Theater Review by Samuel L. Leiter . . . .

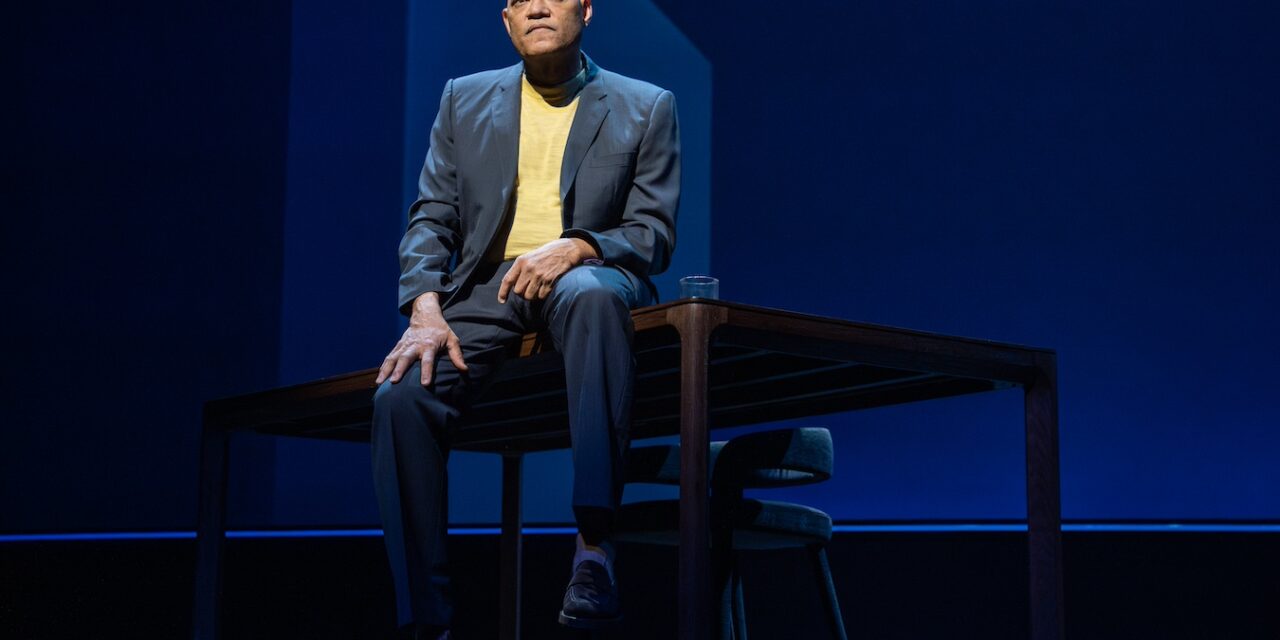

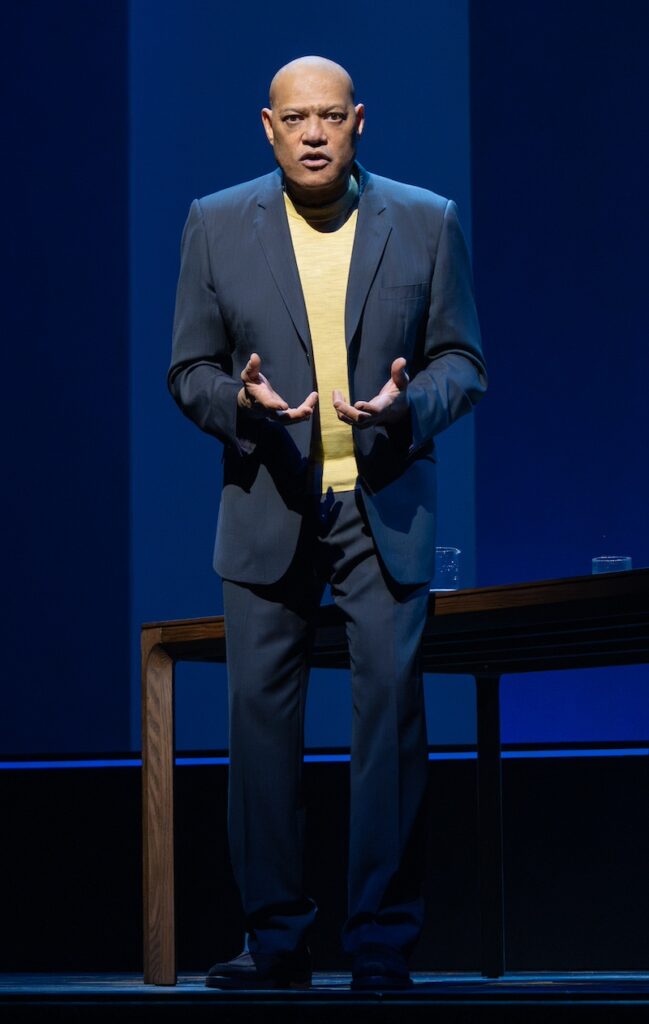

Laurence Fishburne has been a TV, film, and TV presence for just about 50 of his vigorous 62 years. During that half-century of thespian activity, he’s accumulated acting chops that have gained him multiple awards and honors. He puts those skills on glowing display in his new histrionically distinguished but dramaturgically overwrought new play, Like They Do in the Movies, a one-person, multi-character show of his own authorship.

The show is at the spanking new—opened in September 2023—Perelman Performing Arts Center (NYC PAC), the large, grayish-white cube located next to the Freedom Tower, across from where the Twin Towers stood, diagonally opposite the externally striking, internally sterile shopping mall and transit hub called the Oculus. This was my first visit to the NYC PAC, whose presence adds a prestige performance venue to Lower Manhattan, so I was as interested in the space as in the production. Each combines impressive features with problematic ones.

For all its up-to-date architectural features, the theater’s lobby area—which includes a fashionable restaurant called The Metropolitan—is coldly bleak, more functional than welcoming (although an army of helpful personnel is on hand to assist the public). The lobby area restroom—behind the restaurant—requires a hike to a large room in which only three sizable, gender-neutral rooms are provided.

The theater for Like They Do in the Movies is on an upper floor, accessible by stairs or elevator (I shared the ride with the great actress-writer-professor Anna Deavere Smith), but, again, the walk to the restrooms is a distant trudge and down a flight. The theater’s surprisingly bland interior contains a barely raked floor, causing sightline problems if anyone with a head sits in front of you (at least that was my situation in row H), even with a relatively high stage. And the seats, though upholstered in red velvet, are flat, hard, and uncomfortable, more like dining room chairs than theater seats.

Fishburne’s play—given a reading last summer by New York Stage and Film—is an anthology of tales, mingling truth and fiction, although so well acted it’s hard to say which is which. Most likely, the material that bookends the show, memoir-ready stories of the actor’s birth, upbringing (in Augusta, Georgia, and Brooklyn), and family, focused largely on his estranged parents, is authentically autobiographical.

Sandwiched between those bookends are five unrelated stories, each presented by its own distinctively garrulous narrator, at least one each white and black, and the others, as far as I could tell from the monologues’ machine-gun speed (no script was available), of indeterminate race.

The actor’s stories of his colorfully eccentric father, an imposing good-time Charlie, and promiscuous mother, Hattie Bell Crawford, are engrossing enough for an evening of their own. His mother was a whip-smart, attractive, promiscuous woman who eventually was diagnosed with Narcissistic Personality Disorder, Type 2 or NPD; she also had pedophiliac inclinations, which Fishburne did not realize until his maturity. Even her telling her inquisitive son who his biological father was turned out to be questionable, leading to a DNA quest to learn his identity.

Despite his ultimate rejection of Hattie, Fishburne didn’t completely turn his back on her. In fact, toward the end of her life, her dementia forced him to place her in a facility, for which he footed the bills. In a scene toward the end, he even shares the stage with his mother, playing both her and himself, switching back and forth with lightning speed, changing his face and voice instantaneously.

He’s quite a master of this technique, which he uses for all his stories, providing a remarkable display of technical virtuosity as he ably distinguishes one person from another, male and female, through voice, body, gesture, and dialect without resorting to prop or costume changes within any specific narrative. He tells his personal stories as himself, speaking directly to us (ad libbing when latecomers arrive), and switching to someone else when the narrative demands it. The raconteurs who make up his chief dramatis personae are people he’s presumably met who are recounting their stories to him, Laurence Fishburne, the Hollywood star.

The five internal stories are delivered by a barfly named Fitzpatrick, who tells a story of something that happened one night after he finished an all-night shift of heavy labor at the Daily News; a lawyer recounting his harrowing experience during Hurricane Katrina; a peace officer, presumably on a movie set, assigned to protect the star from invasive fans; a jiving street hustler and druggy whose hustle is washing cars; and the elegant, American, male equivalent of a brothel proprietor (he rejects the term “pimp”) whom Fishburne meets in Australia.

Fishburne’s writing captures with uncanny accuracy the rhythms, accents, vocabulary, sentence structure, and thinking of his widely varied, unerringly articulate main and minor characters (the latter including mobster John Gotti); his acting is equally believable, even when the burly actor sashays across the stage in sequined femininity.

Disappointingly, regardless of the title, none of these verbose monologues has anything to do with what they do in the movies, although Fishburne surely can unpack countless stories of his filmmaking experiences. It’s certainly what I was hoping for when I attended.

However, no one, not even director Leonard Foglia (who staged Fishburne’s acclaimed one-man show as Thurgood Marshall), has helped the star shape and trim his monologues to reasonable lengths. Each one outstays its welcome, diminishing its impact. They become shaggy dog stories with generally shaggy, ineffective endings. Apart, perhaps, from self-indulgence, it’s hard to justify a one-man play with only the barest suggestion of thematic continuity having a run time of two hours and 20 minutes—a length we typically associate with subjects of epic proportions. If 45 minutes were scissored, or even one of the episodes dropped, and the evening were better shaped, Like They Do in the Movies would be radically improved.

Neil Patel’s set is little more than tables and chairs, well-lit by Tyler Micoleau and backed by a screen reflecting Elaine J. McCarthy’s projections, including abstract effects as well as stills of locales and people (like Fishburne’s family). Those images presenting the admirable array of Fishburne films get oohs and aahs. Justin Ellington contributes an effective sound design, much of it composed of hip musical choices (lots of jazz, for instance).

No one, however, is credited with Fishburne’s costumes, a wise choice considering what he wears. He looks fine in a blue suit and yellow sweater, and half-fine when he wears a tan turtleneck sweater and some kind of strange, baggy pants. But he also appears in several odd, heavily cowled concoctions, one blue and sequined, another black and gray, and another silken and copper-toned. These crosses between robes and caftans more closely resemble the flying suits you see on Tik Tok worn by people jumping off cliffs or out of planes.

Without a cohesive script to serve Fishburne’s admirable acting talents, Like They Do in the Movies will continue to remain earthbound.

Like They Do in the Movies. Through March 31 at the Perelman Arts Center/PAC NYC (251 Fulton Street, Lower Manhattan). www.pacnyc.org

Photos: Joan Marcus