By Samuel L. Leiter

I was only five in 1945, but even then I was aware of five major events in that earthshaking year: the death of FDR, the atom bombs, the end of the war, my introduction to Broadway, and, finally, the crowning of Bess Myerson as the first (and, still, only) Jewish Miss America.

To my Jewish family in Brooklyn—secular as we were—recognition of Bronx-raised Myerson’s beauty, charm, and musical talent was a blazing skyrocket of affirmation and assimilation in a world darkened by the recent Holocaust.

It’s only natural that I and many others who grew up in the following years, when Myerson became a popular figure, might be intrigued by Miss America’s Ugly Daughter, a biodrama at the Marjorie S. Deane Little Theatre, written by and starring her own daughter, Barra Grant. Even though Myerson may no longer be widely remembered (my middle-aged plus-one was only barely aware of her), the play ran for a year in Los Angeles before receiving its New York premiere, directed by Eve Brandstein.

Miss America’s Ugly Daughter is a variation on the conventional one-person play, since what would otherwise be an 85-minute is monologue constantly interrupted by the offstage voice of an actress playing Myerson (understudy Margaret Reed, filling in for Anna Holbrook when I went). These interruptions arrive via late night calls from an anxiety-ridden Myerson to her irritated daughter, who must contend with her mom’s persistent but innocuous concerns while struggling to find her own identity. “This is not about you,” she reminds Queen Bess.

Barra Grant, 71, offers a deeply personalized account of what she endured as the offspring of a famed beauty who also gained respect for her political work (she was New York Commissioner for Consumer Affairs, ran for the Senate, and held many notable appointments) and activism, especially on behalf of Israel-related causes.

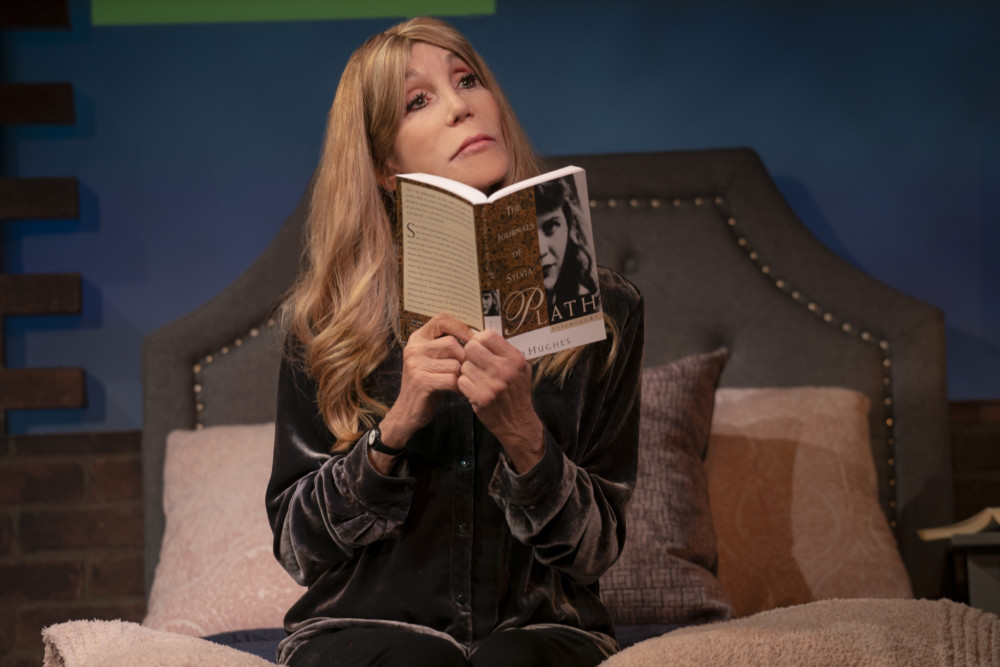

Grant, although burdened by being nowhere as striking as her mother, was certainly not the meeskite her self-deprecatory title suggests. I’ll let the accompanying photos cover her appearance. Seriously bookish—she mentions intellectual downers like Tolstoy, Nietzsche, Kafka, and Plath—she matured into a professional actress, screenwriter, and TV producer.

It’s easy to imagine that the personable, intelligent, and telegenic Myerson led a dazzling existence, admired not only by the populace but by many powerful men (including Ed Koch, referred to as “a feygele”), but her life had rough edges, often because of her romantic choices and broken marriages, but also because she was an insecure narcissist. Grant, chubby and unprepossessing in youth, had to endure her mother’s perfectionism regarding her own looks and behavior.

Grant shares many stories of Myerson’s eccentricities, some of which are similar to those associated with traditional images of depressed Jewish mothers, such as her constantly threatening to kill herself. She was also both a cheapskate and a schnorrer, taking salt and sugar packets at restaurants, toilet paper from public bathrooms, and airplane blankets to give as gifts. Infamously, she once got nabbed for shoplifting.

Myerson’s later career was marked by scandal, most outrageously in the 80s as a result of her affair with Andy Capasso, a Mafia gangster, decades younger. Grant’s play seems to be building toward this story, the notorious “Bess Mess,” but, when it arrives, it’s dispensed with too quickly and becomes almost anticlimactic.

Given that this is essentially a dual biodrama, there’s probably too much here to unpack—some of it laugh-worthy, much of it not. It’s hard to turn away from gossip, though, when it’s from the next best thing to the horse’s mouth.

Grant, dressed by Florence Kemper Bunzel in black slacks and a black, velvet tunic, moves a bit stiffly around Elisha Schaeffer’s set of a desk, a throne-like chair, and a bed, backed by multiple images projected on the rear wall. These, presumably, are part of Yael Lubetzky’s lighting design (which once or twice shadows the star’s face). Tom Jones’s interpolations of period music (accompanied by dance moves) help push the chronology forward.

Grant is a pleasant, undemonstrative performer with a husky voice that—based on her use of a prop bottle—suggests at least some lasting effect from the contents of such things. While not given to histrionics, she earns our engagement as she slowly leads to what, after all, is intended as an act of forgiveness.

Miss America’s Ugly Daughter is neither a mess nor the best of Bess but the inherent fascination of its subject covers a multitude of sins.

Photos: Joan Marcus

Marjorie S. Deane Little Theater 10 W. 64th St., NYC Through March 1