By Carol Rocamora . . .

“F***ing business!”

Who better than David Mamet can sum up the essence of American society and its values in only two words and make them sound so eloquent!? As articulated at the end of Act I in American Buffalo, now playing at Circle in the Square in a smashing new revival, they bring down the house with a bang—one that confirms the play’s status as an American classic.

David Mamet—moralist, master of macho-speak—has been writing about our society’s ills for decades. American Buffalo (1975) was followed by Glengarry Glen Ross (1983) about the corruption and brutality in the real estate industry. Speed-the Plow (1988) satirized the wheelings-and-dealings of the dog-eat-dog movie industry. Business, Hollywood, American academe—no aspect of American society escapes Mamet’s satiric gaze and his determination to expose all that is corrupt, inhuman, and destructive.

So this powerful revival of American Buffalo is an opportunity to celebrate Mamet’s contribution to American theater and film. This early play contains the seminal themes that Mamet has developed in over three dozen plays and two dozen films during his fifty-year career. It also showcases that signature minimalist Mamet style—born of Pinter and Beckett—that has influenced so many writers after him.

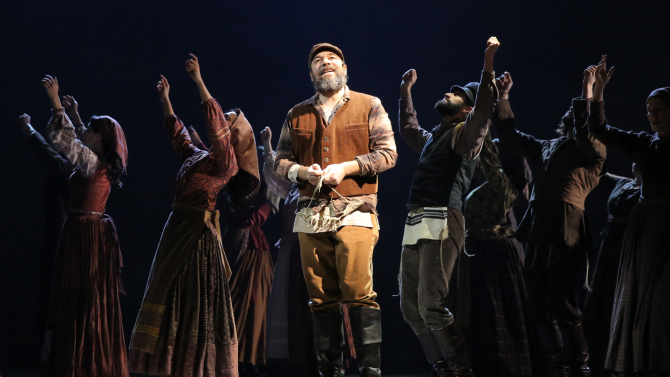

This dynamite revival, set in a junk shop owned by Don (Laurence Fishburne) over a twelve-hour period, features three small-time Chicago crooks trying—and failing—to pull off a burglary. Don has just sold a buffalo nickel to a customer for $90 but is now suspicious that it is worth far more. He hatches a scheme to steal it back from the customer with the aid of his assistant, the clueless Bobby (Darren Criss). But the high-wired Teach (Sam Rockwell), a buddy of Don’s from his poker game, wants “in” on the plan.

That’s the plot, essentially. Act I features the interaction between these partners-in-petty-crime who become the quintessential gang that can’t shoot straight. There is an intense, heated discussion over who else should be involved in this proposed burglary—namely, Fletcher, another poker-playing buddy. There is aargument over how much the nickel is really worth. There’s confusion as to whether Bobby did or did not see the purchaser of the nickel leaving his house with a suitcase. There is disagreement as to who should do what. In short, we watch these bunglers posturing, competing, lying, vying and tying each other in knots.

In Act II, the atmosphere abruptly turns darker as the tension escalates. Bobby appears at the store just before midnight—the appointed time for the robbery—with a buffalo nickel that he now wants to sell to Don. (Where did he get it?) More confusion ensues when Bobby tells Don that Fletcher is in the hospital, but isn’t sure which one. The frustration level crescendos until a sudden, shocking act of violence is committed (no spoiler).

The production shines on numerous levels. Designer Scott Pask’s junk shop is a work of art—an overwhelming profusion of furniture pieces, record players, bird cages, dolls, hockey sticks, mismatched china, and candlesticks, overhung by dozens of chandeliers (lit by Tyler Micoleau). It’s a masterpiece of confusion, reflecting the state of mind of the characters who inhabit it as well as the confusion of American values based on “stuff”—namely, materialism.

In American Buffalo’s fifty years of life on the stage, many great actors have played its plum roles, including Bill Macy (1975 and 2000); Robert Duvall (1977); Al Pacino (1983); not to mention John Goodman, Damian Lewis, and Tom Sturridge (2015) in London. Of all the productions I’ve seen over the years, the current cast achieves a new level of brilliant ensemble playing. As Don, the ringleader, Laurence Fishburne gives a commanding performance; as Teach, Sam Rockwell is both dangerous, unpredictable, and at the same time laughable; as Bobby, Darren Criss exudes a touching vulnerability. Together, under Neil Pepe’s inspired direction, they make theater magic, creating a unique combination of entertainment and edge-of-your-seat tension.

Ultimately, Pepe’s splendid production provides a new insight into American Buffalo—as a play more about friendship than about American business (you’ll see, in the ending I dare not reveal). Under Mamet’s tough iconoclastic exterior, there’s heart and humanity that ultimately triumphs at Circle in the Square. Moreover, this is the funniest version of American Buffalo I’ve seen. This can be credited to Neil Pepe’s long association with David Mamet (they were co-founders of Atlantic Theater Company) and Pepe’s deep and maturing understanding of Mamet’s work. Pepe’s swift, exacting direction highlights the terseness, toughness and precision of Mamet’s dialogue—and the results are often absurd. “The thing,” for example—as the co-conspirators call their planned robbery—becomes a laugh line every time it is mentioned, because of its inarticulate ambiguity.

Who knew that tough-talking David Mamet could be so funny and, ultimately, so moving? One “thing” we know about Mamet’s provocative writing, however, is that its deep insights are enduring. Seeing this play today, we ask: are American business ethics becoming as extinct as the American buffalo itself?

American Buffalo. Through July 10 at the Circle in the Square Theatre (235 West 50th Street, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues). www.americanbuffalonyc.com

Photos: Richard Termine