By JK Clarke

If you’ve seen the latest Cohen Brothers film, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (Netflix), you’d hardly expect that the actor playing the title character, Tim Blake Nelson (who also starred in O Brother, Where Art Thou?), penned the fascinating and complex new bio-play Socrates (now playing at the Public Theater through May 26), an in-depth telling of some of the life and a lof the death of the world’s most renowned philosopher. But, neither looks nor roles are everything, and indeed Nelson, the Tulsa, Oklahoma native who was an accomplished Ivy League student of Classics and Philosophy,has managed to pull off a thoughtful and provocative biographical sketch of one of the greatest philosophers of all time.

The device by which Socrates’ story is told is a sensible one. A young acolyte, referred to as “A Boy” and played by Niall Cunningham (who so strikingly resembles a Greek statue that if you drenched him in white paint and ordered him to stand stock still, you’d be hard pressed to tell him apart from one) is being taken under the wing by the legendary philosopher and writer Plato (played with reverence by Taegle F. Bougere) as a favor to a friend, on behalf of the lad’s deceased father. The Boy, a headstrong and argumentative teen, regards Plato cynically for the role he perceives Plato and others had in Socrates’ demise—he was put executed for, among other things, “corrupting the youth,” with his execution taking the form of his drinking a potion of poison hemlock. He, in fact, believes Socrates’ entourage should have done everything they could to save the great thinker’s life, but didn’t: “The Athenians killed him. My question therefore implicates you, especially in the context of a democracy where leaders and their actions . . . [represent] the people’s will.” Socrates friends, too, in the boy’s view, may as well have been his executioners, since they were present at the philosopher’s death, as recounted in Plato’s writings. In order that the boy (and, hence, the audience) might understand fully what led to Socrates’ death, Plato takes him back in time to witness scenes of Socrates’ life, in which groups of aristocratic, inebriated men talk, laugh and argue. The boy takes place in these scenes, standing in for Plato.

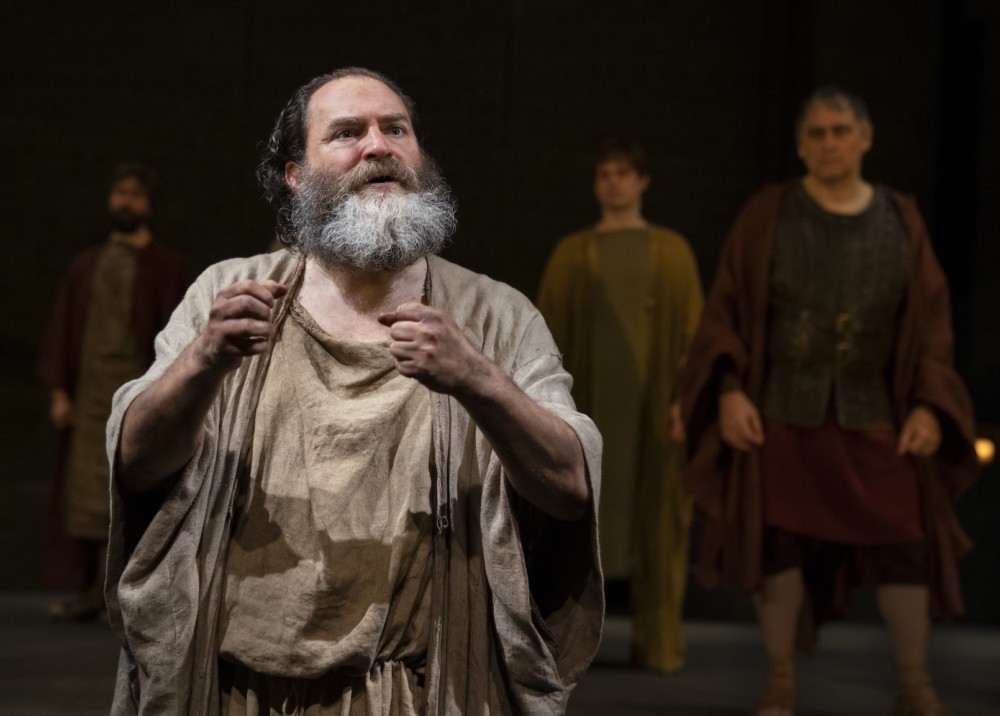

Michael Stuhlbarg, Austin Smith

In the opening flashback, Socrates (fabulously played by Michael Stuhlbarg, who brings to mind here, in look and tone, a relaxed and sane Robin Williams in The Fisher King) interacts with the celebrated general Alcibiades (Austin Smith), “the physical and mental embodiment of all Athens stood for,” as others stood by, laughing and chiming in, as the two debated the notion of Love. It’s made clear that while Socrates is a voyeur, “obsessed with good looking boys,” and that although homosexual interactions between men was in no way taboo (at least among this group), Socrates never physically participated, despite Alcibiades’ pleading and even attempting to physically manipulate him. This eventually goes to disproving (to the audience and the Boy anyway) the idea that Socrates was a “corrupter of youth.”

What the men chiefly complain about is Socrates’ ability to manipulate others with words, and ceaselessly argue. Ultimately we learn that he is a lover of knowledge, thought and the ability to question and examine all issues from all angles. That he would wander the city talking to (heaven forfend!) tradesmen and working class citizens of all social ranking. One could argue that this, ultimately, is what helped cause him to fall from favor. But, more importantly a Populist rebellion against “elitists” (sound familiar?) led to spiteful revenge against the intellectuals and aristocrats. As a visible symbol of that group, Socrates is put on trial. Antyus (David Aaron Baker), a “tanner of hides” suggests that Socrates and his followers “have desecrated [the] government and our God, ridiculing both with an arrogance that has delivered ruin.” This, of course, is a specious argument in a supposed democracy, but Socrates is nonetheless convicted. His refusal to either make statements contrary to his own beliefs nor use his friends’ money to flee into exile (which he views as hypocritical) doom him to an unnecessary, but certain death.

The discussions surrounding Socrates’ death and arguments about the meaning of a Democracy or a free society could go on for hours longer than the two and half we witness on stage. And despite the intellectual curiosity they arouse, they are also somewhat somnambulic, a problem with which the play must constantly battle. Largely, the play succeeds for being informative and engaging, but not necessarily for all audiences. Despite fine performances and staging, it takes a special kind of personality to remain fully engaged through any such discussions.

It is largely thanks to director Doug Hughes that Nelson’s compelling but complex script is so easily digestible. But Scott Pask’s set (of walls inscripted with Pericles’ funeral oration), Tyler Micoleau’s gorgeous lighting, Tom Watson’s wig design and Catherine Zuber’s authentic costume design give us the impression that we are actually witnessing a scene in ancient Greece, flies on the wall watching all these discussions take place. At times the scenes look like live-action tableaux vivant with some characters, like Aristophenes (Tom Nelis) looking shockingly realistic, plucked from the cover of a Greek literature textbook.

Philosophy is not one of those subjects one can bump up against lightly. A discussion of, say, the purpose of morality, is not easily dismissed with a few casual comments. In fact, almost by definition, such a discussion almost assures sharp disagreement, circular argument and continually regurgitated, digressive theses. And this is precisely why a play about philosophy and philosophers is dangerous territory. But Nelson, Hughes and company manage to grapple with the subject so skillfully that we walk away from Socrates not only deeply informed, but passionately entertained.

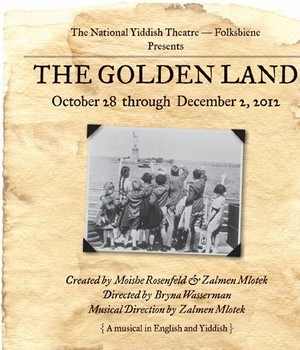

Socrates. Through May 26 at The Public Theater (425 Lafayette Street at Astor Place). Two hours, 45 minutes with one intermission. www.publictheater.org

Photos: Joan Marcus