By Samuel L. Leiter

I just saw a video on Facebook that cites all the plagues and wars that failed to kill the theater. But it left out one moment, neither a plague nor a war, which nearly destroyed, if not the theater, then its usually throbbing commercial heart, the neighborhood known as Times Square. That, of course, is where the Broadway theater has lived since the early twentieth century, after slowly moving uptown from its beginnings in what is now the financial district.

For those who may not know of or remember this moment in our very recent history when Broadway bounced back, like the Fabulous Invalid it is, from near oblivion, here are a couple of pages from the first chapter of my book, Ten Seasons: New York Theater in the Seventies (Greenwood Press, 1986). Except for one tiny correction, they are just as they were when originally published. If you ever watched HBO’s “The Deuce,” about Forty-second Street in the seventies, you may have an inkling of where this is going.

The New York theater may never have battled quite as formidable a foe as it’s up against right now, but the story of what happened in the seventies proves once more that theater fills a powerful human need that will not be denied. It should give us hope that theater will survive this devastating attack and come back stronger than ever.

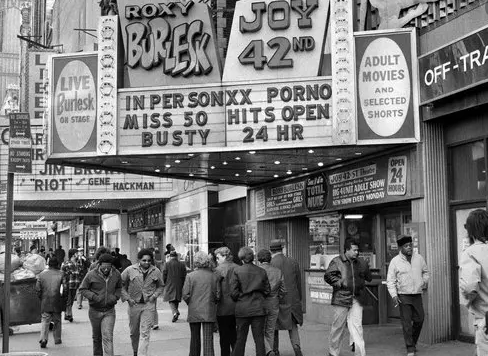

At the onset of the 1970s, the Broadway theater district was rapidly sliding into the mire of despair. Broadway, wrote New York Times critic Walter Kerr, was like a ghost town the streets of which were so silent “you could put your ear to the ground and hear only the subway.” Theaters were empty and marquees were dark. When, in 1993, a national energy crisis forced theater landlords to cut back their marquee and display case lighting by 25 percent, a palpable cloud of gloom pervaded the entire neighborhood.

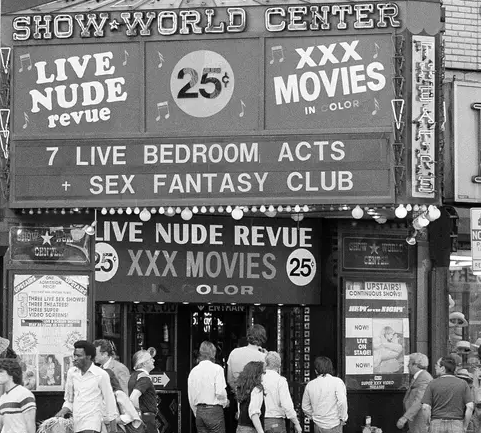

Times Square was the blighted symbol of the putrid mess into which the Broadway theater district was evolving. Garbage was piled high on Broadway’s once fabled streets; pornography, prostitution, and drugs were easily available on sidewalks and in doorways; and muggings were commonplace. At one point in 1970 seven members of the Lyceum Theater production of Borstal Boy were mugged within a three-week period, six right near the old Forty-fifth Street playhouse. Well-known actress Barbara Barrie never went anywhere without her trusty umbrella with which to bash would-be assailants over the head. Brazen thieves came right up to the box office to snatch the cash out of ticket-buying hands.

Broadway’s leading powers sought every means to stem the wave of crime and to control the spread of smut, but their efforts proved as futile as spitting into the wind. More police, better garbage pickups, improved street lighting, and all sorts of zoning ordinances and licensing laws were proposed and, often, put into effect. Producer Alexander H. Cohen, a major force in the attempt to clean up what theatrical publisher Leo H. Shull called “Slime Square,” even asked for a special committee to approve all new businesses planning to open up the district. For all its questionable overtones, Cohen’s was a poignant plea in the wilderness for some sort of government intervention to prevent Broadway from sinking in the muck of shoddiness surrounding it.

Actors demonstrated, rallied, and signed petitions to make the area safe and respectable once more. In 1972, after being propositioned by a teenage girl and hearing of another actress who was urinated on by a stage door wino, actress Joan Hackett circulated a petition asking the city to set up a separate red-light district in which the sex merchants could ply their trade. In 1975, a crew of 200 Broadway celebrities manned brooms in a massive street-cleaning demonstration to point up the area’s deterioration. Two years later, the casts of twenty-five Broadway shows, many in full costume, took part in a massive anti-pornography rally attended by about 8,000 people. Yet, despite these and other efforts, and the periodic “cosmetic corrections,” as the New York Times liked to call them, Times Square’s smut remained consistently visible. A New York Times editorial observed in 1977, “The city appears unable to protect its theatergoers from the psychic shocks of drama’s present environs.”

Some signs of improvement were beginning to appear by the end of the decade. Two Broadway theaters had been reclaimed from their fate as movie grind houses, and the promise was that more conversions would come as new productions proliferated and the possibility of a theater shortage grew. Theatre Row, a group of Off- and Off-Off-Broadway playhouses, successfully abolished the porno elements from Forty-second Street west of Ninth Avenue. Across the street from Theatre Row was the new Manhattan Plaza, an apartment complex for show people. Big money was being invested in area hotels, housing, and business, with various plans in the air for developing the district as an enormous entertainment and cultural center.

Times Square continued to present a sleazy, dangerous face to the public through the end of the decade, but the Broadway theater by then had experienced a great surge of commercial popularity; in contrast to the early part of the period, large crowds of eager playgoers were turning out and keeping local theaters open. The recently moribund Broadway theater had made an economic comeback that was nothing short of astounding.

(to be continued)