Theater Review by Samuel L. Leiter . . . .

A brief (but incomplete) timeline: 1900: L. Frank Baum publishes his fantasy novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz; 1903: a hit musical version of the book, The Wizard of Oz, opens on Broadway. 1908: a silent movie of the story is produced; 1925: a silent film with Oliver Hardy as the Tinman opens; 1939: Judy Garland stars in the MGM classic The Wizard of Oz; 1974: The Wiz, an all-Black musical adaptation opens in Baltimore; 1975: The Wiz moves to Broadway, wins seven Tonys, and runs for 1,672 performances; 1978: the movie version opens, starring Diana Ross; 1984: The Wiz is revived on Broadway and flops; 2004: a spinoff adaptation of the story, Wicked, opens on Broadway and, 20 years later, is still running; 2009: a three-week summer Encores! revival opens; 2015: The Wiz Live!, a TV adaptation drawing from both the show and movie is broadcast; 2024: the second Broadway revival of The Wiz opens.

So, ding dong!, the Wicked Witch ain’t dead after all but continues to spread her mischief as young Dorothy, tossed by a Kansas tornado into the magical land of Oz, seeks to find her way home to Aunt Em in Kansas. Joining her on her odyssey to gain help in the Emerald City—ruled by a conniver called the Wizard, a.k.a. the Wiz—are a scaredy-cat Lion searching for courage, a rusty Tinman questing for a heart, and a doofus Scarecrow looking for a brain. To succeed, they must escape the clutches of Evillene, the Wicked Witch of the West, whose equally wicked sister, the Wicked Witch of the East, Dorothy is credited with killing when her tornado-blown house fell on and squashed the witch.

The story’s outline remains the same, but The Wiz, originally subtitled, “The Super Soul Musical “Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” gets much of its sass from expressing nearly every line and character, not to mention its music, in African-American cultural terms. When the show first appeared, its successful all-Black cast and creative team was considered path-breaking.

In its current, problematic iteration, at the Marquis Theatre—a stop on a national tour that began over half a year ago—too much of it is pumped up to ear-splitting decibel levels (worsened by a less-than-stellar sound design). A number of changes have been made to the script, and the titles of Charley Smalls’s souped-up rock, R&B, gospel, and soul songs (apart from Luther Vandross’s “Everybody Rejoice”—he wrote the music and lyrics), vary a bit from the original, including where they’re placed.

Amber Ruffin (Some Like It Hot) has added “additional material” to William F. Brown’s script, like the reason the Wicked Witch removed the Scarecrow’s brain: something to do with her displeasure at his warning—he was a scientist—about a crop-damaging spell. These augmentations add little of importance.

The several numbers that are most familiar—like “Ease on Down the Road,” “Slide Some Oil to Me,” “Home,” and “Don’t Nobody Bring Me No Bad News”—can still shake the multitudes, especially the last named, performed by Melody A. Betts as Evillene, the Wicked Witch of the West. She delivers the goods as a gasket-busting, roof-rattling, vocal explosion, one thunderclap note topping the other. But it’s only the climax to a parade of voice-straining songs, turning the show into a belting competition. Whether singing, dancing, or acting, this company sometimes pushes the limits of energy expenditure, and it shows.

Schele Williams’s direction is spirited, but earthbound when it should be out-of-this-world imaginative. And her show is deprived of too many iconic markers. The yellow brick road, originally suggested by both a floor pattern and a team of dancers in yellow costumes, is now simply the latter, a serious loss. The chorus of Munchkins—played by dancers on their knees in 1975—is also gone (they’re now called “townspeople”), perhaps as a nod to political correctness. Nor do we meet the farmhands who later show up as Dorothy’s nonhuman friends. Perhaps the most obvious MIA victim is Dorothy’s pup, Toto, which kids will surely miss. As for script changes, there are too many to cite, among them the Wiz’s confession of how he came to Oz and got to be The Wiz.

JaQuel Knight’s lively choreography is not especially unusual; a highlight is the “Tornado” sequence, where several swirling dancers join a central one wearing flowing fabric. It lacks the impact of the even more exciting 1975 original, however, which focused on the main dancer, fabric streaming from hair and body, as others appeared with inside-out umbrellas and streamers on poles; the eye-catching human twister image apparently inspired the iconic album cover design.

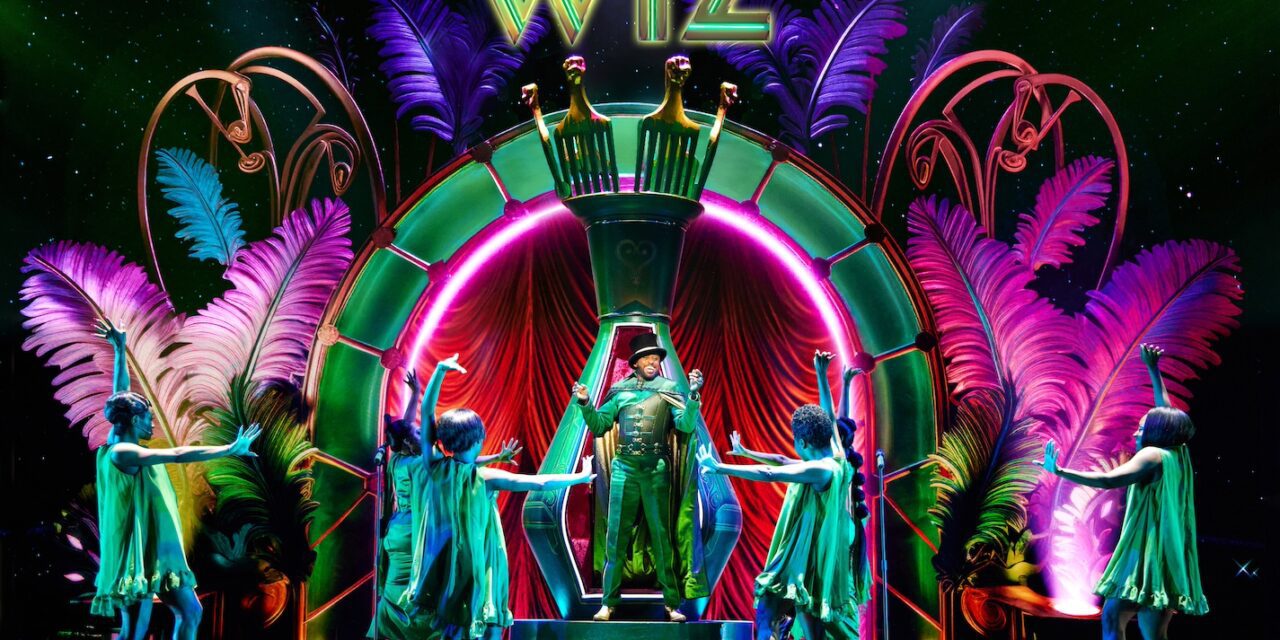

Hannah Beachler’s sets for the multi-scened show—framed within a triple border decorated with an African-inspired design—depend heavily on Ryan J. O’Gara’s lavish lighting and Daniel Brodie’s color-saturated videos and projections; this may be because the show is built for touring. The general aesthetic, though, is a catch-as-catch-can hodgepodge. Sharen Davis’s costumes also fail to break any ground in a show that should thrive on eye-popping surprises.

In 1975, 15-year-old Stephanie Mills became a star as the silver-slippered (yes, silver, not ruby) Dorothy, and it’s likely that 24-year-old Nichelle Lewis, who packs a huge voice in her slender frame and can also dance, will make her mark. Wayne Brady, who gets relatively little stage time, is a smooth, genial, emcee-like Wiz, nothing like the white-suited, pimp-like, epicene Wiz played in 1975 by André De Shields. Melody A. Betts is the biggest scene stealer as both Aunt Em and, memorably, Evillene. Deborah Cox gives us a physically and vocally glowing blonde Glinda. Kyle Ramar Freeman’s Lion is a bit too prissy for my taste; Phillip Johnson Richardson is a well-oiled Tinman; and Avery Wilson makes a blonde-thatched, athletic Scarecrow.

Mediocre as much of this two-hour-and-20-minute mounting is, it has its redeeming features. Much of the score is worth hearing, there are appealing, if not game-changing, performances, and the indelible charm of Baum’s fabulous story comes through despite the drawbacks. It’s a shame the cost of tickets is too high to encourage families of modest means to take their kids. As a TV ad for Crazy Eddie, a local, now defunct, electronics/appliance store used to scream, “These prices are INSANE!” By the way, Crazy Eddie’s chief competitor was Nobody Beats the Wiz.

The Wiz. Open run at the Marquis Theatre (210 West 46th Street, between Broadway and Eighth Avenue). www.wizmusical.com

Photos: Jeremy Daniel