Review by Carol Rocamora . . .

“Attention, attention must finally be paid to such a man!”

That cry from Linda Loman, wife of Willy, has rung out on our stages ever since Arthur Miller wrote it in his immortal American tragedy, Death of a Salesman, in 1949. Since then, we’ve heard it said of a legion of great American actors who have played the role over the decades – from Lee J. Cobb, George C. Scott, Dustin Hoffman, Brian Dennehy, to Philip Seymour Hoffman.

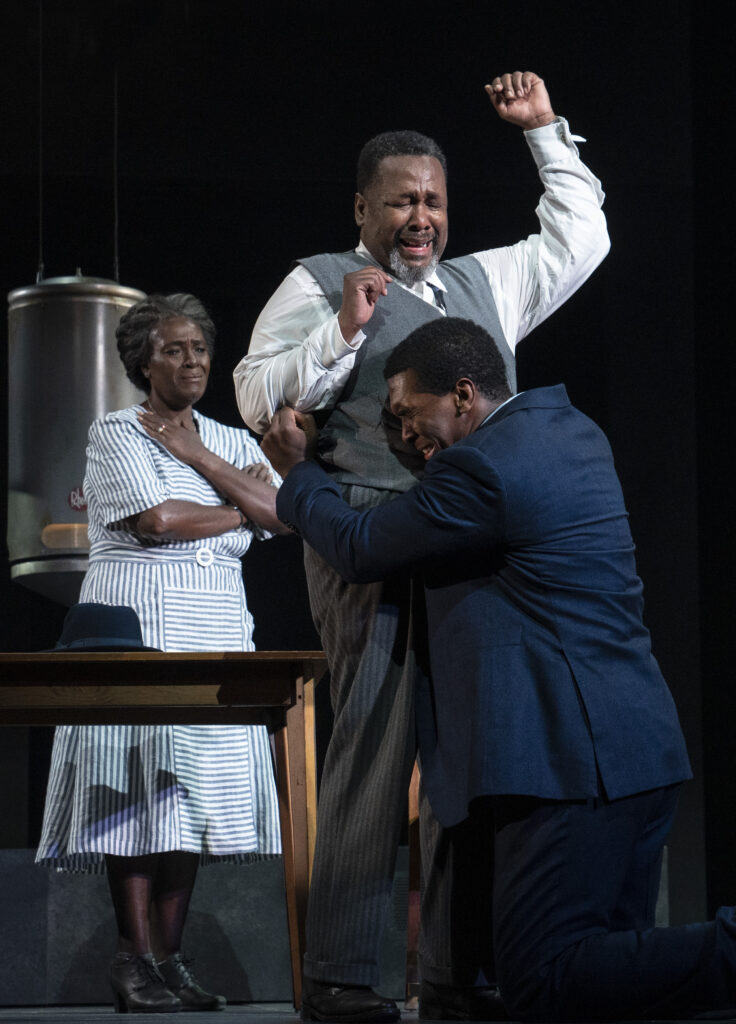

But when that cry comes from a voice as deep and compelling as Sharon D. Clarke’s, in the devastating revival that just opened on Broadway, that’s when we all rise up and pay attention anew. It’s a cry from a Linda of uncommon strength and conviction – directed at Wendell Pierce, one of the most vulnerable Willys ever to walk the stage.

Such is the power of Miranda Cromwell’s current production, that originated at London’s Young Vic Theatre in 2019 and transferred to the West End’s Piccadilly Theatre, co-directed by Marianne Elliott and Cromwell.

Death of a Salesman, Miller’s American tragedy of the common man (as he called it in his famous essay) has been incorporated into our culture as the greatest classic of the 20th century, taught throughout the land in secondary schools with reverence. This well-known story – of a little man at the end of a failed career as a road salesman, unable to achieve the (hollow) American Dream, suffering the ultimate humiliations of defeat, leaving no legacy for his family but “a smile and a shoeshine” – has been performed around the world. (Miller himself directed it in China with a Chinese cast).

So what gives this current revival its special power, its great magnitude, its new command for attention?

For starters, Elliott and Cromwell have cast the Loman family with a group of outstanding Black actors, broadening the play’s scope and universality. Thus, many moments in the play acquire a new intensity. The scene, for example where Willy is fired from the firm he served for decades – by a young (white) man whom he named Howard at birth (Blake DeLong) – is all the more humiliating. So is his affair with a white secretary (Lynn Hawley) while he’s “on the road”, who ultimately dismisses him as well. So is the scene where the bereft Willy refuses to accept a job from Charley (an affecting Delaney Williams), his best and only friend (who is white).

But for me, the power of the performances transcends the sociological/racial implications. The utter pathos of Wendell Pierce’s Willy evokes the requisite elements of “pity and fear” that Aristotle calls the essence of tragedy. We care about his Willy desperately, we fear for him, we cringe as he bends down to pick up an item that Howard (his “boss”, half his age) has dropped. I heard other audience members cry out when Willy extends his hand to Howard (after having been fired), and is rebuffed.

As his older son, Biff, Khris Davis gives an achingly heartfelt performance of a young man who is stuck in the wrong dream – the American one of success in business – that his father so desperately wants for him, in order to compensate for his own failure. Ultimately, Biff can only begin to realize his own dream (to work outdoors with his hands) by rejecting his deluded father and his “fake dream.” As his younger brother Happy, McKinley Belcher III, a philanderer and a compulsive liar, is nonetheless both pitiable and endearing in his determination to make his father proud (though it’s doubtful he’ll ever achieve anything but being “the assistant to the assistant buyer”).

But the revelation of the play’s unplumbed depths comes from Sharon D. Clarke’s performance as Linda. From whence comes her strength, her conviction, and her endurance that has propped up Willy and kept the family together? It’s as if Ms. Clarke is channeling the fortitude of Lena Younger, the powerful matriarch of A Raisin in the Sun, another revival of an American family in search of The Dream, that will grace the Public Theater’s stage this month).

As the fifth Loman family member – the ghost of Willy’s older brother Ben, an adventurer and a financial success – Andre de Shields gives a surreal performance that haunts Willy throughout the play, reminding him of his missed opportunities, deepening his sense of failure and shame.

Miranda Cromwell’s imaginative direction and non-realistic touches support Miller’s vision, as articulated in the working title of the play, “The Inside of His Head.” As you know, the play takes place in the final 24 hours of Willy’s life (no spoiler, it’s a classic), when – exhausted from a failed career, fired by his boss, heartbroken by his sons – Willy’s hold on reality grows more and more tenuous. As Willy recalls a past filled with deluded hope, his son Biff (once a high school football hero) appears in uniform. Biff’s movements are stylized, and he’s directed to “freeze” as if snapshots from memory are keeping Willy’s hopes alive. These directorial touches, plus the non-realistic set by Anna Fleischle featuring a house with floating furniture to emphasize its emptiness, deepen the heartbreak of a family’s demise from the American Dream. An ensemble scene in the restaurant where Willy meets his sons for dinner – and faces the ultimate disappointment of Biff’s failure – adds to the atmosphere of teetering hope that will ultimately be dashed. The original music (Femi Temowo) – played by a guitarist who wanders in and out of the scenes – adds a rich, deep dimension, as do the spirituals sung at the play’s opening and close.

“The man never knew who he was,” eulogizes Charlie in the final scene, giving voice to the tragic figures who have haunted the theatre from Oedipus to Hamlet to Willy Loman today.

Death of a Salesman, by Arthur Miller, directed by Miranda Crowell, now playing at the Hudson Theater on Broadway (141 West 44 St. NYC) Run Time 3 hrs. 10 min. (one intermission)

Photos: Joan Marcus

Featured Image: Wendell Pierce, Sharon D. Clarke