By Myra Chanin

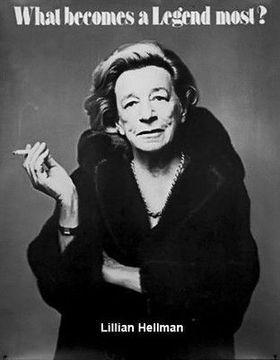

I have always admired Lillian Hellman. She may not ever have served drinks, tits propped up as a Playboy bunny, but she was a total feminist, born way before her time, remarkable:

As the blacklisted icon who in reply to a HUAC subpoena offered to speak truthfully only about her own but no one else’s activities, because she refused to cut her conscience to fit this year’s fashions.

For her intimate, initially sexual, later celibate but always non-connubial partnership with Dashiell Hammett which endured for 30 years including jail time until death did them part.

As the singular senior Legend who posed “as is” for Richard Avedon’s Blackglama Mink ads.

Later, her memoirs mixed fiction with fact. Most people believed she based Julia on psychoanalyst Muriel Gardiner’s experiences helping European Jews escape Nazi oppression. The Most outspoken critic, Mary McCarthy, declared on Dick Cavett’s Show that “every word Lillian writes is a lie, including and and the.” Don’t ask about the lawsuit which followed. It endured beyond the grave when the executors of Hellman’s estate finally withdrew it.

Lillian was no starving artist. Her maternal Granny and Momma were Marx banking heiresses who, by marrying beneath them, to her liquor dealing Zaida (grandfather) and her shoe salesman Dad supplied her with plot and characters for her most enduring play.

She moved to New York, took classes at NYU and Columbia, married The New Yorker humorist Arthur Kober, and was westward bound. In Hollywood, she evaluated potential screenplay material for M-G-M, found the pay good, the work boring but the perks sensational when she first set eyes on her soulmate Dashiell Hammett at a Bing Crosby opening night in 1931. By 1932 Lillian was divorced and back in New York creating well-made, three-act plays with a beginning, a middle and an end. Hammett suggested the subject for her first Broadway hit, The Children’s Hour, in which false accusations of a lesbian relationship between two schoolteachers resulted in unhappy endings for both characters but rewarded Hellman with a Hollywood offer to write screenplays @$2500 a week.

Her most significant and long-lasting drama, The Little Foxes (1939) depicted a greedy, ambitious, Southern family’s march toward millionaire-hood with the greediest, Mama Vixen Regina, portrayed on Broadway by Tallulah Bankhead, you ‘all, and immortalized by Bette Davis (1941) in the film that followed.

Subsequent revivals of Foxes included one directed by Mike Nichols (1967) starring Anne Bancroft and George C. Scott. Next came one helmed by Austin Pendleton (1981) starring the post-Richard-Burton pre-Larry-Fortensky Elizabeth Taylor who filled every seat in the place.

My claim to fame? Seeing Liz’s Regina on opening night in my first comped seat. How? Irving Licht of blessed memory, Philly’s maddest hair stylist, whose clients included Foxes’ producer, Jon Cutler, offered Irving opening night comps if he came to New York and would make Jon look impressive at the fete following the final curtain. I, also one of Irving’s patrons, paid for our club seats on the Metroliner to Manhattan. They were considerably better than the ones Cutler supplied. We finally were seated in the eighth row of Seventh Heaven halfway through the second act.

I am now so starved for live entertainment down in the Corona-virused belt of Delray Beach, FL that when I read the Quarantine Theater Company was doing a live zoom reading of The Little Foxes, starring Austin Pendleton as bad Ben Hubbard, I waved my hand in the air yelling Me! Me! Me!

For openers, Pendleton told an amusing anecdote about the Nichols 1967 revival in which he ended in the cast. Nichols wanted Dustin Hoffman, whom he’d just directed in the forthcoming film, The Graduate, to play the scumbag, callow, young Leo Hubbard, but Dustin shilly-shallied and Austin, who was touted as a similar type, was cast…not by Nichols. Austin’s performance dismayed Nichols. Not how he spoke his lines, but how he moved. Finally, Anne Bancroft figured out the problem. Austin was a smart guy. He considered his brain his most valuable body part, and stepped on stage in every scene with his head thrust out. Leo Hubbard felt that way about his genitals and once Austin managed to walk on stage with his crotch thrust out before his body, peace was restored.

The Little Foxes is brother-sister power struggle between Pendleton’s diabolical Ben Hubbard and Morgana Shaw’s Vicious Regina, his malevolent sister. She’s the wife of the becoming more virtuous banker Horace Gibbons, who is being treated for a serious cardiac condition at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Ben needs banker Horace to invest 1/3 of the capital to fulfill Ben’s dreams of bringing the cotton mill to the cotton and keeping the enterprise under Hubbard family control. Regina, and Horace’s daughter, is sent to bring her father home. Horace is not the man who left. He’s spent his time at the hospital thinking about what he’s accomplished in life and is determined not to help Ben do anymore harm to the people around him.

Who succeeds in getting what they want and how it’s done accomplished is what the play is about.

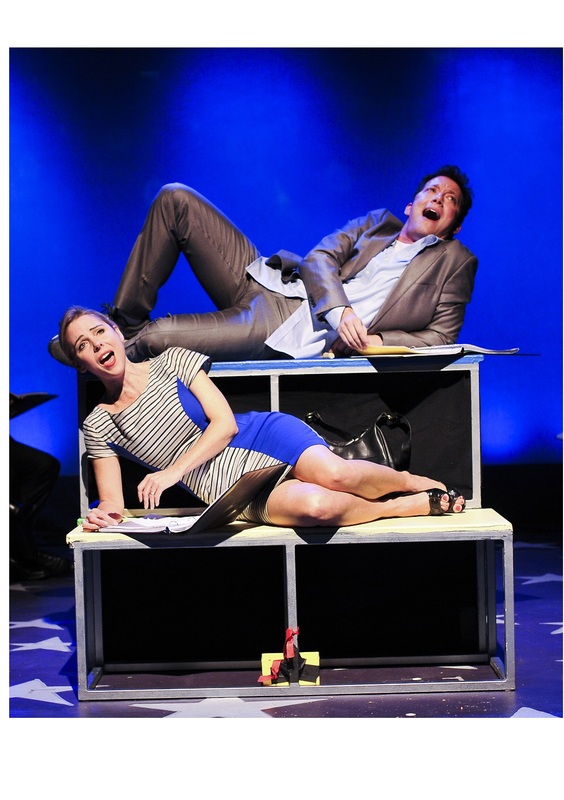

I found Quarantine Theater’s reading uneven. Sound is inconsistent. Voices are muted. Pages of script disappear. While it’s hard for a cast to connect cohesively when the actors are only together on a monitor screen, Austin Pendleton and Tom Smith more than managed to be totally compelling. They are both well worth watching. I cannot praise those particular performers enough. Their artistic truth goes marching on.

The play still proves to be intriguing and very au courant in tone. The Hubbards may have gone to Washington.

As proof that fame is fleeting is the fact that this great American drama is not available in Kindle format. OMG!!!

Quarantine Theater Company’s presentation is available at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCNXgS0lMRsCdWbvNtUKHgww

If you only want to see part of it, watch the second act which begins at 1 hour and four minutes into the program and features both Pendleton and Smith.

To see Foxes at its best, stream the Samuel Goldwyn 1941 film starring Bette Davis and many of the actors from the original Broadway cast.