by Harry Haun

The stars were out yesterday afternoon at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre —along with a couple of original cast members, a knighted Beatle, some revival headliners and at least one original conductor—to sing the praises of Jerry Herman, one of the few composer-lyricists to survive David Merrick twice (Hello, Dolly!, Mack & Mabel) and live for 27 years on the antiretrovial therapy (ART), commonly called the “AIDS cocktail.”

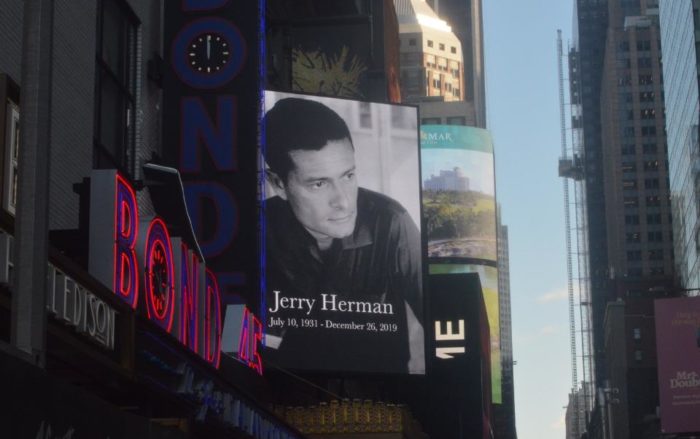

He died of pulmonary complications in Miami the day after Christmas at the age of 88–“the same number of keys on a piano,” his goddaughter Jane Dorian poetically pointed out to the gathering. When fellow composer Jule Styne died at the same age, his widow famously explained, “He just ran out of keys,” and the same might be said for Herman, who, at three, heard “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” on the radio and instinctively started playing it on the piano.

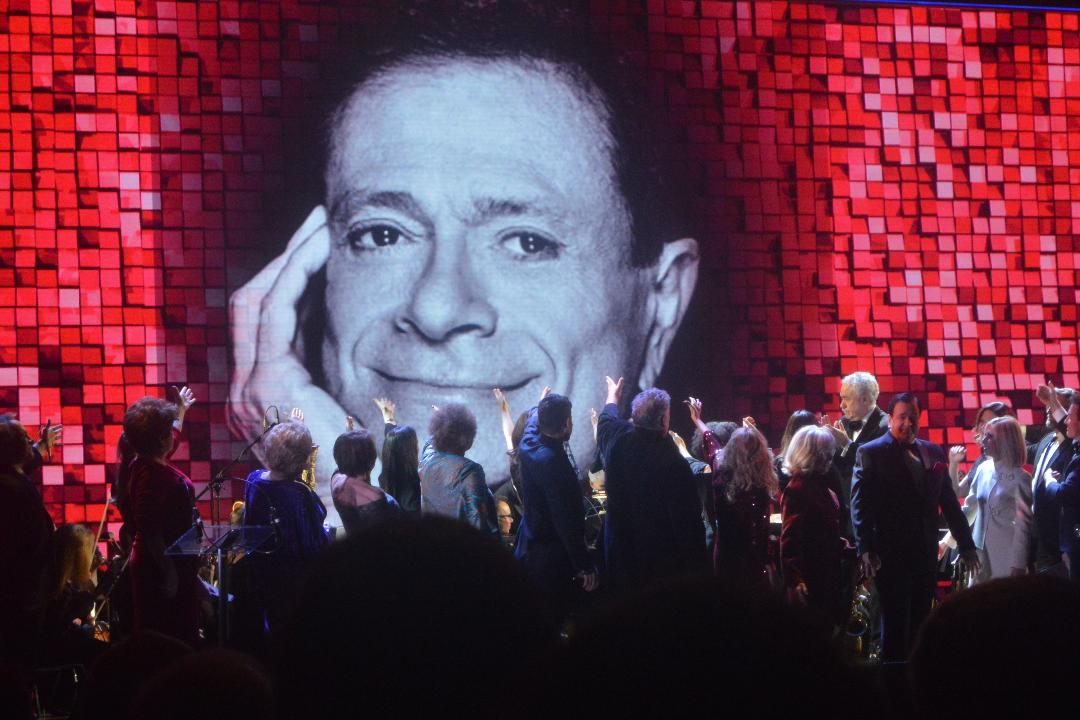

The SRO memorial at Lunt-Fontanne for him was by invitation only, but the mezzanine was turned over to his fans. On all levels, the place was packed to capacity with devotees of the kind of exuberant, feel-good music that the songwriter put out. Sixteen of cases-in-point comprised the program, delivered with solid Broadway know-how and punctuated periodically by speakers.

The music spoke for itself—volumes!—and made this memorial a celebration. Conductor Larry Blank managed The Big Sound of a 29-piece orchestra, augmented (when needed) by a choral backup 20 strong.

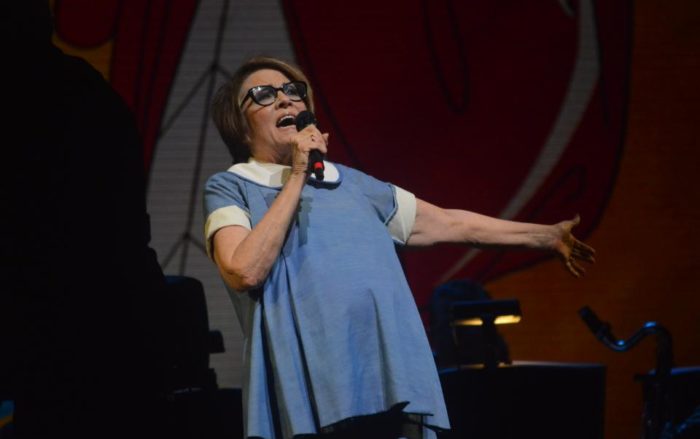

Marilyn Maye set the jubilant tone in the opening number, “It’s Today,” a title and song idea Herman got from his mother at an early age. He walked into her kitchen one day and found her baking a cake. “What’s the occasion? Who’s birthday is it?” he asked. “Nobody’s birthday,” she answered. “It’s Today.”

Heartfelt ballads were neatly laced between lighter fare. “I Don’t Want To Know” from Sutton Foster followed Jeremy Jordan’s “It Only Takes a Moment.” Lorna Luft did “Gooch’s Song” (a lament for living) in grand comedic style and a bulging maternity dress. Michael Feinstein, minus a piano, ached with the heartbreak of “I Won’t Send Roses.” Tyne Daly and Klea Blackhurst made a scrappy, snappy pair of “Bosom Buddies.” Kristin Chenoweth seemed a tad young to wear a mature Mame song (“If He Walked Into My Life”), as did Kelli O’Hara with a Dolly number (“Before the Parade Passes By”), but both equipped themselves well. Debbie Gravitte gave “Wherever He Ain’t” a robust accounting. Strong-lunged Ron Raines boomed out the title tune from Mame, and Betty Buckley, back from touring in Hello, Dolly!, strutted out her title tune; her Horace Vandergelder, Lewis J. Stadlen, was to have done his “It Takes a Woman” but was replaced by somebody called “the real John Bolton.”

Angela Lansbury, who won Tonys for his long-running Mame and all 132 performances of Dear World, appeared on film and spoke of the thrill of walking in Jerry Herman’s apartment and meeting him for the first time. Talk about a life-changer! “It is he who is responsible for giving me the role of Mame,” she declared definitively. “It was through him that I began my career as a Broadway actress, and my friendship with him goes back many, many years. I knew him. I knew his cat. I knew everything about his life at that time, and he was a thrilling person to be in love with. I’ll never forget him, and I will miss him for the rest of my days. Bless his heart. He was a wonderful, wonderful person and a great, great friend.”

Herman’s lavish townhouse on East 61st Street was also remembered by the book writer for Herman’s La Cage aux Folles, Harvey Fierstein. (One line of dialogue—“If you loved me, you’d vacuum–justified his subsequent Tony.) He was hired for the project before a composer had been picked. When Herman was selected, Fierstein was sent over to meet him. “Jerry came downstairs and threw his arms around me and he led me up and up and up to the top floor where there was a big room and a piano,” Fierstein recalled. “I said, ‘I can’t work like this. I lived in a basement.’” It didn’t take much to win him over. Their collaboration was sealed and cemented when Herman “sat down at the piano, and he sang a song that he told me was inspired by the opening scene of Torch Song Trilogy. The song was ‘[A Little More] Mascara,’ which then became the third song in La Cage aux Folles.

“Over all these years—over 40 years—Jerry and I remained close, close friends. We spoke all the time. We never had a disagreement over anything. He was the most wonderful collaborator you could image. He set the tone of my life, and I will be forever grateful for that.”

Jason Graae arrived on stage with his extra appendage—the oboe—explaining (lying), “I never met Jerry Herman, but, since I was going to be performing today, I thought it might be a really good career opportunity.” He did favor the audience with a song, “You I Like” from The Grand Tour, which he did in Los Angeles. Leslie Uggams did a gender-bent “I Am What I Am” powerfully, opening that song up to a whole spectrum of the disenfranchised. The first man to lift a baton to the Mame score, Don Pippin, conducted its overture for the memorial.

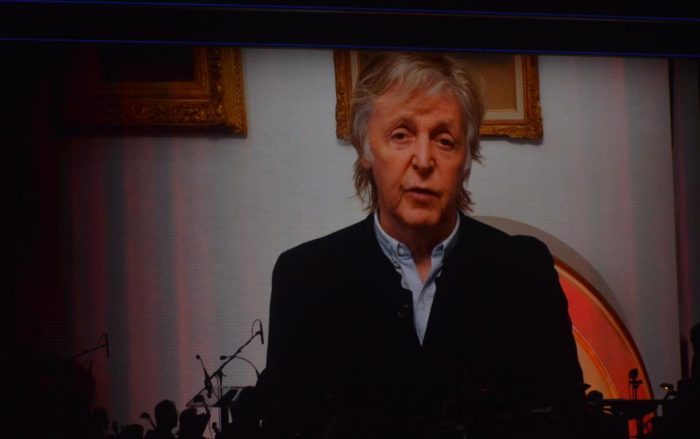

Sir Paul McCartney made a surprise appearance (via film) and spoke simply from the heart. “Your work puts you amongst the greats of musical theater and will live forever,” he said. “I want to thank you for letting me be a small part of your life. We’ll miss you, Jerry.”

The most emotional section of the memorial was watching Herman himself on film after his AIDS diagnosis introduce a song he had written in 1979 for Joel Grey to do in The Grand Tour. “I think you’ll understand why it has so much deeper meaning for me in 2003,” he said, launching into “I’ll be here tomorrow/Alive and well and thriving/I’ll be here tomorrow/It’s simply called surviving.”

The second most emotional moment: Bernadette Peters nailing the hopelessly hopeful and wrenching “Time Heals Everything,” as she did on Broadway 46 years ago.

Director Marc Bruni brought style and pacing to the proceedings—and in some cases dazzling visuals, like the procession of a dozen-plus Dollys that passed in review. All 19 performers gave the musical numbers (only the tip of the Herman iceberg) professional sheen and shine, but ultimately it was the non-pros who stole the show and told you more about Herman than you knew.

Terry Marler, Herman’s husband, co-produced the memorial with Feinstein and goddaughter Dorian. She thanked Marler for taking “such wonderful care of Jerry. Because of you, we had all those bonus years with Jerry.” That was seconded by Alice Borden, the other non-pro who laid claim to being “Jerry’s oldest friend.”

Since their friendship lasted 70 years, there were no challengers. She was eight and he was 19 when they met at summer camp. His parents ran the camp, and her mother was the music counsellor. “Every summer Jerry would put on one music show with the counsellors and the waiters, something I always looked forward to,” Borden remembered. “When I was ten, he did A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, and he needed a little girl to play Francie, and he picked me. Watching Jerry put these shows together was magical. He directed. He was a one-man orchestra playing the piano. He designed and painted the scenery and sets. He got the costumes. He sowed the costumes. He created a silk-screen poster. He was a one-man dynamo. He was always moving. During rehearsals, he would leap on and off stage with an energy I’d never seen before. He was inspiring and intoxicating, and I was a ten-year-old girl in love.”

A good ten years passed before he offered Borden another important role. “[Jerry] called me on a Friday and said, ‘Alice, David Merrick has asked me to write a few songs on spec for a musical version of The Matchmaker. Can you come over tomorrow and learn them?’ So I did. We spent two days learning four songs: ‘Put on Your Sunday Clothes,’ ‘I Put My Hand In,’ ‘Dancing’ and a ballad that was ultimately replaced by ‘Ribbons Down My Back.’ Monday morning we took the small elevator in the Sardi’s building up to the great Mr. Merrick’s office. Everything was in red, and he was an imposing presence. Jerry and I sang the four songs, and, when we were done, Mr. Merrick sat up and said, ‘Kid, the show is yours!’ We all shook hands, and Jerry and I calmly got back into the small elevator. We barely spoke on the way down, but, when we walked outside onto 44th Street we were crazy. People were looking at us, jumping up and down with excitement. And then we went for ice cream, chocolate of course. The rest is history.”

That history was duly noted by Dorian. “Jerry’s work has often been compared to Irving Berlin’s in that they both had the gift of writing songs that made you want to sing as you left the theater. Jerry expressed character and plot, essential to the integration of the musical. By fundamentally respecting the underlying source material, he was able to distill the essence of the human condition. Then he took it one step further: finding language that ran deeper than words. That is why, in every moment of every day, someone around the world is on a stage singing a Jerry Herman song.”

Lee Roy Reams wrapped the afternoon up with a rousing rendition of “The Best of Times,” ending the memorial as it began on a celebratory note.

When asked once point blank what his favorite lyric was, Herman cited one from “I Am What I Am” without any kind of hesitation: “I don’t want praise, I don’t want pity/I bang my own drum/Some think it’s noise, I think it’s pretty.” You’d be hard-pressed to find a better definition of Jerry Herman’s art.

Needless to add, the audience left the theater humming the legacy . . .

Photos: Maryann Lopinto