By Marilyn Lester . . .

When you want to hear a rousing variety of jazz music and simultaneously learn about one-hundred years of jazz history, who ya gonna call? Why, the Anderson brothers of course. The two, identical twins Will and Peter, have a performance specialty—putting together entertaining presentations combining visuals and narrative and, of course, plenty of swinging music. In their latest such venture, The Journey of Jazz at 59E59 Theaters, the two have upped their game. Ninety minutes without interruption ends with patrons still wanting more.

The brothers bring to the table a keen appreciation of history and the need to communicate it; they’re educators on and off stage, and that mission can’t be underestimated. They also have a terrific sense of fun and that translates in their presentations. Who else would offer a clip from the 1984 mocumentary, “This Is Spinal Tap,” and master of malaprop and baseball great Yogi Berra’s take, to help answer the question, what is jazz anyway? The entire enterprise is backed up by virtuosic musicality. Will and Peter are masters of the reeds; Will plays alto and baritone saxes, flute and clarinet. Peter plays tenor and soprano saxes and clarinet. And what they’ve been consistently brilliant at in their work is arranging any given piece with a fine-tuned ear to applying the range of these instruments to the number at hand.

The journey began with Scott Joplin’s 1899 “Maple Leaf Rag,” with versatile pianist Dalton Ridenhour on the keys, leading directly to Nick LaRocca’s 1917 megahit, “Tiger Rag,” a piece that continues to be recorded today, and which remains an all-time favorite for musicians to transmute in contrafacts by riffing on chord changes. Whereas in their programs that focus on a single theme, and in which the brothers offer real-time narrative with film clips, in The Journey of Jazz, that function was executed in a pre-recorded film with script, narration and video production by Will. Although some slides were difficult to read, the ultimate goal of adding context to the music was achieved. However, more movement and live text would have added more zest to the show, which also had a lighting plot by Janie Johnson that seemed ironically improvisational.

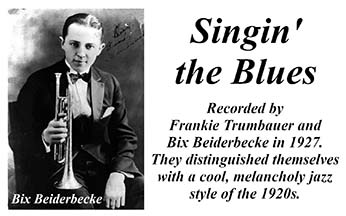

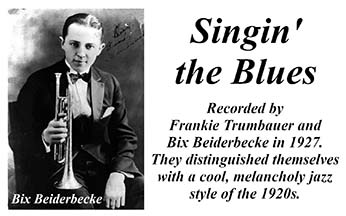

Anyone who knows jazz will realize what a monumental task the brothers took on in identifying the key moments of over a hundred years of jazz and its evolution, as well as its larger impact on national and international culture and identity. Jazz has, as Will and Peter vividly demonstrated, moved within the greater cultural ethos of the nation. In the roaring twenties there was the seminal influence of trumpeters “Bix” Beiderbecke (“Singin’ the Blues”) and Louis Armstrong (“Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” composed in 1927 by Lil Hardin Armstrong). And of course, the energetic music of the era was captured in one of Duke Ellington’s genius compositions, “The Mooche.”

The Great Depression was reflected in jazz music by many big bands that emerged and lifted spirits, not the least of these being The Benny Goodman Orchestra. In 1936, Louis Prima wrote “Sing, Sing, Sing (With a Swing),” which ultimately became associated with Goodman and especially his drummer, Gene Krupa. This tune put a huge spotlight on the show’s drummer, Paul Wells, one of the most intelligent and talented percussionists in the business. Representing clarinetist Goodman in the spotlight, was Will. Peter took his own turn thus on the tenor, with “Body and Soul” (Johnny Green) as played by Coleman Hawkins.

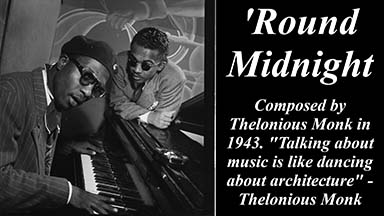

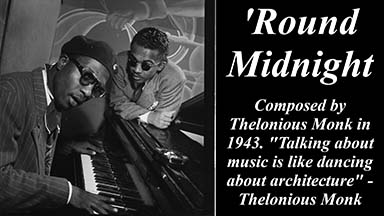

World War II and the post-war years saw another shift in jazz, exemplified by the bebop movement, led by men who have become jazz icons: Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane and Miles Davis, wherein trumpeter Wayne Tucker was featured, using a muted technique made famous by Davis. It was fun to hear the band’s vocalizations on Parker’s “Salt Peanuts” and very illuminating to learn about Afro-Cuban rhythms entering the jazz scene via Gillespie’s trip to Cuba and his composition, “Manteca,” which gave bassist Clovis Nicolas the ability to shine on a melodic solo. The 1950s, an era in which jazz was being somewhat eclipsed by rock and roll, featured the Ellington-inspired pianist, Dave Brubeck and his “Blue Rondo À La Turk.”

There was much more, of course. The last word on jazz, via the video, was given to Duke Ellington—and props to the brothers for that. Most jazz artists know they stand on Duke’s shoulders, a genius of American music (which he preferred to call “jazz”) and constant compositional innovator. Early in his career, Ellington glibly defined jazz as “like the kind of a man you wouldn’t want your daughter to associate with.” More seriously over the years, Duke had deeper thoughts about this music he helped create and define. The clip in the Anderson video featured an interview Ellington had given near the end of his life for Swedish television. Within a few minutes this eloquent, erudite icon had defined jazz and its history, using a tree as a metaphor, and ending with the root of it as the rhythms of the African continent brought to the new world of America.

But the closer was a new work by Peter Anderson, who also wrote all the arrangements for the show. Entitled, appropriately, “Journey of Jazz,” this lightly swinging tune, with shades of Henry Mancini and Neal Hefti, was a happy-making finale to a superlative show. Kudos to the brothers, who created and directed The Journey of Jazz, for their wise choices in selecting the composers, music and musicians both important and entertaining; there was enough in place to entice those not familiar with jazz, or wary of it, to sign on as converts.

The Journey of Jazz, 90 minutes with no intermission, runs through Sunday, December 11 at 59E59 Theaters, between Park and Madison Avenues, on 59th Street in Manhattan. Please visit www.59E59.org for tickets and more information.

Featured Image: The Anderson Bros. (photo: Lynn Redmile)