by Carole Di Tosti . . .

The Irish Repertory Theatre’s searing presentation of A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing in the W. Scott McLucas Studio Theatre is difficult to experience. Adapted by Annie Ryan into a solo show from Eimear McBride’s award-winning novel, the character of “The Girl,” portrayed by Jenn Murray takes the audience through the highs and lows of what it means to be a young teenager who is emotionally and psychically abused by her mother and sexually abused by her uncle.

Ryan’s adaptation reveals the victimization of young girls by older men and how it impacts them in their future relationships with other men. To add power to Murray’s performance, the set is minimalistic dark grey black with occasional lights rising on sections of the backdrop. That’s all that is needed to reveal The Girl’s mental state as she relays her life experiences with her brother.

Murray’s performance is stark, painfully rendered and, at times, incoherent in keeping with the characterization set forth by McBride. Directed by Nicola Murphy whose depth of understanding ably shepherds Murray through her devastating performance, we acknowledge the key themes of the adaptation and beyond in McBride’s novel.

Young girls who should be nurtured and treasured are treated as throwaways, especially in paternalistic cultures (this takes place in Ireland) that have religion as their moral lifeblood. They are belittled by their own mothers, who, most probably, have been verbally and physically abused. Likewise, the men in the family instinctively know that these young girls, who have been broken down, can be manipulated and used with impunity, acting out on them their own inner torment. This is a tortured, cyclical familial abuse that is most probably generational.

Through broken phrases of description and dialogue The Girl chronicles snatches of her life with her abusive mother and her brother who nearly died but recovers, after an operation that leaves him with a large visible scar. She is close to her brother and when their mother decides to sell the house, upend their lives and move away, it is an adjustment for her and her brother with their new schoolmates. They make fun of her brother who is debilitated, and they scorn him for the large scar on his forehead that he cannot cover up.

With chopped language carried by emotion, The Girl discusses how she is sexually abused at 13 years-old by her uncle. The act dislocates her sense of identity, confidence and wholeness. Thrown off course, she both desires the attention he gives her, yet understands that it is wanton and vile. In the conflict that his sexual predation creates, she takes it out on herself and others. Thus, she seeks out other sexual acts with teenage boys as a punishment of herself and of them because she couldn’t fight off her uncle’s rape.

When the teenage boys make fun of her brother, she retaliates with physical intimacies proving that they are incapable of being “real men,” like her uncle. Of course, her behavior in weaponizing her own body to abuse the teenage boys is dissociative. In seeking apparent “pleasure” she creates emotional and psychic pain for herself and for the teenage boys. However, the only good that comes out of it is that they leave her brother alone, themselves feeling inferior, weak and unmanly.

Murray unravels the positive aspects of The Girl when she succeeds in getting into college, has friends and doesn’t pursue a wanton approach toward men. But when her brother is sick and dying and she returns home, the situation reverts back to what it was when she was a teenager. The emotional pain she endures is horrific; her uncle attempts to rekindle the sexual experience they had when she was a teenager. And once more, she is led to punish herself by seeking out sexual acts with men who are strangers in what becomes a gruesome, visceral and self-demoralizing act. After her brother dies, she repeats the cycle begging a stranger she encounters in a field to physically abuse her.

Murray’s performance is graphically rendered, powerful and upsetting. We understand that The Girl cannot cope with the loss of the only person in the world she loved. Thus, like those who are “Cutters” (the individuals cut their flesh to release the psychic pain they feel) she seeks out physical and sexual abuse to release the agony of now being alone in the world without anyone to receive her love. It is clear that The Girl’s mother would never believe that her own brother abused her child; nor would she take her for help; nor would she press charges against him. All is kept quiet and hushed up and The Girl, left to her own devices, helplessly turns her inner emotional pain against herself seeking physical torture.

There are no names given; only the blood relationships to The Girl are stated. This allows us to more easily identify with our own families and stand in The Girl’s shoes.

Murray and Nicola Murphy have created in this one woman show an incredible tour de force that I found unnerving. Precisely because The Girl is a victim, who then turns her own self-loathing inward, and is never able to get out from under her guilt and self-annihilation, the audience is cast in the position of victim. We want to scream out: “Stop hurting yourself;” “Press charges against your uncle;” “Tell your mother!” However, like The Girl, we realize that at that time and in that culture, the ability to resist and strike back was heavily punished or ignored. Instead, The Girl was made to feel the “insane” and “sick one,” a half-truth for a “half-formed thing.”

A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing takes an unflinching look at abusive culture and how it is carried on by families. Kudos to the creative team: Chen-Wei Liao (set design) Esther Arroyo (costume design) Michael O’Connor (lighting design) Nathanael Brown (original music & sound design).

Irish Rep (132 West 22 St., NYC) thru Dec. 12 www.IrishRep.org Tickets: HERE

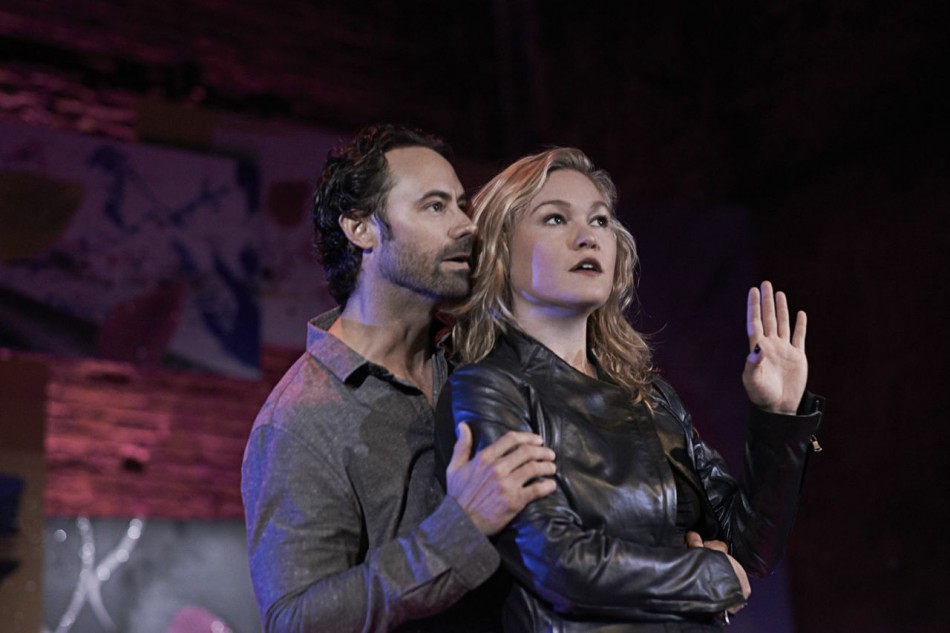

Photo: Joan Marcus