By Samuel L. Leiter . . .

Tripping on Life is a one-woman play now running at Theatre Row, written by and starring Lin Shaye. I admit to not knowing who this septuagenarian character actress was before reading her program bio; however, horror film buffs may recognize her because, during a prolific career in which she’s acted in a couple of hundred films, she carved out a niche as a “scream queen” in such presumably chilling efforts as the Insidious franchise. Given the abundance (and variety) of her screen roles, one might be forgiven for thinking that, if she wanted to present a memoir-based solo performance, she could have drawn on this vast, surely fascinating experience, with particular reference to her work in movies like Alone in the Dark (1982), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), Critters (1986), 2001 Maniacs (2005), Ouija (2014), and so many, many more, even if you—like me—had never seen (or even heard of) most.

But, no, Shaye never mentions her film work—perhaps she assumes everyone is familiar with it—but opts instead to focus on her memories of 1968, when the actress, then in her early 20s, was a drug-addled hippie in love with an even more radically free soul, a handsome hunk named Marshall whom she had met at the University of Michigan.

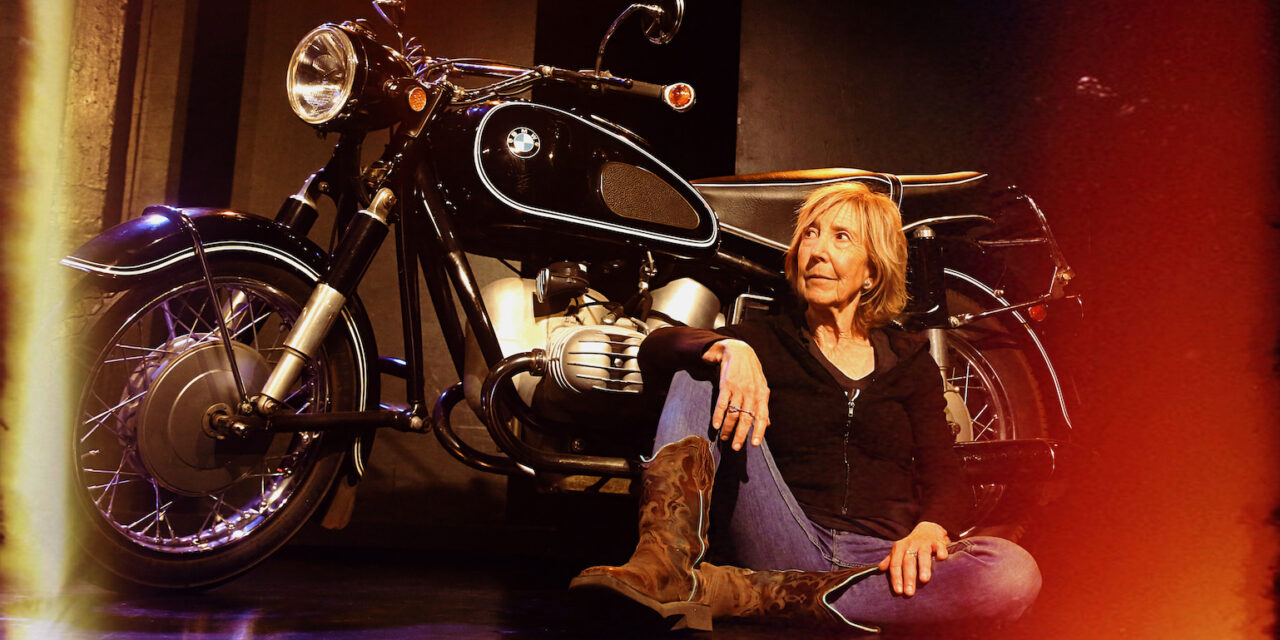

The result is a banal, self-indulgent, exaggerated tale of her marriage to Marshall; their move to abject, pot-imbued conditions in San Francisco; their encounter with two goofy cops while speeding and stoned, along the California coast near Big Sur, she in the saddle of a BMW motorcycle shakily secured to the rear of a noisy flatbed; the reaction of her middle-class Michigan parents—and her bullying brother—to her and Marshall’s flower child wedding (he wore only a thong) and lifestyle . . . and so on. Little of it is particularly interesting, much less convincing, no matter how enthusiastically delivered.

For all its futile attempts to sound humorously hip, with dozens of F-bombs, dudes, drug references, and exaggerated examples of the hippie syndrome (including young men who answer the door totally nude, even in a state of arousal), the narrative struggles to get beyond the sleaziness and surprising cluelessness of its characters, including Shaye’s own, or to define them in more than one dimension. Written in the manner of a film script, the story is partly told in reverse order. Eventually we get to what clearly inspired its creation, Marshall’s sad fate, followed by a coda about how the couple first met that’s intended to be a charming surprise, though it does nothing to make up for what’s preceded it.

The hour-long enterprise, stodgily directed by Robert Galinsky, is enacted on a mostly bare, black-walled stage, with a few small pieces of furniture and a classic BMW motorcycle (like the one mentioned in the play); since it remains visible throughout, but is neither touched nor mounted, its presence is both unnecessary and distracting. Joshua White and Marian Saunders illuminate it all efficiently, with an increasingly boring, off and on background of presumably psychedelic video images (credited to Joshua Light Show) of liquid colors spreading this way and that. Video images of California hippie life, not to mention photos of Shaye and Marshall—like those printed in the program—would have been far more pertinent. Lee Landry’s sound design mixes original music with what appear to be period tunes; perhaps it’s a rights question, but the score never comes close to capturing anything like the indelible tone of 1968’s music, which would have gone a long way to supporting Shaye’s tale.

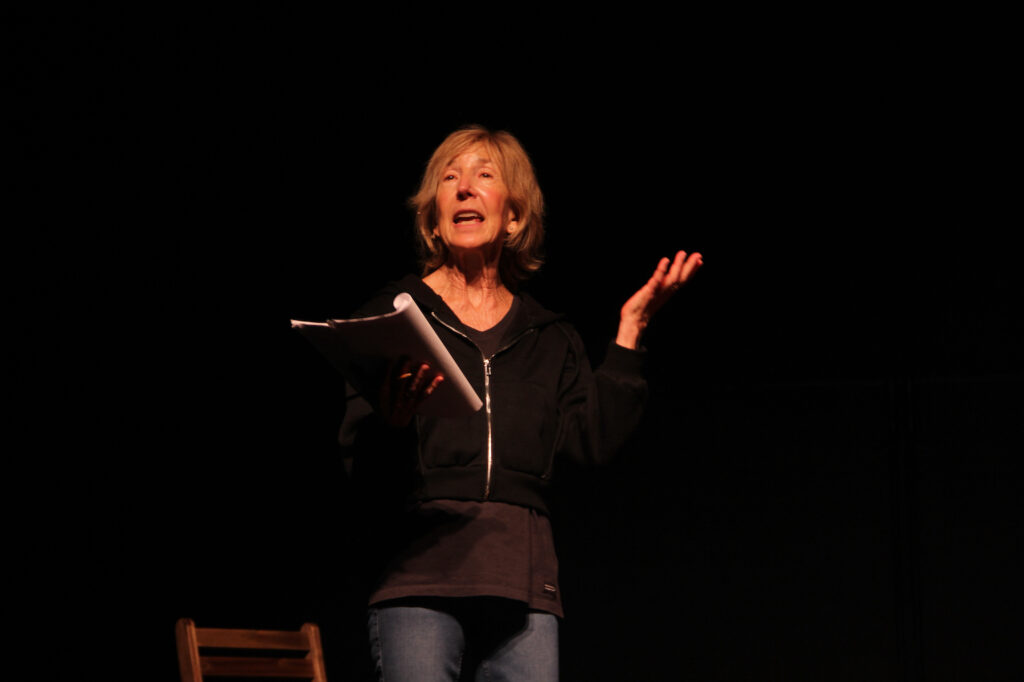

Shaye—her blonde hair in shaggy pageboy mode, her trim figure wrapped in a close-fitting, casual ensemble of black sweat pants and top—has the voice and aura of an experienced actress. Still, she lacks the versatility and charm needed to play the multiple characters she portrays with little more than awkwardly stereotypical voices and gestures.

Worse, however, for whatever reason, Shaye—at the preview I attended—chose to throw the show away by HOLDING THE SCRIPT (AND A PENCIL) IN HER HAND THROUGHOUT. Given that this is advertised as an “award-winning” play previously seen elsewhere, one wonders what award that might be and why she performed it without fully memorizing its lines, lines she herself wrote! Normally when this occurs, an explanatory comment is provided as a courtesy. Not so here. Watching an actress depend—as Shaye clearly does—on a handheld script robs her of the physical expressiveness two hands provide, while also being annoyingly off-putting.

It’s also insulting to an audience that (unlike we lucky critics) has paid good money for the privilege of attending. Tripping on Life, I’m afraid, succeeds in tripping not so much on life, but on itself.

Tripping on Life. Through October 8 at Theatre Row (410 West 42nd Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues).One hour, no intermission. www.theatrerow.org

Photos: Robert Galinsky