by Myra Chanin

Sometimes in the world of theater reviews we stumble across the good fortune of having pieces by two different esteemed critics, allowing us to see comparative and contrasting viewpoints—always an intriguing experience. This is one such time and, if nothing else, the two pieces underscore the delights of Zero Hour. Here’s our review from Myra Chanin. For a review by Samuel L. Leiter, please click here. – Ed.

by Myra Chanin

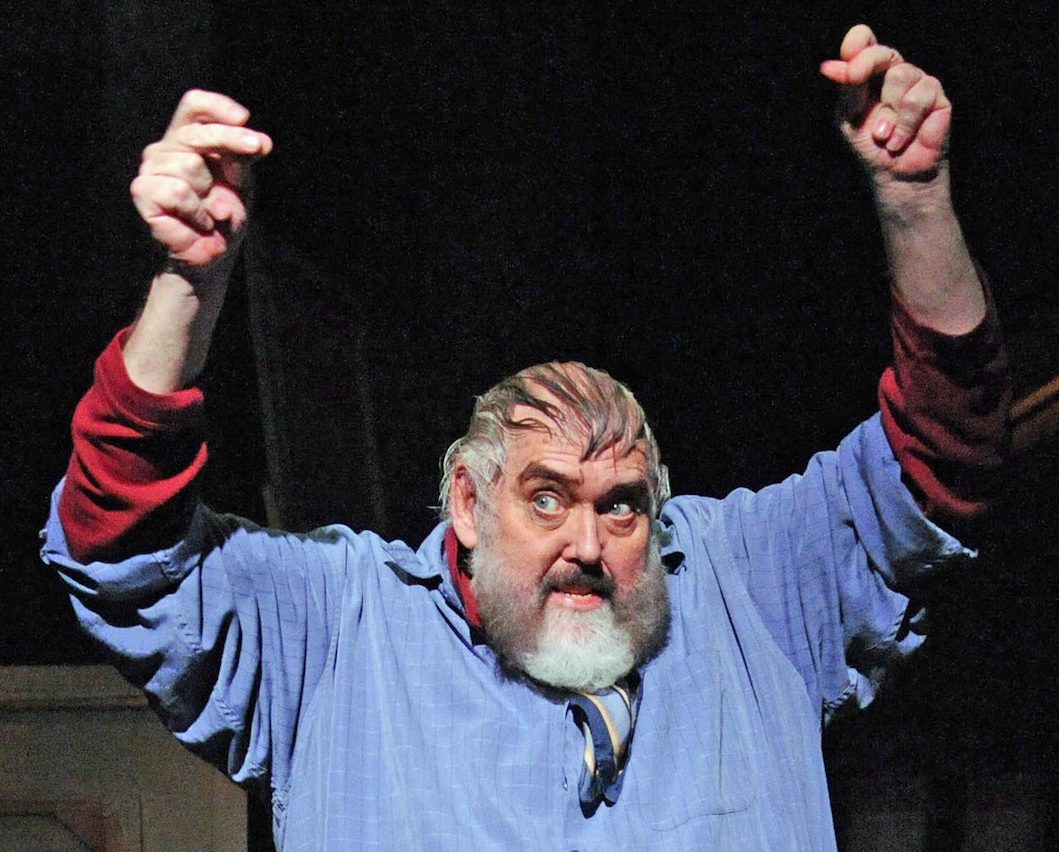

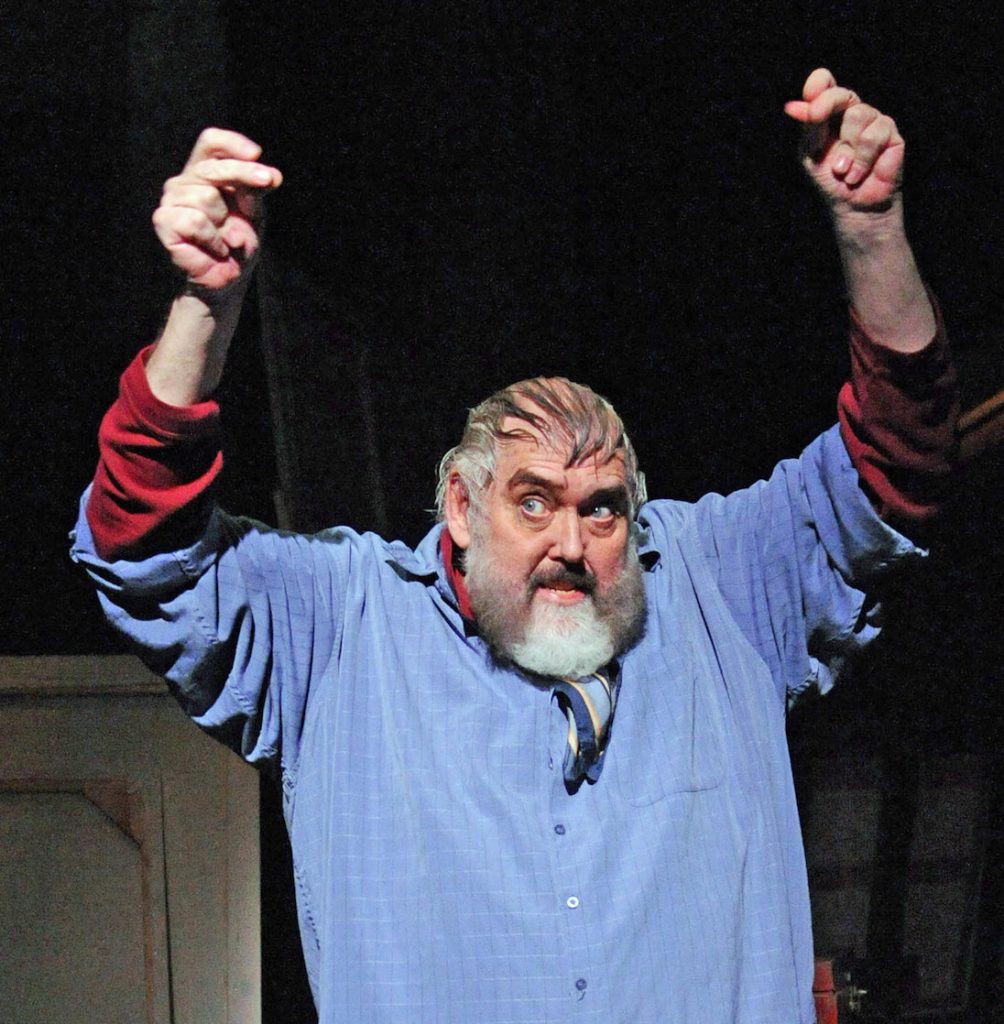

Zero Hour is not only the absolutely best solo performance I’ve ever seen in my life, it’s actually 90 minutes when the-no-slouch-himself-at-winning-awards creative spirit, playwright/actor Jim Brochu brings Zero Mostel of Blessed Memory miraculously back to life, not only in his considerable flesh and with a perfect comb-over noch, but in his complete, complex, indomitable, inventive, imaginative, generous, bullying spirit.

Zero Mostel was the complete creative artist: a serious painter, an incomparable clown, a stand-up comic with perfect timing, and a mimic who transformed himself into objects with the aid of only his plastic face and supple body. Mostel was also an extraordinary actor capable of playing many parts (until he got bored with repetition and began improvising) from Plautus, Shevlove’s and Gelbart’s Pseudolus; Bertold Brecht’s Shu Fu, Mel Brooks’ Max Bialystock; Duke Ellington and John Latouche’s Hamilton Peachum; Arnold Wesker’s Shylock; Samuel Beckett’s’ Estragon; Ionesco’s Rhinoceros and Sholem Aleichim’s Tevye the Dairyman. As for Mostel’s Obie Award-winning performance as James Joyce’s Leopold Bloom, Newsweek’s critic declared, “A fat comedian named Zero Mostel gave a performance that was even more astonishing than Olivier’s!” That’s Laurence Olivier, folks! And that ain’t chopped liver.

Zero Hour takes place in Zero Mostel’s West 28th Street painting studio in 1977. Arthur, a naïve New York Times reporter, arrives to interview the famously volatile star right before Mostel will be leaving for Philadelphia for out-of-town tryouts of new play with a kinder view of Shylock based on the same tales that inspired Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. Arthur, who is neither seen nor heard, may utter “Zero Mostel?” before Zero Hour begins. That phrase prompts an explosion of memory, humor, outrage, and backstage lore which include Zero’s theatrical triumphs (his fulfilling marriage and testifying and outwitting the HUAC by not naming any names and resolving his love-hate relationship with director Jerome Robbins) along with his sorrows (the traffic accident that almost ended his career, being blacklisted and out of work for 10 years, and his lengthy estrangement from his unforgiving mother because he married a non-Jew). Jim Brochu, who penned this peerless appreciation for the many sides of Zero, kindly gives the reporter the last word—a punch-line that’s smart and skillful enough to make Zero spin in his grave with jealousy. Zero Hour proves once and for all time that if an actor wants to find an ideal script for himself, he’d better simply write it himself.

Samuel Joel Mostel began his creative life as a visual artist and continued drawing and painting all of his life, but his duality of character was always present. Alone he was thoughtful, studious and quiet, but if there were people around him, he used comedy to make himself the center of attention. Despite claims that he was named Zero after his school grades, he was actually an A student. His high school yearbook prediction? “A future Rembrandt . . . or perhaps a comedian.”

Zero studied art at CCNY and after graduation gave gallery talks at Manhattan museums where audiences not only encouraged his humorous comments, but hired him at $3-5 per gig to entertain at private parties. By 1941 he was a regular at Café Society, where stars like Billie Holliday headlined. Within months Zero was the headliner Café Society at a salary of $450 per week. In 1943 Life Magazine declared him “just about the funniest American living.” For more complete delicious and demeaning details, see this absolutely delightful show.

What Zero Hour? Those 90 minutes were the 100% most enjoyable hour and a half I’ve spent in years. Jim Brochu deserves a double A+ for impeccable playwriting and a flawless performance. Director Piper Laurie rates several Hip, Hip, Hip, Hurrahs for her discrete direction and for impeccably maintaining the ideal balance between Mostel/Brochu’s chutzpah and anguish. Eliminating the unnecessary intermission break and cutting 20 minutes from an earlier version of Zero Hour supplies the present version with an incredible emotional wallop.

The performance I attended had almost no audience members younger than 35. That’s criminal! Mostel has great appeal for young people. He’s outrageously non-conformist. And sooo funny! Take your grandchildren to see Zero Hour and they will repay you by visiting you every week when your children send you off to “The Home.”

I, who never see anything twice, plan to see Zero Hour again. I loved every second of it—another miracle coming from a kvetch that was raised to focus on flaws by her mother.

Zero Hour will be performed until July 9 at The Theatre At St. Clements with fascinating post-Sunday matinee talkbacks.

Sunday, June 18: “Meet The Artist Who Plays The Artist” — Jim Brochu explains to moderator Robert W. Schneider of the “Behind the Curtain” podcast why he was inspired to write about Mostel.

Sunday June 25: “Memories of Fiddler” — Fiddler original cast member Austin Pendleton reveals what working with Mostel was like to moderator Jim Brochu.

Sunday July 9: “Memories of Zero, Forum and Fiddler” — Twenty-one-time Tony Award winner Harold Prince who produced Fiddler on the Roof and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum shares his experiences with Mostel with moderator Kurt Peterson.

Zero Hour. Through July 9 at Theatre at St. Clements (423 West 46th Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues). www.thepeccadillo.com

Photos: Stan Barouh