Theater Review by Carol Rocamora . . . .

Context. That is what struck me as the value of Sunset Baby, Dominique Morisseau’s gem of a play, now being given a mighty revival at the Signature Theatre. There is its context in recent Black American history; there is its context in Morisseau’s rich and important oeuvre; and then there is its context in a theater’s commitment to support the works of American playwrights.

Even as we are still riding the crest of the wave of the Black Lives Matter movement, along comes a revival that takes us back to an earlier and equally powerful period in Black American history, providing us with precious perspective. Written in 2012, Morisseau sets her play in 2000, featuring a father-and-daughter relationship that has been indelibly marked by the Black Power movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s when its leaders dominated the headlines, along with the Black Panther Party and Black Liberation Army. Indeed, you can see photos of Angela Davis, Assata Shakur, Afeni Shakur, and others in the lobby as you enter the Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre space.

In Sunset Baby, Morisseau has made a powerful dramatic choice. She has created a character named Kenyatta (Russell Hornsby), a fictitious revolutionary leader (based on one that could have come from the 1960s-70s) who was imprisoned for an attempted armored-truck heist “to steal capitalist dollars in the name of Third World democracy.” Kenyatta reappears decades later to confront his daughter (who was five at the time of his imprisonment and hasn’t seen him since) with a request that provokes an explosive dramatic conflict between the two.

Kenyatta’s daughter was named “Nina” by her father (after Nina Simone, the famed singer and political activist of the period). But Nina (a magnetic Moses Ingram) is deeply conflicted by this legacy. Her activist mother Ashanti X, heartbroken by the imprisonment of her husband, descended into drug addiction and a subsequent early death. When we meet Nina, she’s roughly thirty, living in a shabby one-room apartment in New York City, and still in search of her identity following her traumatic childhood. Her dream is to escape her current life-in-limbo with the money that she and her boyfriend Damon (J. Alphonse Nicholson) hope to gain in a series of street scams, selling drugs and then robbing the buyers.

Morisseau has created three rich and complex characters who elicit from us a range of powerful emotions. Stalking her tiny apartment in her mini dress, pulling on her thigh-high shiny blue boots, donning her red wig and pink floor-length fur-collared coat, Nina (as played by an electrifying Ingram) is a charismatic figure. Dressed for a life of crime (by designer Emilio Sosa), Nina is a clash of conflicting passions ranging from anger to profound sorrow, as she mourns her mother’s death while trying to find a life for herself in a new era. Her confrontation scenes with her father unleash a flood of rage as she discovers the purpose of their reunion. Kenyatta, it is revealed, is desperate to have a stash of letters that Nina’s mother wrote to him while he was in prison. They are Nina’s sole inheritance and of historic value—and she is loath to part with them, especially by giving them to a father whom she feels never loved her and abandoned her mother. When Nina realizes, however, that she can demand money from her father in return for the letters, she agrees to meet Kenyetta again . . . and negotiate a price of ten thousand dollars to finance her flight with Damon.

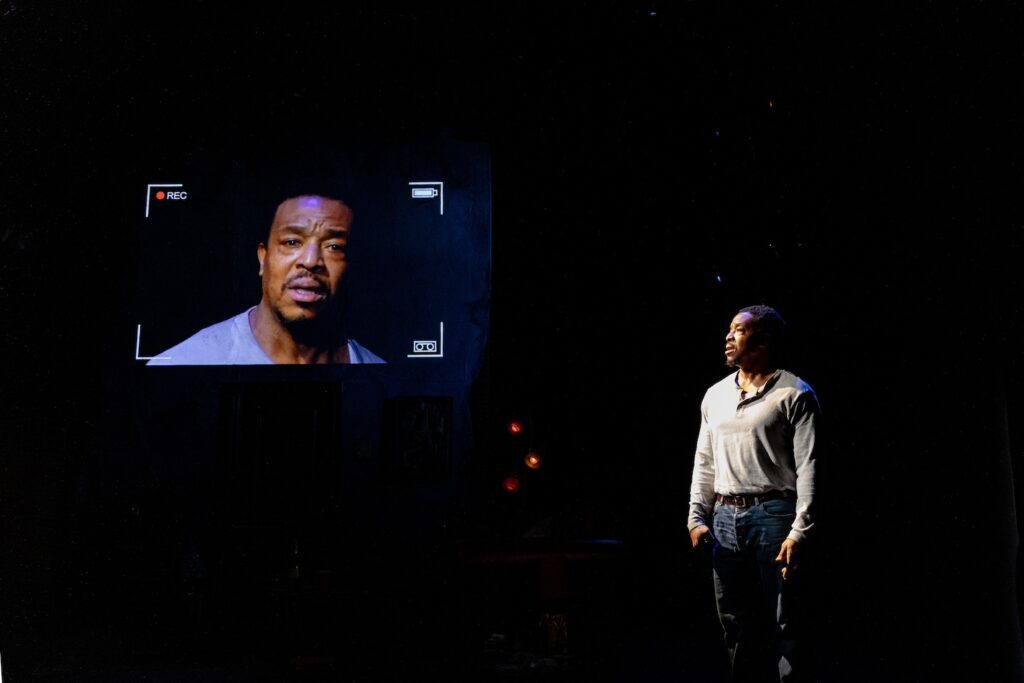

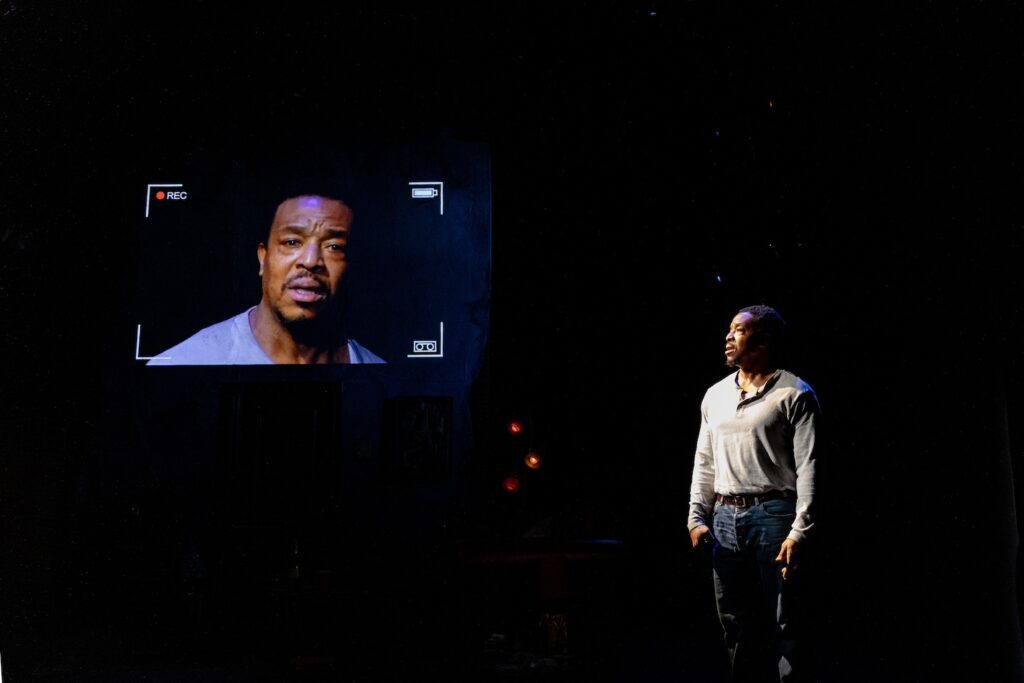

Meanwhile, Kenyatta finds it almost impossible to articulate his feelings for his daughter, let alone offer an apology for his desertion that Nina requires. His only mode of expression comes in the form of video messages that are projected on the upstage wall of Nina’s apartment, punctuating scenes between the characters. Powerful and eloquent, they are speeches dominated by political theory rather than emotion. “This is all I know, Nina,” he says in one of the videos. “Speaking. Writing. Ideas. Activism. Justice. Meditation. Pondering.” As Kenyatta, Hornsby finally wins our empathy in his valiant, sincere struggle to show his daughter how much he loves her.

As Damon, Nina’s partner in crime, J. Alphonse Nicholson engages us with his contradictory mixture of charm, manipulation, and ultimate dependency. Steve H. Broadnax III has directed this powerful, virtuosic trio with clarity and heart. Punctuating the scenes with Simone’s songs, the play conjures up several eras in that shabby one-room apartment (designed by Wilson Chin): the 1960s and 2000, with a forecast of today. Speaking of the tragic victims of the police shootings that spurred the Black Lives Matter movement of 2013 and thereafter, Morisseau says in the program notes, “It almost feels like their deaths could be preventable, in a time-traveling sort of way.”

Author of the celebrated Detroit Project (a three-play cycle featuring Skeleton Crew, Paradise Blue, and Detroit ’67) and other timely plays like Confederates and Pipeline, Morisseau continues to create an important dramatic oeuvre in the American theater. “An artist’s duty is to reflect the times,” Nina Simone once said. With Sunset Baby, Morisseau has accomplished that—and more. She has delivered both a powerful political play and a family play as well—one that, as the Signature production proves, is a lasting one. As Morisseau says: “Sunset Baby is about activism and the traumas that come with having spoken out—the backlash and bullying and intimidation, and even imprisonment, that come from attempting to have a cause you believe in. How does that rebound across generations? In asking this question, it also becomes a play, in its purest essence, about parenting.”

Sunset Baby. Through March 10 at the Signature Theatre Center (480 West 42nd Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues). www.signaturetheatre.org

Photos Marc J. Franklin