Ziegfeld Follies

By Samuel L. Leiter

The Twinkling Twenties probably never twinkled more tantalizingly than when they focused their peepers on revues, both those with one-time-only titles, and those that returned annually with their titles differentiated only by the year. The Ziegfeld Follies of . . . , The Passing Show of . . . , The Greenwich Village Follies of . . . , The George White Scandals of . . . , and so forth. Now and then a year might be missed, but by and large these shows, evolving out of the vaudeville format that had reigned since the late 19th century when the word “variety” was more common, arrived each season like clockwork.

They offered sumptuous, plotless packages of female pulchritude, topflight comedy sketches, new songs, and strikingly attractive sets and costumes, only rarely offering the kind of thematic throughlines more common in present day revues.

Today’s installment of Leiter Looks Back reminisces about three of the more eminent efforts of the 1920-1921 season, The Ziegfeld Follies of 1920, The Greenwich Village Follies of 1920, and The Passing Show of 1921. If you wonder what’s gone missing, their titles are Cinderella on Broadway, Buzzin’ Around, Silks and Satins, Broadway Brevities of 1920, Biff! Bing! Bang!, Sunkist, Snapshots of 1921, and The Broadway Whirl.

Ziegfeld Follies

The crème de la crème of extravagant revues, of course, was the Ziegfeld Follies, around since 1907 and lasting until 1931. The 14th edition, which opened at the New Amsterdam Theatre on June 20, 1920, and piled up 123 performances, offered the usual glorification of the American girl, typically adorned in exquisite costumes (by Lucille and Madame Frances), often affording lavish glimpses of forbidden flesh. Accompanying them were top-flight singers, dancers, and comics, backed by Joseph Urban’s opulent settings, perfectly directed by British import Edward Royce, with overseen by the impeccable producer, Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr.

Ziegfeld Follies

This edition of a show now called “A National Institution,” most of its songs by Irving Berlin, was marked by the sparkling presence of toe-dancer Mary Eaton (replacing the previous dancing star, Marilyn Miller). Also aboard was the singing, dancing, and clowning genius Fannie Brice, singing new tunes such as “I’m an Indian,” “I’m a Vamp from East Broadway,” and “I Was a Floradora Baby.” Another fine contributor was the intelligently humorous Charles Winninger (who would one day create the role of Captain Andy in Show Boat).

Adding to the enjoyment was tenor John Steel, singing Berlin’s “Girls of My Dreams” and “Tell Me Little Gypsy”; misanthropic comedian W.C. Fields, who scored with zany comedienne Ray Dooley in Fields’s “Family Ford” sketch, with Dooley as a bratty juvenile; eccentric dancer Jack Donahue; the singing team of Gus Van and Joe Schenck; Venetian tableaux arranged by Ben-Ali Haggin for “The Love Boat,” a song by Victor Herbert; a melody by band leader Art Hickman, “Hold Me,” that became a hit; and finally, brought on late to tear down the house, all-around entertainer (and blackface specialist) Eddie Cantor. (When Cantor left the revue, he was replaced by blackface comics Moran and Mack.)

Production numbers included “Leg of Nations,” presenting a display of shapely gams; and “Bells,” in which bells on the chorines’ costumes tinkled cleverly in tune with the music.

The Greenwich Village Follies

If Broadway excess, including the biggest stars, marked shows like the Ziegfeld Follies, intimacy and charm (musical, comical, and visual), albeit with lesser-known performers and creatives, were hallmarks of The Greenwich Village Follies. The series was created in 1919 by director-producer John Murray Anderson, Off Broadway at the Greenwich Village Theatre. The second edition opened there on August 30, and soon transferred to Broadway’s Shubert Theatre, eventually running for 217 performances.

It was memorable on several accounts, but the critics dwelt principally on its visual delights, with dazzling costumes by Robert Locher and marvelous sets by James Reynolds, a major discovery of Anderson’s soon snapped up by Flo Ziegfeld.

“It is a shimmering thing of silks and satins, of gold cloths and silver cloths, of soft drapes and splashing color effects, of costumes surely as stunning as ever have graced the revue stage,” noted the Times. The Evening Telegram said the sets were reminiscent of those created by Gordon Craig and Leon Bakst.

Many of the routines went over well, among them “Song of the Samovar,” a number that employed a procession dressed in medieval Russian costumes and climaxing in a sensational dance by Ivan Bankoff and Mlle. Phebe. One number, “Tam, Tam, Tam,” introduced audience participation by passing out tiny tambourines so everyone could bang on them instead of clapping.

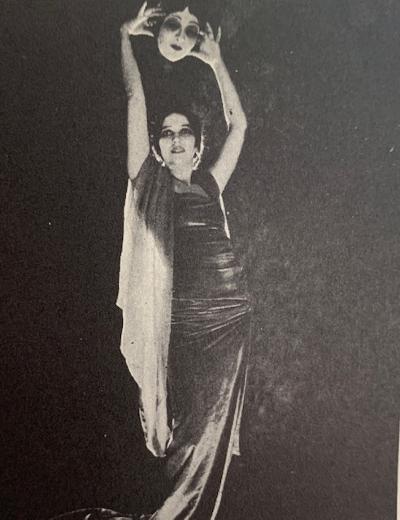

The masks of Benda made a startling impression as employed by interpretive dancer Margaret Severn in the Empire-styled “The Golden Carnival,” in which she transformed from one character to another. Comedy was entrusted to the teams of Meyers and Hanford, Collins and Hart, and, most successfully, Bert Savoy (a top female impersonator) and Jay Brennan. Frank Crummit, ukulele-playing singer/comedian, traipsed through the exhibition as the M.C., and also sang such songs as “Just Snap Your Fingers at Care” and “I’m a Lonesome Little Raindrop.”

Nudity played a role, especially in the opening number, “The Naked Truth,” set among a crowd of artists and models, with a team of showgirls gathering to form the image of Miss Greenwich Village. Other popular numbers (music by A. Baldwin Sloane; lyrics by John Murray Anderson and Arthur Swanstrom) were “Just Sweet Sixteen,” with chorines dressed as cake and candles; “Come to Bohemia,” which ribbed a local dive; “I’ll Be Your Valentine,” replete with romantic symbols of February 14, played to a song that gained hit status; Savoy and Brennan in “Come to Bohemia,” set in a louche dive, with Savoy costumed as Lady Nicotine and Brennan got up like an apache; “The Krazy Kat’s Ball,” based on the popular comic strip; and a perfume allegory, “Tsin,” performed around a reflector pool, with a bevy of beauties masquerading as various bottled fragrances to the accompaniment of Rimsky-Korsakoff’s “Scheherazade.” It also offered Margaret Severn a chance to slither through a scintillating Oriental dance.

The Passing Show

The Passing Show series, created by the Shubert brothers to rival Ziegfeld’s extravaganzas, used the Winter Garden as its venue since its 1912 inauguration. The 1921 version (there was none in 1920), the series’ ninth, opened on December 29, 1920, and scored 191 performances, with a score by Jean Schwartz, supplemented by songs from Al Goodman and Lew Pollock. The opening performance featured such major entertainers as comics Eugene and Willie Howard, Marie Dressler, and Harry Watson, but a number of cast changes followed during the run.

As per many typical revue sketches, takeoffs of popular shows were among the funniest things on view, with spoofs taking aim at such 1920-1921 hits as Mecca, Spanish Love, Lightnin’, The Bat, and The Charm School. In other pieces, beautiful showgirls, sexily dressed, paraded about on a runway connecting the orchestra to the stage. One notable number was “Dream Fantasies,” featuring Cleveland Bronner and Irene Solfeng in a ballet sequence using swirling muslin drapery—à la Loïe Fuller—to create stunning images of moths, flames, fireflies, spirits, and the like. A parody of Rigoletto had spectators in stitches, especially when Willie Howard kept peering down the soprano’s cleavage as she strained for high C.

Not a few critics considered this best of the series to date. “This year,” said Arthur Hopkins, “the girls seem to be less beefy, more graceful, lithe and sprightly than ever before.”