by Michael Bracken

It’s timely, all right, too timely – but not surprisingly so. With another senseless shooting spree occurring every few months or weeks – seems like days – a fictional drama enmeshed in mass murder is bound to find itself a stone’s throw – temporally speaking – from the Real McCoy. And so it is with Lindsey Ferrentino’s This Flat Earth, which began previews at Playwrights Horizons Mainstage Theater in early March, on the heels of the Parkland tragedy.

Yet Ferrentino’s drama is not about a mass murder, at least not directly. It’s more about the collateral damage that follows in a school massacre’s wake. The killings are woven into every fiber of Ferrentino’s slyly affecting work. But, with one exception, the killings function more as subtext than subject.

This is especially true for middle schooler Julie (Ella Kennedy Davis), who, at thirteen, navigates the fine line between childhood and adulthood without much finesse but with all the determination she can muster. Circumstances have eliminated adolescence as an option. Her growing pains are exacerbated by her place in the socio-economic spectrum. Her schoolmates come from the lower, tonier part of town, while she and her dad live higher up the hill, lower on the moneyed totem pole.

Like Julie, her classmate, Zander (Ian Saint-Germain), is more focused on growing up than mourning people he barely knew, even if they were from his school. He stretches his arm to put it around Julie but chickens out at the last second. Later, Julie is more amenable to an ice-breaking kiss, but once again he loses his nerve.

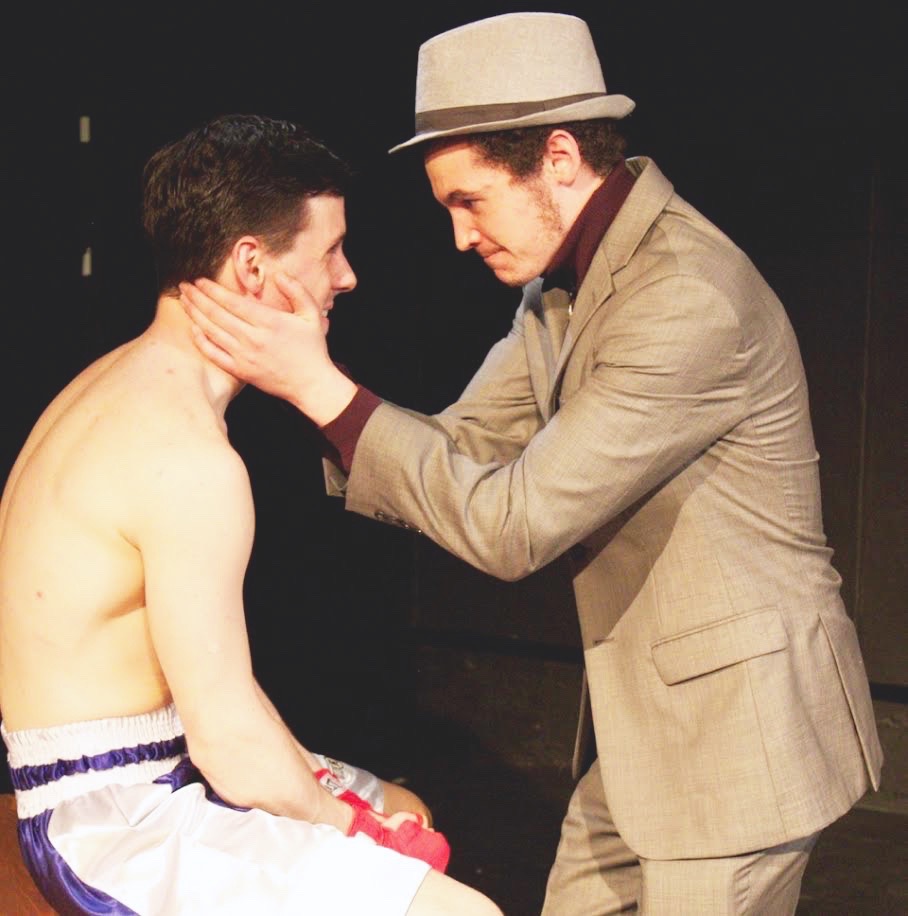

Julie’s father, Dan (Lucas Papaelias), is helping Lisa (Cassie Beck) move some boxes with plenty of innocent flirtation on both sides. (Her husband’s alive; his wife is dead.) Lisa, often referred to as Noelle’s mom, is most obviously affected by the shootings: Noelle was one of the victims.

The play begins with battle lines clearly drawn. It’s kids (Julie and Zander) vs. adults (Dan and Lisa), but the adults don’t know that. The kids are holed up in Julie’s room, with Julie impatiently wondering to whom her father’s talking and then downright angry when she figures it out. When Zander leaves, and Julie reveals herself, she’s horrified when Noelle’s mom invites her dad and her over for dinner. “Why would I go to your house again?” she asks, rudely but with complete candor.

But it’s money, not age, that fuels the play’s central conflict. It seems that Dan used his work address to get Julie into the school at the bottom of the hill, which he perceived as better, and this becomes known in the attention to detail following the massacre.

Two other characters feature in the story. The first is “the woman upstairs,” Cloris (Lynda Gravátt). Dane Laffrey’s wonderfully simple set consists of two rooms of two apartments, one on top of the other. As the play begins, Julie and Dan are each in one room of the lower apartment, while an eightyish woman is in one of the upper rooms. At first all she does is knit and put records on the stereo, but eventually she’s more integrated into Julie’s life.

The records she plays are not really records, however. There’s a live cellist (Christine H. Kim) seated next to the audience who plays whenever Cloris turns on the stereo. Cloris tells Julie she used to play the cello and starts to give Julie lessons. We also learn that Noelle played the cello and that the cello approximates the size and weight of a human being. Somehow the live cello music enhances the work with a mystical patina.

Rebecca Taichman’s direction is affectionately gentle – how could she not feel affection for Ferrentino’s beautiful script? Director and writer are of one mind and present a story that resonates.

The cast is uniformly marvelous. Davis shines in petulant innocence, while Saint-Germain is only slightly more mature. Papaelias juggles single parenthood with economic struggles and love for his daughter. Beck’s Lisa is far more chipper than a mother who lost her child should be, using cheerfulness as a very effective shield from the sorrow underneath.

Through April 29th at the Playwrights Horizons Mainstage Theater (416 West 42nd Street). www.phnyc.org . Ninety minutes with no intermission.