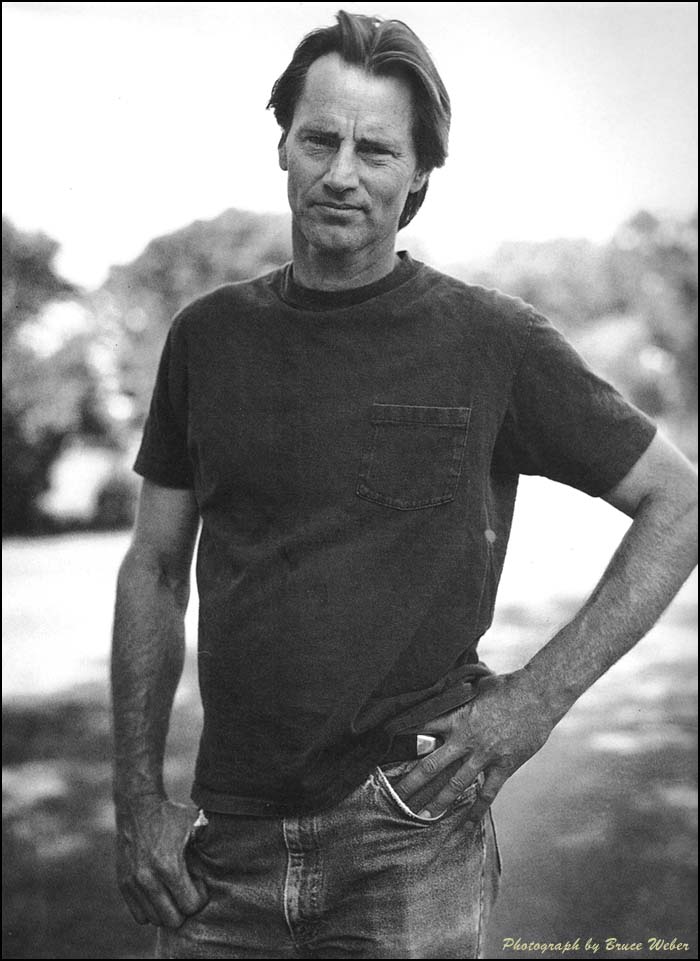

Sam Shepard, Pulitzer Prize winning, and Oscar nominated playwright, actor and director has died at the age of 73.

To many of us who have been—or still are—in the theater, he was known as an icon who changed lives with his art. Shepard died from complications after suffering with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) for some time. He passed away peacefully at his Kentucky home, Sunday, surrounded by his sisters and three children.

Shepard made his mark with edgy, bleak, and extremely dark stories about American middle class life. His real father, a terrifying alcoholic with a very short fuse, became a recurring character in many of Shepard’s plays as if we were in on his uninterrupted attempt to exorcise those demons.

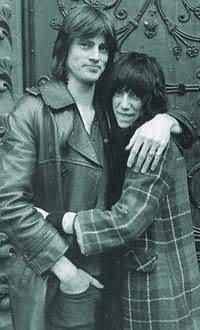

In 1971, one of Shepard’s early mentors, Wynn Handman, staged Shepard’s Cowboy Mouth—a collaboration with then-lover Patti Smith—at Handman’s American Place Theater.

But it was an earlier play of Shepard’s, La Tourista (1967) that Handman tells the story of a young, shy, Shepard:

Shepard did not want to be part of the casting process, allowing Handman to do as he pleased; so he read a little known actor named Sam Waterston in the role of Kent. During Waterston’s audition a rumbling came from under the bleachers and a faint, familiar voice whispered, “cast him.”

In 1979 Shepard won a Pulitzer for Buried Child and was dubbed “The greatest American playwright of his generation” which he certainly was. Shepard racked up awards, nominations and accolades for decades as a writer, actor and director.

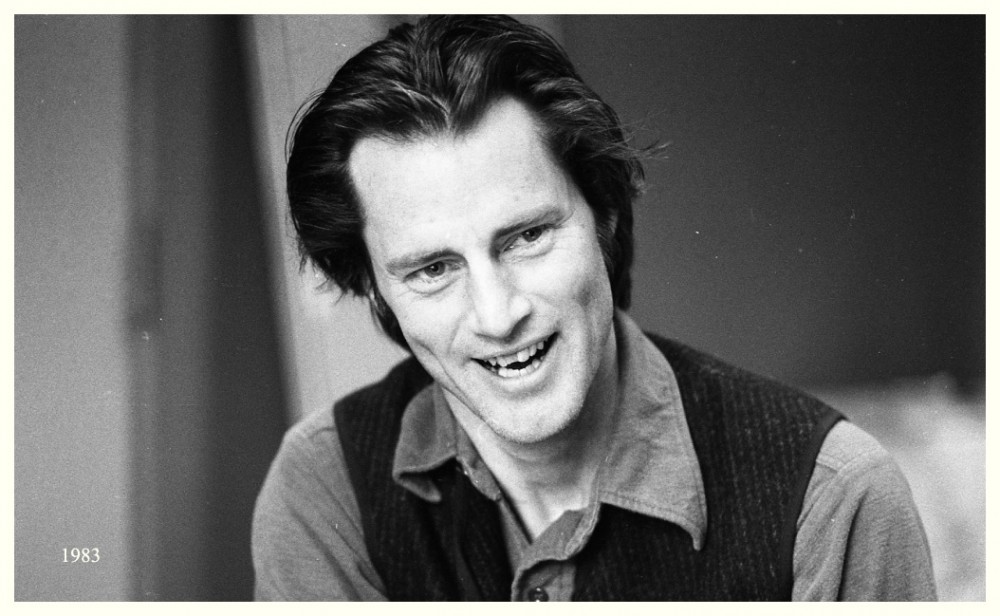

Some memorable work includes the Tony nominated, True West (1980), Curse of the Starving Class (1978), Fool For Love (1983), A Lie of the Mind (1985) and Simpatico which played at the Joseph Papp in 1995 and starred Ed Harris, Marcia Gay Harden, Beverly D’Angelo and Fred Ward.

Shepard’s most recent work was as an actor playing the patriarch of a troubled Florida family in the Netflix series Bloodline.

For lovers and scholars of Sam Shepard’s plays, it is widely known that Shepard’s writing philosophy has always been, “come late; leave early.” Thus, a play would begin in the middle of a situation, a thought, a scene, or an action as if we (the audience) had rudely interrupted them. So, too, would the plays end without full resolution or as if there is more left to be said.

Sadly, this philosophy, embedded in his writing has also become true to his life. At 73 he not only left us too early, but surely he had much more to say.