By Samuel L. Leiter . . .

EXTENDED THRU OCT. 15 . . .

Job, a two-hander by Max Wolf Friedlich at the SoHo Playhouse, begins like a thriller, with a young woman pointing a pistol across the small stage at a much older man. Several unclear moments pass during which things happen and then are reset so they can be viewed otherwise before the frightened man, Loyd [sic] (New York theater favorite Peter Friedman, recently of HBO’s “Succession”), persuades the disturbed woman, Jane (Sidney Lemmon, in her Off-Broadway debut), to put the weapon aside. About 70 minutes later, it reappears shortly before the play ends.

In between, Loyd, a San Francisco therapist, engages Jane, initially embarrassed by her threatening behavior, in a therapy-like session during which he seeks to calm her down and explore her troubled mind; the very smart Jane, in turn, skeptical about therapeutic practice, sometimes turns the tables and gives him the third degree. Her goal is to have him sign papers agreeing she’s psychologically capable of returning to the unusual internet-related job she professes to love and from which she was released after having a public breakdown. We learn only late in the action of her job’s demanding responsibilities, and its precise relationship to the theme of the internet’s dangers. (Job, by the way, doesn’t seem intended as a heteronym for the Biblical personage, although I wouldn’t be surprised if someone finds Friedlich did have irony in mind when devising this title.)

Given Jane’s stressed-out state of mind—there are allusions to Xanax, self-harm, and panic attacks—and Loyd’s vulnerability in view of what is really a hostage situation, the wide-ranging, talky session (including topics like racism, technology, gentrification, hippiedom, abortion, etc.) is fraught with tension, intellectual and psychological. Its hold over us is maintained by the note-taking shrink’s determination to discuss Jane’s issues, and hers to carry out a hidden agenda.

Eventually, we learn that the job to which Jane is anxious to return concerns the internet’s most harmful corners. SPOILER ALERT: Her job, called either “user care” or “content moderation,” is to monitor and erase images of the worst excesses of human behavior; the horrible things she sees are traumatizing yet clearly in need of someone like her to eradicate them. (One wonders who’s minding the store when she’s not around, like now.)

Friedlich’s play, then, questions the damage done by our phones and computers to our mental state, if not to the social fabric itself. What passes for a session between a troubled woman and a probing therapist has a valid thematic purpose but can’t avoid culminating in an implausible conclusion of the butler did it variety, a device that seems the inspiration for the entire enterprise.

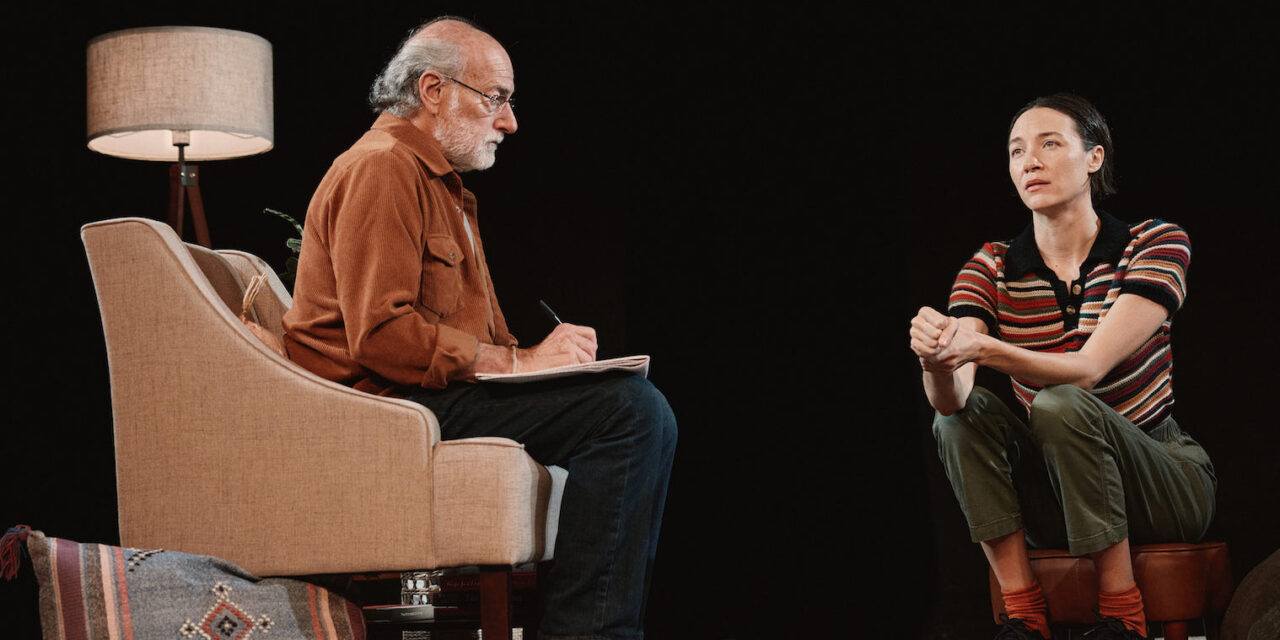

Regardless of its melodramatics, Job—which can’t avoid being reminiscent of the Gabriel Byrne series, “In Treatment”—provides two fine actors with lots of histrionic opportunities. Scott Penner’s low-budget scenic design is limited to a pair of facing beige chairs, supplemented by a few decorative items, nothing more being required to create the sense of a therapist’s office. Michael Herwitz’s direction keeps the drama simmering, allowing the actors to perform in a rapid-fire, naturalistic, conversational style underlined, because of Jane’s potential volatility, by a sense of danger. Now and then, the realistic tone is blurred when colored lights—designed by Mextly Couzin—pop on and off to the accompaniment of amplified computer clicks (sound is by Jesse Char and Maxwell Neely-Cohen) as if to alert us to something about Loyd not being quite right. Now and then, other odd, disconcerting offstage sounds are heard as well.

Friedman, dressed casually in a rust-colored shirt-jacket and jeans (Michelle J. Li did the costumes), is pitch perfect as the cautious but professionally inquisitive therapist, struggling to keep his calm, subdue his fear, and resolve the situation without doing anything foolish. Lemmon (granddaughter of the late Jack Lemmon), her hair in a boyish cut, her lanky frame garbed in a decidedly unprepossessing ensemble of baggy pants and striped, sleeveless jersey, offers a sensitive, intelligent performance as the quirky analysand; speaking with hyped-up rapidity, sometimes almost mumbling, she keeps us wondering just how unbalanced she is, and why. The reasons may not be convincing, but she’s fully invested in believing them. Each actor also succeeds in sparking laughs with their occasionally ironic lines.

A surprisingly packed house filled the funky Soho Playhouse at the matinee I attended. The auditorium’s rake being very slight, I had to keep stretching my neck to see beyond the big head of the man—a well-known critic—in front of me, which, in turn, surely irritated the person behind me. The crowd was doubtlessly drawn more by Friedman’s presence than by his talented young costar. Both do a better job of maintaining interest in Job than the contrived play itself; for that reason alone, a trip to Vandam Street will prove rewarding enough.

Job. Through October 8 at SoHo Playhouse (15 Vandam Street, between Sixth Avenue and Varick Street). www.sohoplayhouse.com

Photos: Emilio Madrid